As the Ars team convenes for two days of meetings in Chicago, we're reaching back into the past to bring you some of our favorite articles from years gone by. This feature originally ran in December 2009.

It was 1879, and investor Charles A. Sumner sat at his desk, frustration pouring onto the page through his ink pen. Sumner, business partner to the radical economist and journalist Henry George, was finishing the concluding passages of a book about what had happened to the telegraph, or the Victorian Internet, as one historian calls it.

"This glorious invention was vouchsafed to mankind," he wrote, "that we might salute and converse with one another respectively stationed at remote and isolated points for a nominal sum."

But instead, he continued, "A wicked monopoly has seized hold of this beneficent capacity and design, and made it tributary, by exorbitant tariffs, to a most miserly and despicable greed."

It's a largely forgotten story, but one that still has relevance today. If you follow debates about broadband policy, you know that there are two perspectives perennially at war with each other. One seeks some regulation of the dominant industries and service providers of our time. The other seeks carte blanche for the private sector to do as it sees fit. Nowhere does the latter camp press this case harder than when it comes to network neutrality on the Internet, and appeals to the Founding Fathers aren't unknown.

"Our founding fathers understood that it is government that takes away people's freedoms, not individuals or companies," wrote entrepreneur Scott Cleland in an opinion piece for National Public Radio not long ago. Cleland opposes the Federal Communications Commission's proposals to codify into rules its principles prohibiting ISPs from discriminating against certain applications.

"At the core, the FCC's proposed pre-emptive 'net neutrality' regulations to preserve an 'open Internet' are not at all about promoting freedom but exactly the opposite. Freedom is not a zero sum game, where taking it away from some gives more to others. Taking away freedoms of some takes away freedom from all."

Reading this argument, one wonders if there ever was an age when the hands-off school of regulation got exactly what it seems to want—a network environment largely untarnished by public oversight.

In fact, there was such a time.

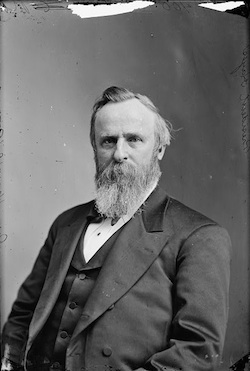

Hayessociated Press

Three years before Sumner wrote his lament, the country was wracked by the most convulsive presidential election since the outbreak of the Civil War: Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York versus Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio. The Republican party had split between loyalists to the administration of Ulysses S. Grant and those appalled by its corruption. In truth, the resurgent Democrats were no better when it came to civic virtue, but they lured some Republicans away with Tilden, who famously battled bribery and graft as governor of New York.

When, on that November night in 1876, the popular results indicated a narrow majority for the reform candidate, many assumed the first Democratic victory in two decades. But not so at one of the Associated Press's most prestigious affiliates, the ardently pro-Republican New York Times. When prominent Democrats nervously contacted the Times asking for an update on the results, its managing editor John Reid realized that the election was still in doubt. He contacted top Republican party officials and had them spread the word via telegram—the electoral college votes in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were still in play.

It was easy for these men to access the telegraph system, because its main operator, Western Union, was also militantly pro-Republican. During the long controversy in Congress over who actually won the districts in the disputed election of 1876, Western Union secretly siphoned to AP's general agent Henry Nash Smith the telegraph correspondence of key Democrats during the struggle. Smith, in turn, relayed this intelligence to the Hayes camp with instructions on how to proceed. On top of that, AP constantly published propaganda supporting the Republican side of the story. Meanwhile, Western Union insisted that it kept "all messages whatsoever . . . strictly private and confidential."

Tilden supporters weren't fooled. By the end of the debacle—Hayes having won the White House—they called AP "Hayessociated Press."

The great giveaway

It was no secret why Western Union sided with Republicans. By the 1870s, the Party of Lincoln (Abe himself being a former railroad lawyer) had given away massive quantities of land for the construction of railroads and telegraphs: almost 130 million acres (about seven percent of the continental United States) was granted to eighty enterprises. Although the telegraph had been pioneered by Samuel Morse in the 1840s, the innovation didn't really take off, economically speaking, until it partnered with the railroads, at which point it became the Victorian era's version of our information superhighway.

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 sped up the construction of a coast-to-coast railroad system, and it further subsidized telegraph growth as well. But Congress provided very little regulation or oversight for the largesse.

The result was the infamous Credit Mobilier scandal of the 1870s, a scheme that bears some resemblance to the Enron debacle of 2001. Rather than license the construction of the Union Pacific railroad to an independent contractor, its Board of Directors farmed the work out to Credit Mobilier, a company that was, essentially, themselves. In turn, Credit billed the UP vastly more than the actual cost of the project. To keep Congress quiet about the affair, the firm offered stock in itself to Representatives and Senators of any political persuasion at bargain basement prices.

In this context, it should come as no surprise that the nation's telegraph system quickly fell into the hands of one of the most notorious schemers of the Gilded Age.

reader comments

167