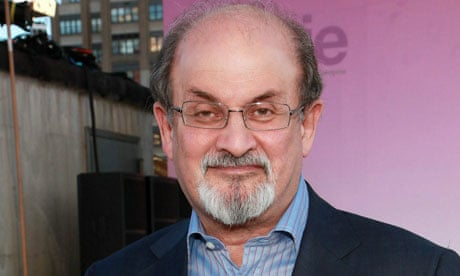

He was the superstar of postcolonial literature in the 1980s, the beleaguered poster boy for free speech in the 1990s, as he scuttled from house to house accompanied by special branch officers following the fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini in response to his novel, The Satanic Verses. But in the early years of the 21st century Salman Rushdie underwent a curious metamorphosis to become a figure of fun.

Partly this was due to his marriage to the Indian-American model and TV presenter Padma Lakshmi, a beautiful woman 23 years his junior who was also half a head taller. Newspaper gossips marvelled at the unlikely pairing, though it was hardly the first time a clever and successful man had attracted a talented younger woman. It could have been the novelty of the celebrity-in-hiding let loose on the New York social circuit: Rushdie met Lakshmi at a Tina Brown party, and was friends with lots of famous people.

Perhaps it was also the sense that the novels of those years – The Ground Beneath Her Feet, Fury, Shalimar the Clown – did not quite live up to expectations: that the apparatus of agents, advances and assistants had got out of sync with reality. Bono borrowed the title of The Ground Beneath Her Feet for a U2 song. The books, unlike Midnight's Children and The Satanic Verses, did not win prizes.

Next week Rushdie publishes a novel for teenagers – or rather, for one teenager in particular, Milan, his 13-year-old son by his third wife Elizabeth West. The book, Luka and the Fire of Life, is a companion volume to Haroun and the Sea of Stories, which he wrote exactly 20 years ago – in the dark early days of the fatwa – for Zafar, the son he had with his first wife Clarissa Luard.

The novel is a kind fatherly gesture: Milan knew about Haroun and wanted his own book. Rushdie clearly dotes on his sons: he grew up in a family of women and before his sons were born his family "had a real boy shortage, my three sisters between them haven't had a boy". But given his fame, it is hard not to see Luka also as a rebranding exercise by the 63-year-old writer: a deliberate step away from the big, ambitious, potentially prizewinning books towards something lighter, slighter and much more personal.

"The thing these books have in common is that the child has to rescue the parent, and I do think in some larger way, many parents would say that the experience of having children was a kind of salvation for them," he says, speaking from his home in New York.

In the book, which follows the formula of an old-fashioned quest, the young hero must complete a dangerous journey and has all sorts of adventures on the way. In the novel, Luka's father needs to be rescued from imminent death. In real life, Rushdie was miserable after Lakshmi, his fourth wife, ended their marriage three years ago (she has since had a baby with someone else), and his sons helped cheer him up. "It's very important to me to be a good father and I like to think I am," he says. "It's the deepest emotion you have. My sons are the most rewarding thing in my life and I can't imagine my life without them."

Is it not too much to expect of a child, that he should be your saviour?

"Yes, but children want to do it, children always think their parents are useless and need rescuing – even if it's only to show them how to use the computer."

It must be very strange to be Salman Rushdie. The fatwa was front-page news all over the world when it was issued in 1989, but it seems almost more extraordinary in retrospect, knowing as we do what came after.

While Rushdie himself escaped harm, and the threat was finally lifted in 1998, the Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses was murdered, there were attempts on the lives of two other translators and dozens of people died in riots in Turkey (still the only predominantly Muslim country where The Satanic Verses is legal). Long before most of us knew or bothered much about it, Rushdie was forced to confront radical Islam personally.

Two years ago, just a month after his novel Midnight's Children was for the second time judged Booker of Bookers, once more staking its claim to be the most important novel of the last 40 years, one of the police officers who had helped protect him during the fatwa years published a memoir. Ron Evans alleged that Rushdie had been known by his bodyguards as "Scruffy" and was once locked in a cupboard by officers "fed up with his attitude". Rushdie sued and won an apology.

Though angry with Evans, Rushdie says the experience did not leave a bitter taste, largely because other officers were so supportive.

But he has now decided to write his own memoir of those years, in part because "it made me feel that as long as so much of what happened is shrouded in secrecy, it allows people to do things like this, to make up stories".

Was he really frightened for his life in those years, or was it more of a nuisance?

"Some of each. There were some real and very concrete threats, and there was of course a natural frustration at the limitations."

Rushdie is the son of a Mumbai industrialist and at 13 was sent to board at Rugby, the English public school. His father was a cultured and charming man and also an alcoholic prone to violent rages. His mother gave up teaching when she married and devoted herself to her family.

"She knew where all the bodies were buried, she was a great gossip," Rushdie says. "She had the whole architecture of the extended family in her head, this colossal branching family tree. She could always tell you when you met someone that they were your third cousin's nephew's wife – and tell you everything about them." She was also great at golf.

The family, originally from Kashmir, was secular and liberal – all three of Rushdie's younger sisters had careers and none had arranged marriages. When asked for his opinion of the new French law banning the veil, he refers to the passionately held views of the women in his family.

"Don't ask me to defend the veil because I won't," he says. "Women in the west who use it as a badge of identity, which I think increasingly younger women seem to be doing, I think that's what used to be called false consciousness. The battle against the veil is a serious matter in the Muslim world."

Such views illustrate why some in the western liberal establishment who once feted him no longer find Rushdie congenial. And there were raised eyebrows as well as sincere expressions of support when, to the rage of Muslim fundamentalists, he accepted a knighthood in 2007 from the Queen. He has offended Indians too, with his famous pronouncement in the introduction to a 1997 anthology, that "India's best writing since Independence may have been done in the language of the departed imperialists" (ie, English).

When he left Cambridge in the 1960s, he felt he had little choice but to settle in London if he was to make it as writer. Things are different now and were he faced with the same choice, he might well stay in India.

But he distances himself from the polemical anti-religion stance taken by his friend Christopher Hitchens, and has spoken in support of the proposed Islamic centre two blocks from Ground Zero. "I'm not a big fan of mosques, I'm not a great fan of mullahs," he says. But, he adds, "of course people should have a place to be able to observe their religion. If that place stopped being a hole in the ground – well it's no longer a hole in the ground, there is building taking place … but the sooner it can go back to just being part of New York City, the better".

While his accent is undeniably English, it is hardly the patrician public school caricature that is sometimes implied. Does he recognise the portrait of himself drawn by the press? One recent magazine profile made it sound as if the merest mention of the fatwa could prompt him to fly off the handle.

"It seems to me that what the media sometimes do is create a narrative for you and then insist that you live inside it," he says. "But what am I supposed to do? I can't go round correcting every newspaper article that comes out."

Did he ever play along with this cartoonish image, find it funny even? "No fun at all. Ugly, reprehensible, disappointing. Being lied about in print, you wouldn't like it. And I don't either.

"I think I'm quite a nice guy actually and I have a lot of friends who would defend that position."

Rushdie has stayed in New York – an apartment in midtown Manhattan – since his divorce and divides his time between there and London. In a few days, Zafar will arrive for a visit. In the UK, Rushdie remains closely associated with old friends Ian McEwan and Martin Amis. In New York, his literary friends include Don DeLillo, Paul Auster and Peter Carey.

He has brought up his sons to be global citizens: Luka and the Fire of Life is, among other things, a kind of globalised mythology featuring deities from multiple continents. In one passage, Amaterasu, the Japanese sun goddess, stands guard alongside the Norse giants Surtr and Sinmara, Irish Bel, Polynesian Mahuika, Iame Hephaestus "the smith of Olympus", Inti of the Incas, the Aztec Tonatiuh, and "towering above them all like a giant pillar in the sky was falcon-headed Ra of Egypt".

Rushdie knows there is plenty of anti-Muslim feeling around in the US but says he has not been the target. "It's very strange being somebody of Indian or south Asian ethnicity in the US, because in some way we are excused American racism, which is mostly whites against African Americans … American racism is not aimed at people from India and Pakistan, you feel almost guilty about it."

In England, on the other hand, he feels anti-Asian prejudice remains pointed. "I sometimes feel terms of abuse like 'Paki' seem to carry more weight than attacks on African and Caribbean people … that the focus of those people who are racist is more towards south Asian migrants and their children than towards the African and Caribbean community, although not being one of those people it's difficult to say."

Rushdie was almost 50 when Milan was born and the new book, with its death-cheating adventures, is partly about the older father's fear that he will not live to see his son grow up. "There was an extraordinary moment when he was born, my boys and I have birthdays within about three weeks of each other, so there was a moment when Milan was zero, Zafar turned 18 and I turned 50, so we had these three enormous milestones all happening at the same time. I must say I felt it when he was born. I thought, I'm a pretty old parent, when this child is 20 years old I'll be 70."

Does he have any regrets about his failed marriages? He remained on friendly terms with the mothers of his two sons (when Clarissa Luard died in 1999, Rushdie gave the funeral address), while the other two breakups were more acrimonious.

"You can't regret your life in some way," he says. "If I had remained married to my first wife, even if she hadn't passed away, then I wouldn't have my second son.

"I remember when I was a student of history one of the things professors would say to me is that the question of 'What if?' is not an interesting question. It's hard enough to understand and come to terms with what actually happened, without trying to wonder what might have happened if something else had been the case. This is the life I've had."

Luka and the Fire of Life is published by Jonathan Cape