Revisiting the big hair and plastic grass

The 1970s are rarely (OK, never) described as a golden era in baseball. The sport certainly experienced its share of colorful moments and flashy personalities during the decade, but Disco Demolition Night and Mark Fidrych are not discussed in the same hushed tones as Bobby Thomson's Shot Heard Round the World or the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers.

Notwithstanding Hank Aaron's assault on Babe Ruth's career home run record and Lou Brock's new single-season mark for steals (118 in 1974), the decade was short on gaudy statistics, too.

"Nobody hit .400 in a season, or won 30 or more games. Only one player -- George Foster in 1977 -- managed to hit more than 50 home runs in a season," Dan Epstein writes in "Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride through Baseball and America in the Swinging '70s." "But in those categories that continue to defy statisticians -- weirdness, hairiness, overall funkiness, and sheer amusement -- the 1970s still tower over every other decade before or since."

You don't have to remember where you were when Dock Ellis pitched a no-hitter on LSD to appreciate the unique confluence of sociological elements that came together during that era of baseball, when "the rebellious, anti-authoritarian spirit that had been so palpable on college campuses since the late 1960s seemed to have finally infected the sport," writes Epstein, 44, a music journalist by trade who's written for Rolling Stone and is the managing editor of Shockhound.com, a music website. "If the integration of baseball in the 1940s and '50s sparked changes in American culture, then the '70s was the decade where the changes in American culture turned back around and impacted baseball. Even during the turbulent 1960s, baseball players looked, spoke, and played as conservatively as their counterparts in decades past."

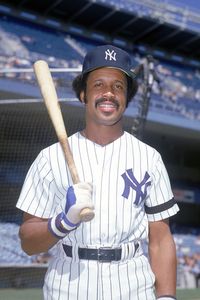

Oscar Gamble in 1975, however, looked like he'd been dropped off by the mothership of Parliament-Funkadelic.

The big hair afro bespoke rebellion and flair, a personal style. Players, like society at large, were taking more liberty in flying their freak flags. In turn, they began rebelling against the decades-old system that saw owners dominating the game and its profits.

Unhappy with their pension program, players briefly went on strike for the first time in the sport's history in 1972. When fans expressed their displeasure with this development by staying away from the ballparks, American League owners tried to reinvigorate fan interest (as well as game scoring) by adopting the designated hitter the following season. For the most part, though, it was an era dominated by pitching, defense and speed, when some of the game's best teams -- the Reds, Pirates and Royals -- played in "cookie-cutter" stadiums on the ubiquitous AstroTurf, "a low-maintenance plastic lawn -- laid over a concrete base -- that could be quickly vacuumed and dried after a rainstorm."

"In a decade bookended by '2001: A Space Odyssey' and 'The Empire Strikes Back,' it was somehow appropriate that over half of major league baseball's teams played their home games in stadiums that resembled spaceships," Epstein writes. "In the cultural shorthand of the American 1960s and '70s, space signified the future, the future represented progress, and the civic architecture of the day did its best to reflect this futuristic impulse."

The future wasn't the only thing driving the impulses of people within baseball. So was money. With the advent of free agency in 1976, players were able to sell their services to the highest bidder. Owners, in turn, needed to generate money to attract and pay the first generation of millionaire ballplayers. The best way to do that was by filling the stands with fans. And that meant sacrificing some dignity, well, so be it.

The Ted Turner-owned Braves were a representative example.

"Braves fans in the late '70s bore witness to (and often participated in) such ridiculous promotions as bathtub races, tightrope-walking demonstrations, 'cow pie'-throwing competitions, blanket- and mattress-stacking competitions. … Turner himself often joined in the fun, donning riding silks for ostrich and camel races against local sportswriters, and besting Phillies reliever Tug McGraw in a contest to see who could push a baseball around the bases the quickest using only his nose."

Shame? What shame?

The Braves even helped popularize the wet T-shirt contest, staging one on the field after a May 1977 game at Fulton County Stadium. The Braves' publicity director later said, "We didn't know what we were inventing. Our 'college night committee' suggested the ridiculous idea. They wanted it topless; I suggested the T-shirt. They countered with the idea of adding water. I assured Ted [Turner] we would get lots of publicity and lots of tickets. I was certain someone would step in and stop us before the event ever took place. No one did."

Such was the spirit of the '70s, a loosey-goosey era succeeded by the Reagan years and its conservative zeitgeist. Baseball continued to change with the times in the 1980s.

"The exuberant experimentation and self-expression of the 1970s were now passé -- and while the 'porn 'stache' would still flourish above players' lips throughout the coming decade, the Afro hairdo would be as dead as disco by the early '80s," Epstein writes. "Team uniforms gradually became, on the whole, less colorful, and so did the players themselves."

Of course there are exceptions, even today, Epstein said in a phone interview.

"The Giants have a couple of guys like [Tim] Lincecum and [Pablo] Sandoval, the Kung-Fu Panda, who seem like they could exist in the '70s. They're sort of '70s-like players. There's sort of a flamboyance to what they do; a joie de vivre that I find really appealing."

Cam Martin is a contributor to Page 2. He previously worked for the Greenwich (Conn.) Time and The (Stamford, Conn.) Advocate, and has written online for CBS Sports and Comcast SportsNet New England. You can contact him at cdavidmartin@yahoo.com.

|

| • Philbrick: Page 2's Greatest Hits, 2000-2012 |

| • Caple: Fond memories of a road warrior |

| • Snibbe: An illustrated history of Page 2 |

| Philbrick, Gallo: Farewell podcast |

-

TOOLS

- Contact Us

- Corrections

- Daily Line

- RSS