Wonderful Centipedes: The Poetry of Tomas Tranströmer

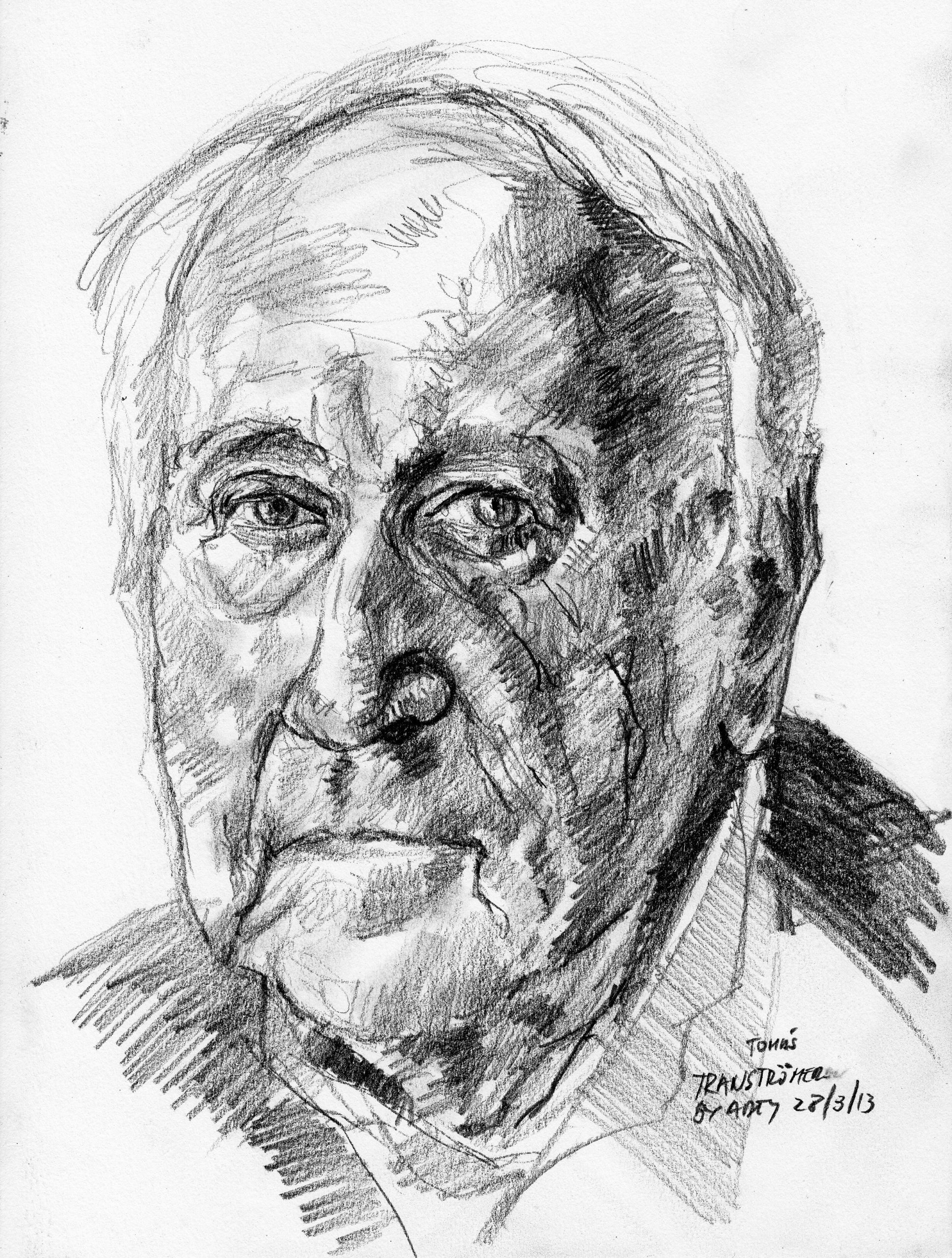

Arturo Espinosa, Tomas Tranströmer, 2013 (CC)

Arturo Espinosa, Tomas Tranströmer, 2013 (CC)

by Niklas Schiöler

The opening lines of Tomas Tranströmer’s poem “Schubertiana” from 1978 are:

In the evening darkness at a place outside New York, an outlook where

you can perceive eight million people’s homes in

a single glance.

The giant city there is a long flickering drift, a spiral galaxy

from the side.

But soon, after the snapshots of the grim and chilly human conditions of the giant city, the first part of the poem ends with these relief-giving lines:

I know too – without statistics – that Schubert’s being played in

some room there and for someone the tones at this moment

are more real than anything else.

A radically different scene is depicted, and suddenly the attention is directed differently; a detail dashes in which makes everything else insignificant. The zooming-in catches a spark of life in the middle of the concrete urban landscape.

It is later on in the poem, that after having enumerated some of daily life’s inevitable worries, a stunning image appears. The music makes us, the poem whispers in our ears, believe in something different, something more urgent and important – and Schubert’s string music escorts us a part of the way there.

Like when the light goes out on the stairs and the hand follows –

with confidence – the blind banister that finds its way in the

darkness.

Thus, the invisible becomes concrete and the hidden truths become discernible. It is a vision that interprets the world.

Gustav Klimt, Schubert at the Piano II, 1899

Gustav Klimt, Schubert at the Piano II, 1899

Perhaps it is this curious view of life, shaped with such visual exactness, and at the same time, with quiet matter-of-factness, that draws ever more readers to Tranströmer. His poetic investigation of the complex human identity, as well as his construction of bridges between nature, history and the dead never results in structured patterns or in loud-voiced confessions. His poetry is a tranquil affirmation of few words.

The lure of existential secrets, the sensibility to our inner sources of energy, is invoked by Tranströmer’s concreteness. No sweeping statements, no abstractions. By recording the particulars of the physical world, wider connections can be perceptible and the liberating insights can emerge.

Here we have, I think, one of Tranströmer’s most definitive characteristics in his way of writing; an artistically effective contradiction in that his millimetre precise sharp-sightedness that draws us nearer to the irrational and spiritual. The mental regions are made visible only by the instruments of exactness.

Shaping the unspeakable with words for Tranströmer is not the same as to define the unspeakable; which many would call God, soul, meaning, or death. Poetically though, one could can sense a trace, or catch a glimpse of something that might transform the material to the unspeakable, or to The Great Enigma, the title of his latest book.

In a way Tranströmer, with his constantly varying imagery, postulates that man’s frontiers always are drawn further away than we normally expect, ”We don’t really know it, but we sense it: there is a sister ship to our life which takes a totally different route.” [1] Tranströmer has previously referred to his poems as ”meeting places”, with their intent to make a sudden connection between aspects of reality that conventional languages and outlooks ordinarily keep apart. What seems to be a confrontation reveals a connection.

Therefore, the enigmatic illogical is expressed as something natural, and the dreamlike as reality. And what I believe is important is that many of the starting points of his poems are quite familiar; a trip by car or a walk in the woods. Often we meet a world that looks like those in which we spend our daily time.

The unpretentious and the sublime have made an aesthetic alliance. Free and easy, his poems marry the physical and the mental, the past and the present, and in glorified moments all restraining straitjackets are untied: the marvellous arrival of springtime is described in a poem as when ”a kilo weighed just 700 grams”. [2]

Nevertheless, the darkness and the disharmony are never far. Sometimes even the concealed traffic between different apparently incompatible existential dimensions is slow-flowing. “In the slot between waking and sleep / a large letter tries to get in without quite succeeding.” [3] And there, we could have started, as in the contemporary commitment, with Tranströmer’s protection of the individual against repressing powers and authorities.

To be contemporary can, however, mean various things. In the sixties, Tranströmer was criticized by younger poets for not being interested enough in social affairs. He was considered to be too much poetical, too little political; too much contemporary with Horace, too little with Marx. But if you read more carefully, you will notice in his poems just how crucial international issues and fragments from his work as a psychologist are expressed. Besides which, he has always seen insufficiencies in both Marxist and commercially blunted optimism.

”Every problem cries in its own language”[4], he writes in a poem. Poetry has to be an active resistance to the stereotype languages of power, mass media and the market. Instead of standing on the barricades, Tranströmer travelled to the Baltics around 1970, and was there defending artistic freedom. He also smuggled poems to his colleagues. For instance, he writes in the poem “To Friends Behind a Frontier”[5], in which a letter to his friends behind the iron curtain is read by the censor. “He lights his lamp. / In the glare my words fly up like monkeys on a grille, / rattle it, stop, and bare their teeth.”

The last stanza is an outstretched hand to the oppressed, and a poetic fist straight into the solar plexus of dictatorship:

Read between the lines. We’ll meet in 200 years

when the microphones in the hotel walls are forgotten

and can at last sleep, become trilobites.

Fortunately, a great deal of readers have managed to access Tranströmer’s poems in less complicated ways (and here I would like to pay homage to all translators, especially when the Swedish language only can be understood by less than one out of a thousand people on earth): today, Tranströmer can be read in at least 60 languages.

Where to place the point his writing is a tricky question, but I think that it is impossible to eliminate the signs of the non-material and the spiritual aspects of his poetry. These ethereal qualities remain intertwined with the social issues. The spiritual dimensions are like gestures to other layers of existence, inside the individual, or like signals from outside, waiting for the sensitive poet to catch.

Belief, or faith, in his poetry, is, as I see it, never uncomplicated, and is never a definite answer. Tranströmer’s senses are wide-opened to the complex, to all impulses, and therefore he lets himself be surprised.

Perhaps, what you could say about his poetry is that the remarkable things in life aren’t hidden away from us; but we have to be alert, watchful because they do not make a great fuss and they are not noisy.

If one would wish to get closer to these qualities in Tranströmer’s poetry, I believe music is the channel. And the poem which most profoundly gives us the significance of music is possibly “Schubertiana”, of which I’ve already quoted. It tells us about the sacred and the healing powers of music.

Schubert’s Die Nebensonnen from Winterreise

Schubert’s Die Nebensonnen from Winterreise

The composer, Schubert, on which Tranströmer writes, can probably be interpreted as the poet himself. Schubert stood in the morning at his desk, ”at which the music script’s wonderful centipedes set themselves in motion”. The text’s wonderful centipedes set themselves in motion. And they set themselves in motion in an authorship that is quantitatively small, but in these few words, the world’s surprising and great variety is absorbed.

That’s why Tranströmer’s poetry can offer an important aesthetic alternative to materialism’s superficiality, and why it can be a source of wonder and trust in a secularised society. After reading his poems, we don’t experience the world in the same way as before. The senses have been washed.

I know too – without statistics – that in some room over there in New York’s flickering spiral galaxy, someone right now is reading Tranströmer.

References

The first set of quotations are from “Schubertiana”, from The Truth-Barrier, 1978, translated by Samuel Charters, in TT, Selected Poems 1954-1986, transl. by Robert Bly a.o., ed. by Robert Hass, Ecco Press, New Jersey, US, 1987, p 143f.

[1] “The Blue House”, from The Wild Market Square, 1983, transl. by S.Charters, in Selected Poems 1954-1986, transl. by Robert Bly a.o., ed. by Robert Hass, Ecco Press, New Jersey, US, 1987, p166.

[2] “Noon Thaw”, from The Half-Finished Heaven, 1962, in TT, Collected Poems, transl. by Robin Fulton, Bloodaxe Books, Newcastle 1987, p 58.

[3] “Nocturne”, from The Half-Finished Heaven, 1962, transl. by Robert Bly, in TT, Selected Poems 1987, p 62.

[4] “About History”, from Bells and Tracks, 1966, transl, by R. Fulton, in Collected Poems 1987, p 76.

[5] “To Friends Behind a Frontier”, from Paths, 1973, transl. by R. Fulton, in Selected Poems 1987, p 107.

About the Author

Niklas Schiöler is a writer, a literary scholar and Associate Professor at Lund University, Sweden. He has published extensively on Tomas Tranströmer.