Most of us think of Shakespeare as an Elizabethan. It’s almost impossible not to. Try imagining Shakespeare in Love ending with a cameo appearance by Simon Russell Beale as King James rather than with Judi Dench’s Queen Elizabeth. But Shakespeare was as much a Jacobean writer as he was an Elizabethan one, and to forget that is to distort the trajectory of his career and play down the quite different set of challenges he faced in the decade following the death of Elizabeth in 1603.

With the accession of the King of Scots in that year, Shakespeare became not only a Jacobean playwright, but also, by royal command, a King’s Man, his company rebranded as one patronised by the monarch himself. Under Elizabeth, Shakespeare and his fellow players had typically performed at court two or three times a year. That would change under James, who summoned them to play 10 or more times annually. Along with his appointment as a King’s Man, Shakespeare also became a minor court functionary, a groom of the chamber, and was issued four and a half yards of red cloth to be fashioned into livery to be worn when fulfilling his new duties.

It wasn’t long before he was called to appear in this role, first perhaps as part of the royal procession when James toured his new capital in 1604, and again later that year when a peace treaty with Spain, England’s long-feared enemy, was negotiated in London. Records indicate that Shakespeare and his fellow players were called away from the Globe theatre for 18 consecutive days that August to attend upon the Spanish embassy at Somerset House. Who better to stand around and look important than England’s finest actors? What was lost in revenue – this was the profitable summer season at the Globe – may well have been compensated for by the unrivalled access to this sea change in English foreign policy. An unexpected bonus of the treaty was greater access to Spanish books, and in his now lost play Cardenio Shakespeare would join other English dramatists who mined Cervantes’ Don Quixote for their plots.

It was not only Shakespeare’s sources (he would now turn for inspiration more often to Montaigne and Plutarch than to his well-worn copies of Ovid and Holinshed) but also his subject matter that took a different turn after 1603. From Henry VI through to Hamlet, he had explored in play after play the problem of succession, especially the threat of civil strife or foreign invasion – not surprisingly, since this is what Elizabethans feared might follow the death of their childless monarch. And in the nine history plays he wrote in the 1590s he also relentlessly explored the nature of Englishness. All this would change with the accession of the King of Scots, who arrived from Edinburgh with a queen, a pair of princes and a princess in tow, quieting any concerns about his own succession. And even as James tried (without much success) to persuade his two kingdoms to consider themselves one British nation, the Jacobean Shakespeare’s interest shifted from Englishness to Britishness in plays as diverse as King Lear, Macbeth and Cymbeline.

The Elizabethan Shakespeare divided his time between playwriting, acting and composing lyric poetry. The Jacobean Shakespeare would stick to writing plays. By the time he became a King’s Man, Shakespeare’s days as a poet were in the past, including the hours he had spent (as Frances Meres put it in 1598) reciting his “sugared sonnets among his private friends”. By 1603, it is highly likely that he had stopped touring the countryside with his playing company when London’s playhouses were shuttered during outbreaks of plague. And at much the same time he probably decided to stop appearing on stage at the Globe (though as a royal servant it’s likely he participated in court productions), for there are no records after this of his performing in the public theatre.

You might expect, given what we now think of as Shakespeare’s Olympian status, that at this point in his career he would have become increasingly isolated from lesser playwrights. The opposite is true. One of the most surprising things about Shakespeare’s Jacobean years is the extent to which they were spent in collaboration with others, especially with up-and-coming young writers skilled in popular genres that were proving something of a stretch for him. In these years, he teamed up with Thomas Middleton, a master of sharp satire and gritty citizen comedy, in Timon of Athens, and with George Wilkins, whose opening acts of Pericles he apparently overhauled and finished. And at the close of his writing career he co-authored three plays with John Fletcher, another promising young writer who would succeed him as the principal playwright of the King’s Men. Together, the two crafted Henry VIII, The Two Noble Kinsmen and Cardenio.

Shakespeare’s Elizabethan years were spent writing plays meant to be staged at outdoor amphitheatres, including the Theatre, the Curtain and the Globe. These buildings were all similar in design, built to hold 2,000 or so playgoers from across the social spectrum. As a Jacobean playwright that would change, for after 1608 Shakespeare found himself writing not only for this cross-section of playgoers but also for a more exclusive audience at a small indoor playhouse inside the City walls at Blackfriars. His company left the Globe to perform there during the chilly winter months – and charged patrons six times as much to enter as they did at their outdoor theatre. The impact of this new venue on what Shakespeare subsequently wrote was profound.

Gone are fight scenes like the thrilling duel at the end of Hamlet. The cramped playing space at Blackfriars, framed by playgoers who paid for the privilege of sitting on stools on the edge of the stage, couldn’t comfortably accommodate swordfighting. And its performances had to be illuminated by shimmering candlelight. It’s hard to imagine, without the exciting possibilities of this intimate new venue, that Shakespeare would have created such atmospheric scenes as the one in The Winter’s Tale in which the statue of Hermione magically comes to life.

When the King’s Men took over from the children’s company that had previously performed at Blackfriars, they wisely retained the skilled musicians who had accompanied them. Not surprisingly, then, the plays that Shakespeare subsequently wrote included a great deal of music, some of the finer compositions the result of a different sort of collaboration, as Shakespeare teamed up with Robert Johnson, a talented lutenist and composer, in writing the lyrics for such memorable songs as Hark, hark the lark in Cymbeline, Get you hence in The Winter’s Tale, and Full fathom five and Where the bee sucks in The Tempest.

Largely gone from Shakespeare’s late Jacobean works are the trumpets and drums of his earlier plays, replaced by more subtle musical effects. You can hear it in Cymbeline’s call for “solemn music”, the “sad and solemn music” in Henry VIII, the “sudden twang of instruments” in The Two Noble Kinsmen, and especially in The Tempest, with its repeated calls for “solemn and strange music” and “soft music”. Formal dancing, too, began to figure regularly in his plays. While only six of his Elizabethan plays had included dancing scenes, after the move to Blackfriars dance becomes a regular feature of Shakespeare’s work.

For many modern readers and playgoers, and surely for his contemporaries as well, the most distinctive feature of Shakespeare’s Jacobean plays is their often difficult and knotty verse style. It could not have stood in sharper contrast to his earlier work, especially that of his lyric period, plays such as Romeo and Juliet defined by heavily end-stopped lines and extensive rhyme. Take for an example of this older style Benvolio’s witty banter with Romeo, as they enter together early on in that play. The speech’s highly formal ababcc rhyme scheme more closely resembles the final quatrain and couplet of a sonnet than it does ordinary conversation between two friends:

Tut, man, one fire burns out another’s burning,

One pain is lessened by another’s anguish;

Turn giddy, and be holp by backward turning;

One desperate grief cures with another’s languish:

Take thou some new infection to thy eye,

And the rank poison of the old will die.

It would have been impossible to predict that a decade or so later the author of these lines would be writing in so radically different – and, for many, so impenetrable – a style. Consider the brief and bewildering speech from the opening scene of Henry VIII in which Norfolk defends a seemingly hyperbolic description:

As I belong to worship, and affect

In honour, honesty, the tract of every thing,

Would by a good discourser lose some life,

Which action’s self was tongue to.

Even the most experienced editors throw up their hands in despair at passages like this. With patience, the sense of it can be unpacked. Norfolk has taken a very roundabout way of saying: “Look, I’m noble and bound to tell the truth; but no matter how well a skilled reporter can describe something, it would fall short of what those who were there experienced.” Frank Kermode put it as well as anyone when he spoke of “the muscle-bound contortions of the late Shakespeare’s language”.

The effects of this dense style would infuse the work with an edge rarely found in Shakespeare’s Elizabethan plays. Perhaps the most striking example is Leontes’ speech in The Winter’s Tale when he looks at his son Mamillius and convinces himself of Hermione’s infidelity:

Can thy dam, may’t be

Affection? Thy intention stabs the centre.

Thou do’st make possible things not so held,

Communicat’st with dreams (how can this be?)

With what’s unreal: thou coactive art,

And fellow’st nothing. Then ’tis very credent,

Thou may’st co-join with something, and thou do’st,

(And that beyond commission) and I find it,

(And that to the infection of my brains,

And hardening of my brows).

The fits and starts, parenthetical asides, elisions and self-interruptions convey a character in crisis. We don’t have to know exactly what Leontes is saying – and that’s the point – to know just what he is feeling or how frantically his mind is working. His friend Polixenes, who overhears this speech, speaks for many of us when he says: “What means Sicilia?” And Hermione adds: “He something seems unsettled.” It’s as if in their puzzled reactions Shakespeare is half-apologising to playgoers for writing lines that he knows we, too, find unintelligible – even as the speech wonderfully renders the maddened state of mind of a jealous man who persuades himself that he has been cuckolded by his best friend. After a quarter-century of playwriting, Shakespeare was still experimenting, still struggling with how best to capture a fevered mind at work.

In many of his Jacobean plays, Shakespeare seems obsessively drawn to scenes of almost unbearable emotional intensity. He seems to have learned to use extended moments of silence to ever greater effect. Examples come readily to mind, typically focused on a pair of characters: the death of Lear with Cordelia in his arms; Pericles reunited with and restored to life by his daughter Marina; Volumnia subduing (and sealing the fate of) her son Coriolanus; and Imogen waking up beside the headless corpse of the man she thinks to be her beloved Posthumus. Such scenes are visually arresting and so emotionally charged that many find them hard to watch. It may be coincidental, but in his Elizabethan days Shakespeare referred to playgoers as auditors, while in his Jacobean period he describes them as spectators. The shift from ear to eye may well reflect the extent to which he became more conscious of the ways in which he could reach playgoers not only through his mellifluous verse but also through powerful tableaux.

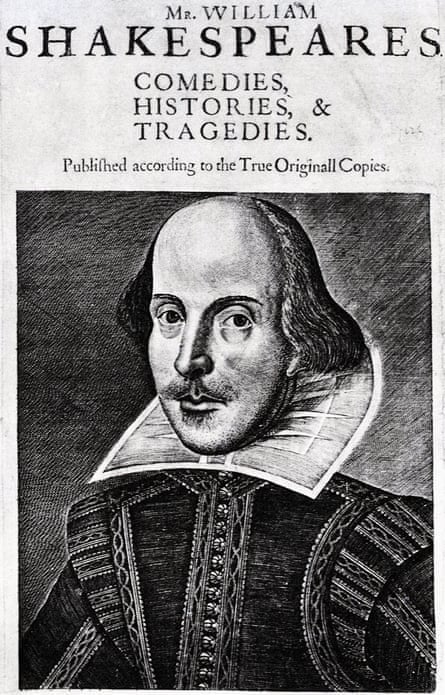

In 1623, a decade after Shakespeare retired and seven years after his death, the First Folio, a gathering of 36 of his plays, was published – half of them for the first time. One of the mysteries of Shakespeare’s career is the decision – we don’t know whether it was his or his company’s – to almost stop publishing his plays after he became a King’s Man. Of the plays written after 1603, only King Lear and the co-authored Pericles were published in his lifetime. So it was not until the Folio appeared that so many Jacobean masterpieces – Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, The Winter’s Tale, Coriolanus, Measure for Measure, All’s Well, Cymbeline, Timon of Athens, Henry VIII and The Tempest – could be read. It’s sobering to consider that if this volume had never been published, Shakespeare might be celebrated today as an almost exclusively Elizabethan playwright, his remarkable decade of work as a King’s Man all but lost to us.