The Millennium Falcon in My Stomach; or, A Plastic Token of Disease and Indifference

A film conversation between Gregory Giles and Teresa K. Miller

Teresa K. Miller

I.

On the shores of Midway Island, the juvenile albatross skeletons encircle a stomach’s worth of plastic shards, pen caps, bottle tops, the insidious end to all species’ endocrine systems innocuously named “nurdles.”

In Oakland—whence, in Oregon, we dare not say we’ve come—I watched the short film Midway: A Message From the Gyre (2009) and was wrecked for a day. A Plastic Ocean (2016) shows scientists rescuing animals by flushing their stomachs of indigestible fragments of human garbage or studying the corpses of those who’ve died, but the film doesn’t dwell on the in-between: the convulsing baby birds on their sides, slow starvation curling them toward the position in which the camera would later find stripped bones.

The insidious end to all species’ endocrine systems innocuously named “nurdles”

We dream of the ocean as infinite, an expanse so deep and dark that searching for 239 people on a plane could prove no more fruitful than seeking a specific grain of sand on a beach. Its size defies comprehension such that we mistake it for being endlessly able to hide our refuse—such that our societies still cannot shake the deadly adage “The solution to pollution is dilution.”

II.

A nervously laughing Israeli settler in Our Water, Their Water (2011) describes how her family saves water by doing only one load of laundry a day, while the Palestinian man only a few hundred yards away—but also a universe away, on the other side of a wall—shows the rusty, sedimented bottom of an empty cistern as his wife laments the difficulty of getting water for her children to drink. Though the Israeli lives in a newly constructed house where water flows from the tap at no great cost to her, another Palestinian lists his community’s digestive ailments wrought by saltwater intrusion into overexploited aquifers.

Palestinians pay to truck in drinking water when the wells run dry, and without irrigation water, many of the farmers among them are also forced to work in the very Israeli settlements that have served to strip them further of their sovereignty. Those who continue to cultivate rain-fed crops, such as olive groves, face sabotage: Since 1967, approximately 2.5 million mostly fruit-bearing trees have been uprooted on Palestinian lands.

III.

Photographer Pete McBride wanted to paddle the length of the Colorado River but ended up in a gray froth along the Mexican border, dotted with discarded plastic bottles and bearing no resemblance to water. He and his companion hit a dry, cracked plain and had to walk the last 90 miles to the Sea of Cortez. The once-mighty Colorado is so over-consumed that 2014 was the first time it had made it to the sea in 16 years, and then only with the aid of human intervention and at only 1 percent of its natural flow. (Research by a Dutch NGO indicates that if all Americans abstained from eating meat just one day per week, the resulting reduction in their water footprint would equal the river’s total flow.)

Dotted with discarded plastic bottles and bearing no resemblance to water

In Utah this past September, your uncle recommended that we go to the confluence, where the Green River meets the Colorado. We didn’t have time to make the trek down the canyon in the desiccating 100-degree heat, but we saw the two from above, having walked out to the furthest point on the mesa in Canyonlands National Park. I kept picturing us tumbling hundreds of feet into the vertigo-inducing valleys the rivers had carved over millennia, and I wouldn’t let you sit on the very edge. Sorry (sort of).

We went to the source of the river, the Rocky Mountains, and found snow at Emerald Lake in early September. On the way back west, we joined the throng of tourists camping at the edge of Lake Powell and chose our tent site amidst the thrumming RVs. We’ve written about the consequences of that lake, backed up against Glen Canyon Dam, drowning historical indigenous sites at the bottom of a canyon the Sierra Club has been accused of trading to preserve other, more popular monuments.

I wanted to see it for myself. You did not man a houseboat and nearly run it into a canyon wall, as in your childhood, but we inhaled the spewing exhaust as a pilot worked to dislodge one from the sand. Still, it was not all mourning destruction: We spent hours in the water to stave off the midday heat, dried off and cooked dinner in the tent shadow, watched the sun set behind striped rock formations. In the unlit desert, thousands more stars appeared than we’re used to. I woke to see the sunrise—but also the white “bathtub rings” that McBride laments, left behind by the precipitously dropping water levels after decades of drought.

I kept picturing us tumbling hundreds of feet.

IV.

Then there’s the easy, upbeat story of the Milagro beanfield, made at a time when it was typical, though not universally accepted, for a white man like Robert Redford to direct a film about a Chicano resistance in the Southwest and cast an Italian-American New Yorker in the lead role. The community prints one critical article in the tiny paper, has a meeting, keeps opening the gate to let the irrigation water run into the family beanfield instead of down to the resort under development that has commandeered the water rights. People are shot, but no one dies. The sinister federal agent is thwarted and goes home frustrated, the permits for the development are pulled, and the gringo carpetbagger pitches a fit. The righteous community prevails. It has not been so easy in the real world, as in Bolivia, where Víctor Hugo Daza was killed while protesting increased rates accompanying privatization of the water system.

V.

In outdoor survival and disaster preparedness trainings, we learn that depending on the circumstances, a human can survive three weeks or more without food—but only three days without water. Aside from air, it is our most essential substance. For some, this fact indicates the need to codify water as a fundamental human right and keep its allocation and distribution under public control. Others see a captive audience and the potential to reap tremendous profits through privatization at a time when fresh water is becoming increasingly scarce as a result of climate change, soaring population, and pollution.

Under the banner of cutting costs in the city of Flint, officials switched the water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River, and the new supply corroded old lead pipes to such an extent that in some households, water flowing from the tap met EPA criteria for hazardous waste, with lead levels as high as 13,200 ppb—compared to the legal limit of 15 ppb. It is a variation of the oldest American story of maintaining wealth and power through the unwilling sacrifice of poorer people and people of color.

A couple years ago, not long after my critique of Big Ag PR strategies for the think tank Food First generated some Twitter buzz, a cofounder of the hedge fund Water Asset Management (“WAM” for short—the sound of being bludgeoned by the unchecked private sector?) followed me on that platform. I don’t know if the suggestion algorithm went haywire or he thought Food First might call out his company by name next, but having read and heard about water privatization and profiteering more generally, it was strange to see his individual face pop up in my personal notifications.

His profile’s selfless-sounding hashtags aside, the company’s stated goal is to serve its investors and ensure “the long-term success of its investment funds.” Confoundingly, WAM’s own website prominently features a ProPublica article describing cofounder Disque Deane Jr.’s goals in stark terms:

Deane looks at the drought, the perennial mismanagement of water in the American West, and the region’s growing population, and believes a reckoning is coming. Rising demand and shrinking supply virtually guarantee that water’s value will increase. Anticipating that day, he’s racing to buy up as much of it as he can. … Where government has failed, Deane believes capitalism offers an elegant solution. Allowing people to buy and sell water rights is a more expedient way to redistribute the West’s water, he argues. … He’s convinced that this is our best hope for ending the West’s water shortage—and that it could make him and his investors very, very rich.

The article goes on to describe the experience of Crowley County, Colorado, where individual farmers sold off their land and accompanying rights, the water was taken from the area, a tipping point was reached, and the local economy collapsed: “Though tens of millions of dollars in water rights were sold, few of the proceeds were reinvested in the community.” Shipping the water elsewhere caused not only the community’s finances to dry up but also the physical land, which does not have the conditions to return to natural prairie and is instead losing topsoil to wind and undergoing desertification. It can no longer support wildlife, leading to the exodus or demise of animals and pollinator colonies.

I do not object, in principle, to a system that puts a price on resources in order to incentivize more environmentally sustainable behavior—I support a carbon fee and dividend, for example. But in that instance, the system a) works in the opposite direction of privatization by protecting the atmosphere as a part of the commons and attaching costs to what were previously externalities and b) includes an equally distributed refund so as to be inherently progressive rather than regressive in its economic impact on consumption of basic necessities.

Officials switched the water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River.

What, by contrast, protects the public interest—access to the basic human right of clean drinking water—when a private water fund takes control? Investors can passively place their money with men who will scout out the water rights of distressed farmers grappling with “debt, death, and divorce” (WAM’s words) or, as public utilities become privatized, will serve as the profit-protecting intermediaries in the next Flint—allowing us to avert our eyes as our fellow citizens shoulder water in ubiquitous, expensive, and polluting plastic bottles to replace what comes from their toxic taps.

Gregory Giles

Ocean conservation is a phenomenological problem. Mountaintop removal mining in Appalachia, by contrast, affects visible skylines, butchering the natural topography, visually signifying the alteration of “unseen” ecosystems, aquifers, vascular watersheds threading forests, and toxicity levels that do not register immediately in appearances. The ugly transformation of familiar sights triggers a disheartening sense that something terrible is actually happening to our world, without any environmental impact study at hand to confirm it. A mountain—a conventionally natural sublime monolith seemingly beyond the transformative reach of humans—is no longer Edmund Burke’s source of Enlightenment terror and ecstasy within an individual’s inadequate estimation of the infinite, dwarfing and mocking human endeavor. Instead, it’s simply a pitiful victim of global capitalism’s manifest destiny.

Finitude destroys the sublime, as Burke insists: “[L]et it be considered that hardly anything can strike the mind with its greatness, which does not make some sort of approach towards infinity; which nothing can do whilst we are able to perceive its bounds; but to see an object distinctly, and to perceive its bounds, is one and the same thing. A clear idea is therefore another name for a little idea” (On the Sublime and Beautiful, Part II, Sec. IV). What terrified and isolated the Romantic poets in humbling (or more likely, arrogant) subjectivity is now just excreted tailing, the environmental externality of an industrial process. The planet no longer offers suggestions of the infinite to human comprehension, with the possible exception of the ocean.

The quaintness of the Romantic sublime—mostly defeated now by exhaustibility, or “bounded perception,” as Burke might describe it—is reinvigorated somewhat by the ocean’s vastness and inaccessibility to idle encounters. Oxygen tanks, nylon rope, and freeze-dried bodies encased in Gore-Tex, fleece, and goose down vividly litter the well-worn final summit to the top of Mt. Everest. The gaudy colors of synthetic fabric outlast the frozen bodies they shroud, diminishing the ghoulish impact of their presence, more resembling mannequins in a sporting goods store knocked to the ground during the chaos of annual inventory. The disjunctive sight of artificial colors and human queues of unlucky or inadequately skilled mountaineers scaling the Olympian geometry of the highest Himalayan peak overlays the extreme adventure with something more visually mundane: consumers at an outdoor shopping mall, perhaps, waiting in winter cold for the chain store to open on Black Friday. But oceans still retain something of the purely conceptual, more or less humbling to the individual, as I discovered crossing between Fiji and Vanuatu on a 40-foot steel-hulled cutter: swells as high as the sailboat’s mast during an unseasonable gale, the vessel beating the prevailing wind, no horizon in sight, no sense of progress, just successive walls of pewter-colored ocean, unpredictably violent motion. I was simply a human organism vomiting bile, clipped to a lifeline, sleeping fitfully in the open cockpit for the fresh air, a meaningless dot inscribed on a blank chart with a “here be dragons” annotation. A flying fish won the lottery of misfortune—a one in a billion chance—and struck a capstan near the prow at high velocity, killed upon impact by a measurement in time and space only registered by an orbiting GPS, newly available to consumers in 1993, long before every human above an abject level of poverty would have a personal signal enforcing subjectivity. It was strangely reassuring of my existence to see another luckless organism gawking on the deck, killed by a triangulated point.

“To see an object distinctly, and to perceive its bounds, is one and the same thing.”

In our contemporary world, we need a synecdochical monster of comprehensible breadth in order to feel justified in resisting our own complacent plastic waste production. Without it, we are dangerously slow to act. “Monster”—as the word’s Latinate etymology tells us—originally referred to mere visible tokens or omens; the qualitative evil of monstrosity adhered later. But it behooves us to understand our desire for monsters in the most rudimentary sense; for example: the Pacific’s equivalent of a Sargasso Sea of plastic covering an area the size of Texas, rotating like a galactic body in an oceanic gyre, widely reported in 1997 when Charles Moore “discovered”/coined it. There is no visible raft of plastic the size of Texas, as it turns out, but the imagination is captivated and urged by the singular tactile mass of this threat—a tumorous object growing in a pristine bath. Moore himself disowns the description, understanding that being disappointed by the monster’s visible absence will only embolden petroleum industries eager to discount environmentalists. In the same way, scientists regret the coining of “global warming,” a unidirectional term vulnerable to opponents like Republican Senator James Inhofe from Oklahoma—who, testing the intelligence of his constituents, brought a snowball to the Senate floor as proof of a stable climate. The altogether clinical “climate change” dampens our alarm, the more accurate term depending on individuals’ physically rendering the conceptual, a concretizing skill that is also dependent on mental effort perhaps only encouraged by ideological predisposition.

The reality is far worse than a plastic island the size of Texas, if less fathomable and less amenable to direct action. Microplastics season the oceans with toxicity, their infinitesimally textured surfaces capturing toxins efficiently, creating plankton-sized nodes of poison that are swallowed by every form of ocean life with a gut. While not as uniformly present as sodium, microplastic pollution saturates the oceans enough that a European with a taste for shellfish, for example, is also consuming 11,000 particles of plastic per year. The Midway albatross is only a more visible sign: convulsing, dying, and disintegrating, the stomach decomposing from its colorful nest of plastic nurdles—the remaining feathers and bones surround the tidy pile like a beach altar arranged purposefully. If I developed pica and compulsively ate Legos until they blocked my intestinal tract, leading to malnutrition, ulcerations, sepsis, and, ultimately, my death, you could donate my 14-stone corpse to a body farm where they would observe the impressively ghastly stages of putrefaction, eradicating my individuality and any trace of my illustrious life, leaving bones that will sooner become soil than the pile of Legos also left behind, which you could then wash, repackage, and sell to a boy who would be none the wiser constructing his Millennium Falcon.

The impressively ghastly stages of putrefaction

The visibility captivates us, but the worst of oceanic plastic pollution operates on the unseen level—“unseen” for being distantly out of view, beneath the larger, more buoyant pieces that litter the surface field, and close to microscopic even if we could submerge and pierce the opaque volumes of seawater with our sight. The concept of intentional “notice” matters as well: There’s nothing less noticeable in our littered world than, for example, a perfectly visible plastic grocery bag caught by the handle on a stalk of dead grass at the side of a freeway, expanding and deflating with gusts of wind as trucks barrel past. The sun will cook it over time into friability, a rain will weight the tatters off the decaying grass and into the draining currents that will further disseminate the multiplying, self-winding spills like sloughed skin, never actually disintegrating, only becoming more and more granular as the fragments finally reach the ocean, ceasing their subdivision at a point at which they are almost invisible but no longer soluble, forever salting the food and water supplies of a planet with an evenly dispersed payload of toxicity.

Noticing the ubiquity of plastic is terrifying: the red cap of a Tabasco sauce bottle (signatures of branding), the yellow tab that cinches a bag around a loaf of bread (plastic used to manage the packaging physics of plastic), the interior panels of a commercial jet (the toxic flammability of which kills most passengers in survivable accidents), playground kits for children (designed to absorb energy and reduce the risk of concussion), the thermoplastic threads of polyester woven around biodegradable cotton in the average shirt (if metal orthodontia and titanium hips make us cyborgs, what does our plastic outer skin make us?). You begin to imagine that it’s growing like a rhizome, independent of human industry. I skid a chair back in a café, and a black plastic plug slips from one metal foot, put there to avoid scuffing the linoleum. I pick it up, and before reinserting it, I look at its stealthy form, its inconspicuous utility. To know that this worthless plug will outlast me is to know how profoundly quiet annihilation can be. Humans are perversely sublimating their fear of death through the virtual immortality of synthetic petroleum byproducts.

To know that this worthless plug will outlast me is to know how profoundly quiet annihilation can be.

TKM

For a while when we were in Oakland, I made my own yogurt overnight in a metal thermos, washed my hair with baking soda and conditioned it with cider vinegar, and used Everclear as cleaning spray. My mom took these as glaring signs of impending poverty wrought by Bohemian underemployment. It’s true that I’d left my teaching job, which had offered tenure and a pension, to freelance for nonprofits and learn to grow my own food. But the rituals held in common an avoidance of plastic, not economy—paper boxes and glass bottles with small plastic lids instead of all-plastic containers, recyclable plastic-coated milk cartons instead of often unrecyclable plastic tubs. I’d been reading Beth Terry’s blog and book of the same title, My Plastic-Free Life, replete with plastic-reducing hacks like the ones above, and more: Make your own energy bars! BYO bag, mug, takeout containers, metal straw, and utensils—all the time, because who knows when you might want a snack! Instead of plastic-encased deodorant, spritz your underarms with lemon juice or vinegar! Dental floss is typically made of plastic and/or “waxed” with it, so use plain cotton sewing thread instead!

If the goal is simply to raise awareness of our personal daily contact with plastic, then her tips are useful. As you noted, it’s dispiritingly, terrifyingly fucking everywhere all the time in everything we do, to the point that it undergirds our whole existence and becomes invisible, exponentially so in the post-WWII era: As of mid-2017, half of all plastic ever produced had been made since 2004, and only 9 percent got recycled. But conscious individuals jonesing for real plastic-wrapped Lärabars, packing around mountaineering mess kits, and sporting increasingly greasy hair, linty teeth, and citrus-tinged B.O. are not going to rid the world of the epidemic. I genuinely admire Terry’s commitment and everything she’s done to increase the profile of the issue, but to buy her book and follow it to the letter is to cultivate both obsession and despair. I agree with her that we should make as many anti-plastic consumer choices as we reasonably can, but doing so in itself will not to save us, and unless we recognize that, we’re simply nurturing a quasi-religious guilt when we inevitably contribute to the tidal wave of waste. Like every other topic we’ve tackled, this one is a systemic issue and requires structural change through legislation, not simply voluntary consumer choice.

Plastic is not only a blight on the landscape or a danger to wildlife—it’s also a scourge to human health. The toxic soup we’ve made of the oceans is concentrated by fish and consumed by humans. There is increasing incidence of hypospadias—a disorder in which male infants are born with a splayed-open penis because the urethra is along the shaft instead of the tip—and prenatal exposure to estrogenic endocrine disrupters, such as bisphenol-A (BPA) in plastic, has been implicated in this rise. In the documentary FLOW (2008), a lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council explains that a single official is charged with regulating bottled water for all of the U.S., in addition to other responsibilities. Bottled water falls under FDA rules rather than the EPA’s more stringent Safe Drinking Water Act, and in this essentially unmonitored industry, a company was able to bottle and sell water pumped from next to a superfund site. The bottles leach BPA and other chemicals into the water they hold, which may also contain everything from rocket fuel to pathogenic bacteria—at a cost more than 2,200 times greater per gallon than tap water. Global expenditures on bottled water are about three times higher than what the U.N. estimates it would cost to ensure clean, safe drinking water for the entire world (38:13).

A scourge to human health

Given these facts, it seems unfathomable that we haven’t already passed a federal ban on plastic except in cases where no replacement has been invented, such as certain medical and transportation applications. Glass, cardboard, aluminum, natural textiles, and waxed paper are all recyclable or biodegradable and can stand in for plastic in a multitude of instances. But somehow, we haven’t even taken such measures to address the lowest-hanging fruit: the disposable plastic bags you conjure breathing in the highway breeze. Each one is used for an average of 12 minutes and then takes a millennium to break down—90 percent are not recycled. How do we have so much time and political will to devote to, for example, women’s reproductive choices—and so little to protecting all of humanity from genital-deforming disorders and cancers wrought by completely replaceable modes of carrying takeout and groceries? Plastic bags used in the U.S. alone require approximately 12 million barrels of oil annually to produce, revealing the one-two punch of carbon footprint and environmental toxicity as well as the close relationship between the juggernaut fossil fuel and plastic lobbies, so far stymieing more than a smattering of local bans. Many states in the Midwest have even passed preemptive measures prohibiting municipal restrictions.

A Plastic Ocean presents one of the few rays of hope for transmuting our existing masses of discarded plastic: plasma gasification, a technique pioneered by companies like PyroGenesis and already in use on the U.S.S. Gerald R. Ford and in a few locations in Asia. In essence, extremely high heat turns solid waste of various kinds into a gas that can been used for energy production, while reducing remaining materials to a small amount of inert slag that could potentially be used for building materials (and in any case will not photodegrade into gut shrapnel for baby birds). Other projects are planned in the U.K., but many more around the world have been started and shuttered before they could get off the ground. This probably says more about the existing stranglehold of fossil fuel subsidies than it does about the viability of the technology.

Gut shrapnel for baby birds

Boyan Slat, a Dutch inventor/social entrepreneur in his early 20s, started a nonprofit called The Ocean Cleanup that plans to launch multiple floating arrays in the Pacific garbage patch later this year, with the intent of using ocean currents to collect floating plastic for removal—though as we’ve noted, the more concerning and insidious pieces are suspended below the surface. His plan is Silicon Valley sexy because it’s new—his TEDx talk about the concept in 2012, when he was only 17, went viral—but it’s expensive and untested in the extreme weather conditions of the open ocean. Meanwhile, longtime nonprofit advocacy group The Ocean Conservancy continues to pursue old-school beach cleanups, which have collected hundreds of millions of pounds of trash that otherwise could have ended up in the water.

When I read about global warming and other environmental catastrophes in Weekly Reader as a kid, I was terrified. I asked my mom if we were all going to die, and she said not to worry—someone would invent a solution before that happened. Does she still believe that as she puts her leftover pizza slices in a disposable plastic freezer bag? Does your father when he cracks open an Arrowhead mini-bottle of BPA-laced water? Or maybe she thinks it’s too late and he figures he’ll be gone before we’re really in crisis. It can be hard to retain faith in the importance of one’s individual choices upon the realization that most “plastic-free” products, food items, and the like were shipped on giant plastic-wrapped pallets, passed through buildings constructed behind scaffolding stretched with plastic sheeting flapping in the wind. Easier, then, and less emotionally taxing in the short term, to dissociate from our choices and actions, to believe with all the zeal of a convert that a technocrat messiah will come.

But inventing interesting things that in theory might help is not the same as working with or even understanding the Earth, a system no humans could devise in their most manic prototyping and that would wordlessly heal itself if we gave it half a chance. In This Changes Everything, Naomi Klein writes at length about what she calls “the Geoclique,” a group of aspiring geoengineers out to solve problems like climate change with one big wave of the tech wand, rather than by addressing the unresolved issue that got us here—our dependence on fossil fuel and petroleum products:

[T]he Geoclique is crammed with overconfident men prone to complimenting each other on their fearsome brainpower. At one end you have Bill Gates, the movement’s sugar daddy, who once remarked that it was difficult for him to decide which was more important, his work on computer software or inoculations, because they both rank “right up there with the printing press and fire.” At the other end is Russ George, the U.S. entrepreneur who has been labeled a “rogue geoengineer” for dumping some one hundred tons of iron sulfate off the coast of British Columbia in 2012 [without government permission, in an attempt to encourage biomass growth to sequester ocean-acidifying carbon dioxide].

It also includes Richard Branson, whose fleets of Virgin airplanes still run on the climate-changing sludge of ancient swamps. Another idea championed by this group is “sun shielding”—injecting sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere to reflect back sunlight, theoretically reducing the greenhouse effect—a plan whose projected side effects range from turning the sky green to exacerbating drought and famine in Africa. Better to cease the monsoons than invent viable green alternatives to conventional air travel.

“Right up there with the printing press and fire”

Facing the challenges of plastic and fresh water, we are left with similar decisions: Stop using what we know is toxic and clean up what already exists, employing methods that are minimally damaging to ecosystems—or keep using it and wait for The Big Fix, as yet uninvented and untested. Devise water management systems that start from premises of public right, equity, and transparency—or allow private individuals to amass control over and set prices for a substance essential to survival, perpetuating war and occupation, on a 21st century scale that makes the Milagro beanfield developer look altruistic. The more irreparably we destroy the natural balance of the planet, the more we set the stage for billionaire-backed ventures to insist that we must try risky propositions whose side effects could be worse than the original problem. Compared to injecting irretrievable particles into the atmosphere, Slat’s ocean cleanup arrays seem lo-fi and conservative. I hope he comes back to find them filled with plastic he will then safely recycle or gasify, not teeming with the trapped bodies of migrating endangered sea turtles or demonstrating some other unpredicted damage. The project charges ahead, so I guess we’ll see.

GCG

“For as any speaker of French notices, styrène rhymes with sirène and proposes the collaboration of Resnais and Queneau as a contemporary song of the sirens. Its mermaids—the consumer products and industrial objects in the newly emerging culture of plastics in 1950s France—beckoned to both men with irresistible charm.”

—Edward Dimendberg

Technocrats adhere to the buzz that drums up investment capital. They are not dedicated to environmentalism without a monetary benefit and a personal heroic narrative that valorizes their work. “Stop using plastic for cheap disposable goods” is so mundane, a perfectly dull, workable solution that is anathema to venture capitalism and—in the short run—profitless; it’s so much cooler to build a Boyan Slat watercraft resembling a Romulan starship (and probably made mostly of plastics) that can initiate another waste management industry, which would then, of course, only encourage plastic production in order to underwrite Slat’s vision and enrich his shareholders. He needs a permanent raison d’être if he intends to remain viable. Keep fucking shit up so we can enable technological advances that can bask in the consequences of fucking shit up.

“Its mermaids beckoned to both men with irresistible charm.”

Could Slat just as easily have been a young innovator in seabed mining, deluding himself that out of sight = out of mind = magically clean and safe? Michael Johnston—CEO of the Canadian-based, Russian- and Omani-owned Nautilus Minerals—secured mining rights to the Solwara 1 deposit on the sea floor within Papua New Guinea’s territorial waters. He dresses up this new “invisible” site of ore extraction with reassurances of low environmental impact and tremendous financial gain for the people of PNG (the government has a 15% share in the enterprise). But what really insulates him from criticism is the fact that—like microplastic pollution—the damage occurs in a seemingly discrete submarine world (albeit in the shallower regions of the Bismarck Sea). No longer an unsightly mining operation exposed to the air! Perhaps a derrick or two will dot the horizon miles off the eastern coast of the country, but, otherwise, who would know? Would the massive plumes of sediment disturbed by the excavators create an uninhabitable murk for marine life? Who can say? Thus far, there have been no independent studies to explore the environmental impact of this relatively new process, nor a contingency plan forthcoming from Nautilus to manage that impact.

Of course, Johnston has nothing but respect for individuals in PNG (never mind international organizations) who might object to the plans: “You always get one or two people who jump up and down. Some people think if they make a lot of noise, they’ll be given money to go away, and we don’t do that.” (This trivializing rhetoric, of course, is unsettlingly reminiscent of what misogynist critics have said against accusers during the spate of recent sexual harassment allegations in the U.S. It could also be, in this case, a sign of a wealthy industrialist’s psychotic failure of imagination: “What else could an opponent possibly want but money?”)

The temporal long view is global capitalism’s encounter with the sublime; the sluice gates of production and the open maw of consumption simply can’t envision the contours and edges of a not-so-distant future when their own viaducts are bone dry. Fiscal quarters and clusters of disposable income mark the limits of acknowledged time and space; if there is an impoverished family on a remote island using toxic plastic garbage to ignite their cooking fires because there is no other affordable fuel, that is outside the boundaries of the market, at best a sordid anecdote, but never a signal of what is to come. An exhausted end to late capitalism alternately terrifies and exhilarates “free market” advocates, like privileged Shelley dumbfounded before Mont Blanc, the overwhelming evidence kept vaguely legendary as these opponents of conservation counteract their own nagging fears with shrugging fatalism, atrophic complacency, self-aggrandizing individualism, and the blind conviction that resistance is partisan bias. Extrapolated lines foretelling devastation become either fairy tales of the Rapture or the “propaganda” of the scientific method.

The sluice gates of production and the open maw of consumption

Plastic is no longer enchantingly visible; it is the dull carapace of our quotidian lives. But there was a time when it swayed before our eyes like colorful anemones, urchins, and coral, promising vividly colored convenience and luster without consequence. Bakelite—the original synthetic plastic—is now collectible, its relics still luminous as hard candy, conjuring an era when the alchemy of phenol and formaldehyde produced opalescent jewelry, black telephones with Art Deco curves, tortoiseshell radio cabinets, and jade- and ivory-colored mahjong tiles. When different processes and polymers emerged in the 1950s and ’60s—polyester, polypropylene, Kevlar—it still seemed fresh, cost-effective, and benign. Alain Resnais’s Le Chant du Styrène—a gently ironic ode to plastic commissioned by the French manufacturer Pechiney in 1958—traces the origins of plastic to its petrol-based amniotic fluid, displaying at first bright ganglions of colorful stems with unknown utility, wagging back and forth like flowers dancing in a Disney cartoon. Plastic as proto–Pop Art: Get ready for blood-red vinyl diner booths and black latex fetish outfits—looking wet without being wet, the false gloss of nostalgia and displaced eroticism, encasing the entropic organic reality of our own lives with pure sheen. But first, Raymond Queneau’s alexandrine text recited over Resnais’s imagery relates an impossible feat—returning plastic to its chemical sources, undoing the damage of synthesis with six feet per line:

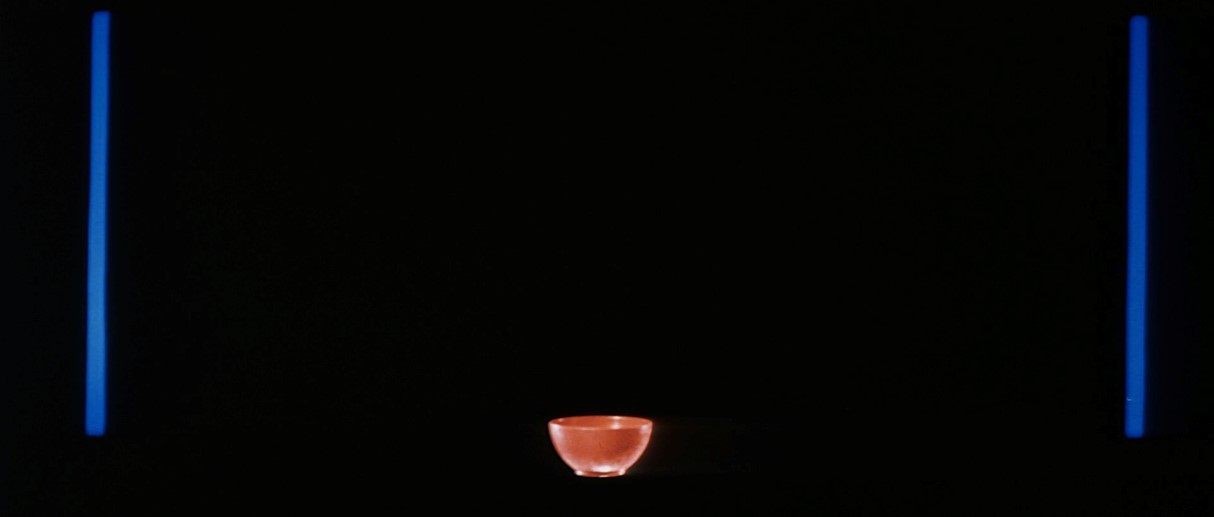

O temps, suspends ton bol, ô matière plastique !

D’où viens-tu ? Qui es-tu ? et qu’est-ce qui explique

Tes rares qualités ? De quoi es-tu donc fait ?

Quelle est son origine ?

I want him to look forward: This Grecian urn is a token of disease and indifference.

“O temps, suspends ton bol !”

Screenshots taken from Le Chant du Styrène (1958) are included here under principles of fair use for the purpose of commentary. This conversation is the seventh in an occasional series on films with environmental, food, and social justice themes. Previous installments have tackled protest, the (climate) apocalypse, the meat industry, dams, gleaning, and the globalized food system.

Work Cited:

Dimendberg, Edward. “‘These are not exercises in style’: Le Chant du Styrène,” October 112, Spring 2005, pp. 63–88.

About the Authors:

Teresa K. Miller is the author of sped (Sidebrow), co-editor of Food First: Selected Writings from 40 Years of Movement Building, and a graduate of the Mills College MFA program. Excerpts from her most recent full-length manuscript, a 2017 National Poetry Series finalist titled California Building, have appeared or are forthcoming in Berfrois, Crab Creek Review, Empty Mirror, Flag + Void, Fourteen Hills, Poor Claudia’s Phenome, and sparkle + blink.

Gregory Giles is a graduate of the Mills College MA program and founder of the once and future freak-pop band 20 Minute Loop, whose LP Songs Praising the Mutant Race was released in February 2017.