The Land Below Water

An elderly couple who live alone, and were both injured during the floods, sit on the verandah, for their evening tea.

by Manik Sharma. Photographs by Gursharan Kaur Bhalla

On December 7, a couple of weeks after Chennai had witnessed its worst rains in a century, I boarded an MRTS train, in a state of inquiry, as what is the nearest to a bird’s eye view that I can afford. The train runs above ground and by some altitude at that. I could summon the strength of a meta-narrative here, and like the train, cut across reality with a choking sense of ungainliness.

A boy waits for his mid-day meal. For nearly one-and-a-half months schools were closed. Which meant no free meals for these poor children (a source of regular nutrition) for that time.

There was water in the streets, in the cemeteries, and pretty much everything I could catch a glimpse of. People sat on rooftops, on chairs pointed every which way with mobile phones in their hands raised to the sky in search for a signal. The lucky ones hung over scaffolding, talking with unchaste haste, already contagious to the people standing in expectation.

71-year-old Shanmugam rests his head in hands. He has two sons who can’t find work. And no money to feed them with.

Many peered from inside the train, with disconcerted looks and a profound sense of keenness, despite knowing the obvious. It was an experience like any other, pilfering a sense of eroticism from a landscape where contempt was, inevitable, yet unpromising in its virtue.

At the salt pans women get paid half of what men do. They have to level the dissolve with their feet, running the risk of skin diseases by absorption. Since the floods every woman has had to step into the pans to make money.

Of course Chennai had created its own flood. But even in the misadventures that we can’t help but perpetrate there is this unidiomatic simplicity of language, the directness of the experience itself that we can’t help but be thrilled at some point. It is very hollow a thought, perhaps, but so are the many mega-buildings that now crowd the city. The train itself, running over water-logged alleys, and flooded streets was an ironic reflection – both in reality and the metaphor that is anybody’s guess here.

At a primary school in one of the villages where boys are low in numbers because they are lead into the fields for work at an early age. The floods meant more enrollments for this year as their is no work left to do.

Having for the first time in my life, lived for eight days without power, a phone signal and a means to travel, I was forced to contemplate the ‘naturalness’ of human life altogether.

Two children stand atop a tractor, bemused by camera lenses around them. Not a single media or government crew had made it to this place so far.

That if all consequence of being human is unnatural – we are now valuated in carbon emissions rather than emotion – how valid would it be to discount loss of life where there is loss of material; man made material, so how can the two be separable any more, or more importantly, for how long? I realised the importance of a candle for the first time, but couldn’t find any.

Malnutrition, especially in the old, is a common sight. With the cash and food crop washed away in the floods. Things won’t improve anytime soon.

We ran out of clean drinking water, since all of it was filtered through appliances that run on electricity. Wherever attempts were made to restore power in the city, people were electrocuted and died on the spot. In a hospital nearby, 18 patients died in the ICU chambers because the generators ran out of diesel. People who died, most of them could not be cremated, because city morgues were underwater as well.

A boy after returning from school jumps past his tired mother. This too shall pass – maybe.

But to me, even at that point, the restriction of the element of the city is such, the failure of the ATM machines and the inability to render cash, was what aggrandized the impact of loss. I witnessed a two-hour-long queue for the only ATM that was functional in my area; and needless to say that image stuck the longest. That was unless I stepped out of Chennai in January, as part of a project to survey the fringes.

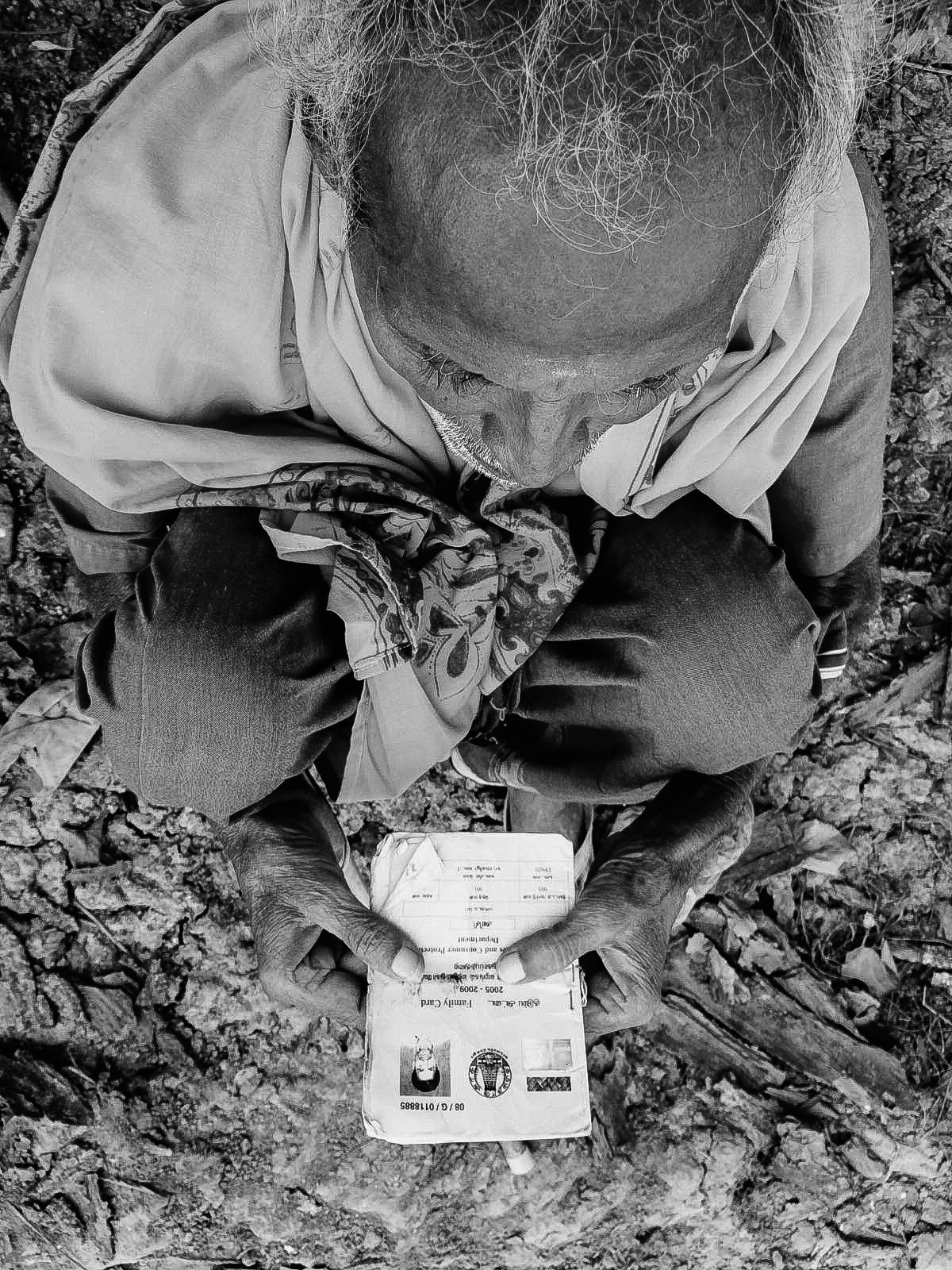

An old man sits with a ration card at a relief camp. While most of villagers are usually illiterate, they are not provided supplies without paperwork – paperwork they can’t even read let alone understand the importance of.

Of this land, little is known and will be known. The Tamil Nadu floods were the most expensive disaster of 2015; the most devastating flood of the year by far, anywhere in the world. Chennai, despite its many encumbrances as being its own worst enemy sauntered on. Outside though, the cuts hurt not for their depth, but their length and breadth.

Men work in a salt pan. The floods hit the pans as well, where the work hours are now double and it is conducive for production, that the workers perform when the sun is brightest.

Unlike the city, there is land here, and a living to be made off of it. So a flood scuppers that away. There are no second or third storeys to run to, no cards or bank accounts to fall back upon, and not even the MRTS train to nonchalantly partake in the auditory exercise of a disaster that felt more painful at the far end of the vein, than it did close to the heart. Take for example, Shanmugam (man with his head in his hands). 71-years-old, he lost 4 acres of his cashew nut plantation in the floods. For two months he had not earned a penny and was on the cusp of contemplating begging to continue living.

A farmer considers the state of his banana plantation, ruined during the floods.

There are so many narratives, so many stories, that the meta can now go hide its tail under the crotch of an unused typewriter or I may be forced to step on it and cause it to yelp in pain. The kind of pain that is lost in our prideful belongings and the losses they remind us of – unknown to these to these lives.

In the villages of Cuddalore district, women mostly work as cashew nut breakers. Without any healthcare or precautions they run the risk of contracting skin and respiratory problems from a resin that the shell releases on breaking.

Any number of words can be used to write the stories of these faces, and maybe I should. The smallest lenses and the highest tripods will only look city-ward, basking in that sense of self-assumed importance. The heaviest words will be soaked in the shadow of the brick, and not the soil; because in Chennai, there isn’t any left. Where there is, there might not be too many lives to tell stories about. But there are a lot many more to save. These are some of them. And they have the look of land below water – it took a flood to remind me of that.

About the Author:

Manik Sharma is a freelance journalist and poet based in Shimla.