Alipur Road was a wide avenue lined with enormous banyan trees, and my mother and I would go for walks along it – to Maiden’s Hotel, which had a small library, or further on to the Quidsia Gardens. And, across the road, I’d see a young woman pushing a pram with a baby seated in it and a little girl dancing alongside it. She was a married woman clearly, and I a student at the University of Delhi, but glancing across the road at her, I felt an instinctive relation to her. Why?

She was revealed to be a young woman of European descent – German and Polish – who was married to an Indian architect, Cyrus Jhabvala, and lived in rooms in a sprawling bungalow just off Alipur Road. When her mother, a German Jewish woman from London, visited her, Ruth searched for someone she could talk to. I think it might have been Dr Charles Fabri, the Hungarian Indologist who lived in the neighbourhood, who suggested she might meet my German mother, who had also come to India on marrying an Indian, 30 years before, in the 1920s.

A coffee party – a kaffeklatsch – was arranged so the two could indulge in their shared language in this foreign setting. I can’t imagine how or why, but Ruth decided to follow their meeting, after her mother had returned to England, with many others, on a different level – that of daughters. With extraordinary kindness and generosity she would have me over to their house, one filled with books, the books she had brought with her from England where she had been a student at the University of London when she had met Jhab. Perhaps it touched her that I was so excited about being among her books, talking to her about books. After that whenever I came away with an armful of books on loan, with her talk still in my ears, I felt elated, a visitor to another world, the writers’ world I had only imagined and now proved real. I would go home to scribble at my desk with a new, unaccustomed sense of the validity of such an occupation.

One day she placed in my hands a copy of To Whom She Will, her first novel that had been published in faraway England, an unimaginable distance from Alipur Road, Old Delhi. Holding it, I felt I had touched something barely considered possible – that the scribbling one did in one’s hidden corner of the world could be printed, published and read in the world beyond

. Could our drab, dusty, everyday lives yield material that surely belonged only to the genius of a Chekhov, an Austen, a Woolf or a Brontë? Taking home the copy Ruth inscribed for me and reading it, I made the discovery that she had found, in this ordinary, commonplace world I so belittled, the source for her art, the material for her writing, using its language, its sounds and smells and sights with a veracity, a freshness and immediacy that no other writer I had read had. The message was like an electric current: yes, this is our world, our experience, it can be our writing too.

Many years, much experience later, we once had an unexpected encounter in the airport in Frankfurt. She was on her way from New York to India and I was on my way from India to New York. Alarmed at my lack of proper clothing, she insisted on giving me her duffel coat that she would not need in India but I would in New York. So we made our separate ways, across the hemispheres, safely.

In the years that followed, we shared so much, or looked at differently, so little: our lives were small, restricted. The Jhabvalas moved to the beautiful house designed by Jhab on Flagstaff Road, and there were now three daughters – and two enormous German shepherds. I too married and had children and would take them over for tea, which they would greatly look forward to because Ruth always had her cook, Abdul, bake a cake for them and Jhab would come back from his office to entertain them with his repertoire of magic tricks.

In the summers we met in the “hill-station” of Kasauli where the Jhabvalas booked rooms at the Alasia Hotel every year, while I stayed in a rented cottage nearby. Our children would run wild in the pine woods on the hillsides while Ruth and I went for our more sedate walks and occasionally met Khushwant Singh, the Sikh historian and novelist who also had a home there.

In all these orderly, regulated, uneventful years, Ruth wrote prolifically: novels and short stories that seemed to draw on a bottomless well of material. She always had such an air of existing in a separate world, in isolation and perfect stillness, so where did all this come from? Where – how – did she come to know the men and women who peopled her books?

We need to listen to her: in her 1979 Neil Gunn Fellowship lecture she said that as a Jewish refugee from Europe, the loss of her inheritance made her “a cuckoo forever insinuating myself into others’ nests”, “a chameleon hiding myself in false or borrowed colours … You take over other people’s backgrounds and characters. Keats called it ‘negative capability’.”

It was a contrast to what EM Forster and Paul Scott had done in their writing about India – as outsiders and visitors, if fascinated observers. Caryl Phillips has remarked that Ruth was “postcolonial before the term had been invented”. Her own explanation was typically understated and wry: “Once a refugee, always a refugee”.

Once she had VS Naipaul to tea and passed him a plate of cakes. He pointed at it with a trembling finger and cried: “There’s a fly on it!” “Oh,” she said, “just take off your glasses. I always do.” But not when she was writing, when her vision was laser sharp, nothing was glossed or obscured.

Ruth’s characters were not likely to be speaking English, they would be speaking Hindi or Urdu or Hindustani. So there was a translation going on – yet there was no hint of the strain and uneasiness of crude, satirical and parodied translation of an Indian language into English that we encounter today. Hers was a total absorption. Ruth, like a great actor, becomes her characters and presents them to us from the inside out, not the outside in. She does not criticise or satirise them – as so many Indian readers accused her of doing – she becomes those she portrays.

It was her fate to be presented to western readers as an Austen but although she does share her wit, precision and asperity, she was not ever Jane Austen at a ball, watching the flirt, the sharp-eyed mother or the tittering gossip – she entered into and inhabited her characters, herself withdrawing.

I think none of us in India knew what an immense drain this was on her energy, her resources. Not until we read her extraordinary essay “Myself in India”, in which she wrote of the split, the fracture between her western sensibility and her eastern experience, which is made plain in the first line: “I have lived in India for most of my adult life. My husband is Indian and so are my children. I am not, and less so every year.” She went on to reveal the exhaustion relating to the constant to-and-fro of her love and loathing for her adopted land. “I think of myself as strapped to a wheel that goes round and round and sometimes I’m up and sometimes I’m down.”

This was when the subject of her work changed to the Europeans who came to India, the hippies of the 60s and 70s, unlike herself in search of the exotic – whether spiritual or sexual, they hardly knew themselves, often confusing the two and finding it in the charismatic and unscrupulous figure of the guru.

Ruth became ill, her family worried about her. In those days if she ever saw I was myself going through some anguish over life or writing, she would not question or probe but instead rally me – and perhaps herself – by quoting Thomas Mann: “He is mistaken who believes he may pluck a single leaf from the laurel tree of art without paying for it with his life,” or asking, laughingly, “What would you rather be – the happy pig or the unhappy philosopher?” making light of it but not taking it lightly herself.

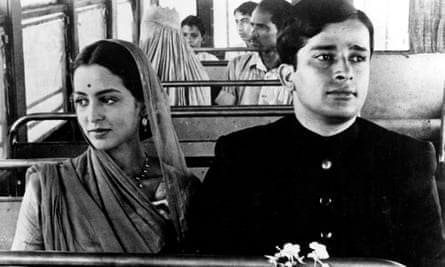

It must have been at this time that James Ivory and Ismail Merchant entered her life when they came to India in search of material for a film. They found it in an early novel of hers, The Householder, which she adapted for the screen for them. She said “Films made a nice change for me. I met people I wouldn’t have done otherwise: actors, financiers, con men,” and moved to New York, buying an apartment on the Upper East Side where Ismail and Jim lived.

I saw less of her in these years although I moved to the US myself, not to the film world but the academic one of New England, but kept in touch through her writing. Apart from the film scripts she wrote – including the adaptations of novels by EM Forster for which she won Academy awards – for Merchant Ivory Productions, she now wrote only short stories that she said she loved “for their potential of compressing and containing whatever I have learned about writing and about everything else”.

She found a new rich vein in the lives of the Jewish European refugees, the people she might have known in the past, who had come to the US and could be observed in the grand hotels and restaurants of New York and Los Angeles. One can discern in these stories her continued fascination with the false guru, who in America takes the form of the temperamental artist, the supposed genius, attracting women who submit to his stormy tempers and selfish demands.

For such a quiet, still person it is extraordinary what strong passions each story, novel and film contains. She never shied away from them and continued to address their immense potential for both joy and destruction with a clarity of vision unobscured by any wisp of illusion. Clear, cool, dry and infused with wit and insight, her style was the mirror of her person, the poise and elegance of her being.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion