Modernists and feminists

The 'poem including history' and the 'autohistoria'

Multilingualism has long been a key characteristic, even a central tenet of literary experimentation. So maybe it seems a bit weird that after all these commentaries I still haven’t found anything to say about the various streams of modernist literature that drew upon other languages. Why haven’t I addressed T. S. Eliot's attempted reconstitution of the “mind of Europe”? What about Ezra Pound's (also attempted) translation of Chinese written characters? Or what about the less well known but no less multilingual Zurich Dada “nonsense” poems that drew upon anthropological works, using fragments and phrases from world Indigenous languages to inform their experiments in non-meaning?

Analyses of avant-garde or experimental poetry typically understand multilingualism as a part of the modernist dream of breaking with the past in order to prefigure an unforeseen but possible future. In this version of the story, the use of multiple languages is a means of extending the poem’s epic ambitions and temporal reach, a practice that the Mexican poet-critic Heriberto Yépez has called “the psychopoetics of empire.” In venturing beyond their own languages, Yépez argues, modernist poets constructed an “imperial fantasy” in which they could gather past, present and future into a single place and time; this “transhistoric consumerism” assured their cultural centrality (31).

I’m quite persuaded by Yépez’s analysis, which he builds through a detailed consideration of Charles Olson’s sojourning in Mexico. Given the politics and commitments of contemporary multilingual poems and their poets, then, high modernism is a precursor with limited explanatory value — I'm sure some contemporary poets would quite like to assure our cultural centrality, but the "imperial fantasy" part has (hopefully?) gone out of style. Although the avant-garde techniques through which modernist writers incorporated other languages recur in contemporary multilingual poems, I find that contemporary poets tend to avoid the modernists’ unifying impulses, the desire to “make it cohere,” in Pound’s words, in a total system. Yépez’s critique of the imperialist overtones of modernist multilingualism exemplifies a different set of political-poetic concerns that shape the use of multiple languages in contemporary poetry.

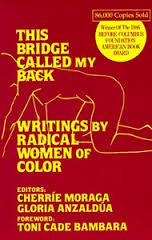

There’s another obvious precedent for contemporary multilingual poetry that is too often ignored within conversations in contemporary poetics: the proliferation of feminist writing in the 1980s that made linguistic experimentation a critical component of its innovations in genre and in politics. Cherríe Moraga’s Loving in the War Years: lo que nunca pasó por sus labios (1983), Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), and their collaboratively edited anthology This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) stand as three of the most well-known examples produced in the United States. In Quebec, similar experiments in multilingual feminist writing integrated considerations of gender, sexuality, and the post/colonial condition — one of the key texts of this moment, the collaboratively authored Theory, A Sunday has just been translated and published by Belladonna*.

Feminist writers in the 1980s combined languages as well as genres in order to create new literary forms suited to describing their experiences, to writing the self as collective and individual, as historically and politically situated, and as an unfinished project, a construction in progress. They juxtaposed history, myth, fantasy and anecdote, and experimented with essays, sketches, short stories and poems. Their texts uncover and describe the historical and material conditions and cultural forces that contribute to their authors’ fractured, mutable, and conflictive sets of identifications.

Especially when writers such as Anzaldúa and Moraga are viewed alongside their avant-garde contemporary Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, the politicized multilingual experimentation employed by feminists in the 1980s can be seen as forming a broad foundation, formally and politically, for contemporary multilingual works. Works like This Bridge Called My Back, Borderlands, and Theory, A Sunday are especially significant precedents for contemporary multilingual poetry not only because they emphasize the importance of considering issues of citizenship, boundary crossing, race, ethnicity, sexuality and language together, but also because these works make clear that poetry is a genre in which important theoretical work is accomplished. For feminist writers, formally innovative poetry and multi-genre writing most clearly expressed the lived reality of intersectional identities, and were the modes of writing open to broad-based participation by non-elite practitioners.

When I think about the roots of contemporary multilingual writing, I do think about the modernist “poem including history.” But I also think about the feminist “autohistoria,” to use Anzaldúa’s term. It’s a precedent that receives detailed consideration in poetry, and I think it deserves much more explicit consideration in poetics.

Languages