Mirror With Self-portrait

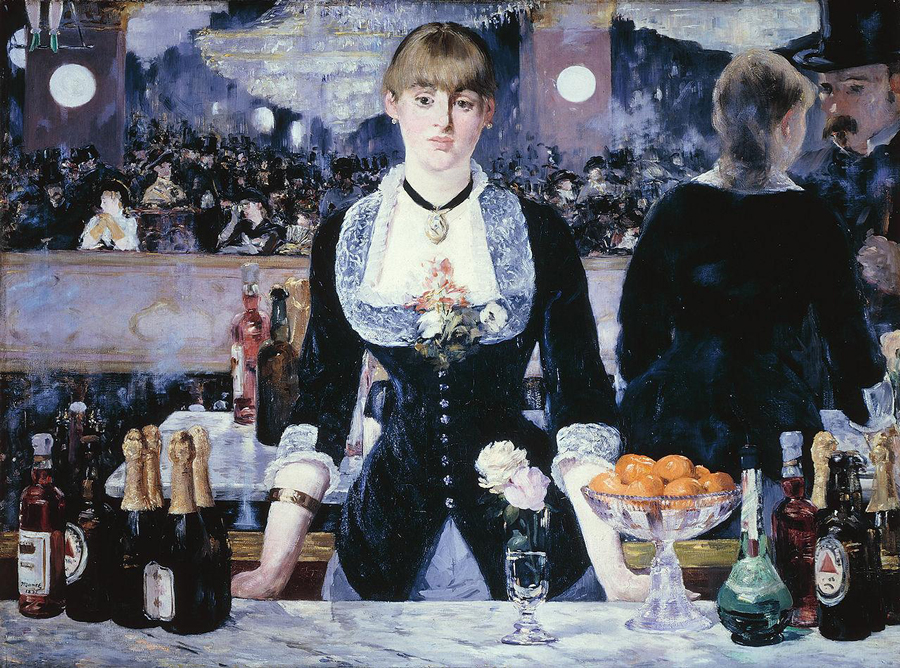

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Eduard Manet, 1882

by Jimmy Chen

In Eduard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) a woman bartender stands directly in front of us behind a bar, her hands confidently propped up — less obsequious than merely resigned, almost bored by the present narrative — ready to serve the customer, who is not only always right, but in this case on the right. I invoke the collective first “us” because, though we experience this painting alone, locked behind different POVs and angles, we do so collectively. Despite various media in which the painting is seen, be it “real life” or in books, or online, past generations, we are bound to a singular narrative: it is I about to order a drink. But who am I?

We can see the edge of the bar — as reflected in a mirror behind the bartender, which spans the majority of the canvas itself, like a painting within one — being perfectly parallel to the edge of the painting, meaning we are looking at the mirror head on; that the woman is standing directly in front of me (or you) would suggest that her head would eclipse one’s reflection of themselves in said mirror. And so, it would seem, who I am (or we are) shall be left to the imagination inside our heads. But there is a problem. On the right side of the painting, impossibly inside the theoretically parallel mirror, in clear view yet somehow subconsciously hidden to most people, a man faces the bartender. He would be me (or you).

What makes for a little fun art anecdote today was an obscene mechanical mistake in human perception. The renaissance worked hard to get the vanishing points right, and now this. Since then, or let us say because of then, painting was to become beholden to what one wanted to see in it. Images supplanted by projections, which leads us to Rene Magritte’s Not to Be Reproduced (1937), of a man standing in front of a mirror with his back to us — its perfect duplicate à la the Droste effect as some anti‐reflection inside the mirror. It is unclear whether the viewer is being ignored by the subject of the painting, the man, or if the subject of the painting, this man, is being ignored by himself. Such ingrown concern and existential conceit was fated towards redundancy, like a hallway of mirrors full of perfect doppelgangers.

Not to be Reproduced, Rene Magritte, 1937

Enter the selfie, whose mirror is demoted to what it actually is: a literal surface which reflects anything in front of it. And yet, as incidental the image is, we seek something under the surface. The mirror was actually first called a “looking glass,” which says less about its reflective capacity than the metaphysical act of looking; the potential of finding a better person inside. Yet, from Brothers Grimm to Oscar Wilde — whose deluded narcissists all eventually succumb to their image — literature hints that there may be nothing but ugliness to be found inside, or at least some foul truth after which painters like Rembrandt and Van Gogh sought in their self-portraits. Andy Warhol sneers at this idea, brandishing his tri-pod, as if exposing the artifice of the moment, the conceit of Self as one’s subject. So if vanity is ephemeral, it probably should be disseminated that way on Instagram — whose “insta,” in relation to instant gratification is not exactly a stretch here. Hospital and funeral selfies enable a histrionic generation so consumed by the presumed historicity of their very lives, that their experiences seem unreal—perhaps even non-experienced, as in a dream — until corroborated by likes. (Yes, Grandma died. You were there.) The mirror’s capacity in representation now flattened into a bio or booty pic, from the metaphysical to the literal.

One wonders if the first selfie was not Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434), of an Italian merchant and his wife in their home, wherein, on the wall behind the subjects, a curved mirror betrays — past the backs of the subjects, tiny and haunting—the painter himself. No more than a few brush marks, van Eyck stands there at the ultimate center of the work. Something similar occurs in Las Meninas (1656), only the mirror in the back of the painting shows the subjects (the King of Spain and his wife) posing for the very portrait whose canvas’ edge is seen in the actual painting itself. Velazquez was less abashed, allocating a good third of the canvas to himself.

Mirror, Grey, Gerhard Richter, 1991

It may have been Gerhard Richter who prophetically invited our mirror’s fate in his sardonic, or at least confrontational, mirror series (Spiegel, c. ‘90s), for which he painted glass so dark and flat that they had no way of conventionally functioning as paintings, only as mirrors. If the ultimate subject of every painting were its patron, let it reflect solely them. The problem was photographing the painting (for exhibition press, catalogs, etc.) without it incidentally betraying the photographer. Richter’s studio could only take pictures of the paintings from an angle, as if the problem Manet introduced more than a hundred years ago — of not so much who we were, but why we were there — was still abound. The eternal man waiting at the bar.

Craigslist Mirrors (2014) is a collection of photographs taken from Craigslist ads, whose amateur photographers (and hopeful sellers) would occasionally wind up — completely non-conceptually, in a free-market lowbrow pit — inside their ads in a kind of inadvertent and most sincere selfie. Conversely, the more thoughtful or abashed would make great effort not to be in the photo, evasively angling the mirror’s reflection elsewhere. The physical paradox of capturing something innately built to capture you. It was here, in the democratic trenches of the internet, where Manet, Magritte, and Richter’s concerns would finally meet. There’s something surreal and economically sad about being reduced to selling a mirror, as if trading in one’s empirical legacy in front of it — of zits being popped, teeth being flossed, dresses being tried, a good cry — for a meager sum.

For we cannot see our eyes without mirror, we are “condemned to the repertoire of its images,” figures Roland Barthes, whose theatrical use of “repertoire” suggests something deceitful about mimesis, some oeuvre of trickery, as if the mirror didn’t so much reflect life but tell lies about it. This paradox of not being able to see the thing that sees is explored in Zen Koans as well. If art holds a mirror to life, what should happen if a mirror is held to a mirror?

Untitled, Craigslist Mirrors, 2014

There may be no solution to Manet’s original problem of where to stand, how to be, who to be. When a pet discovers their likeness for the first time, they flip out. Their brains were never told the story of who they were, and thus cannot grasp the thing in front of them. Only primates, dolphins, and oddly elephants can recognize themselves in a mirror, which is not to say that a dog or cat cannot recognize their reflection, only that they are not aware that such a reflection is them. They attribute their exact movements to an uncanny coincidence, of some omniscient of possessed being predicting their every move. The Lacanian “mirror stage” (stade du miroir) proposes that an infant, when first introduced to their reflection, will begin to see themselves as a thing in the world, a neutral object to be observed by others. This psychoanalytic epiphany inaugurates a kind of existential loneliness which is to follow, for it is then we are first disembodied from ourselves. The world is no longer the story of our omniscience, but a collection of unrelated movements weaved into an okay narrative about ourselves. Abstract and absurd, as orphaned images, we seek temporary repose in the looking glass. If only it would take a snapshot of time, our flat effigies safely laminated in the reticent commentary of what it might mean. A smile so forced, you can hear the cheese.

About the Author:

Jimmy Chen lives in San Francisco, where he is an administrator at a public health institution. His work has appeared in McSweeney’s, Diagram, The Lifted Brow, Galavant, among other places. You may find him at jimmychenchen.com.