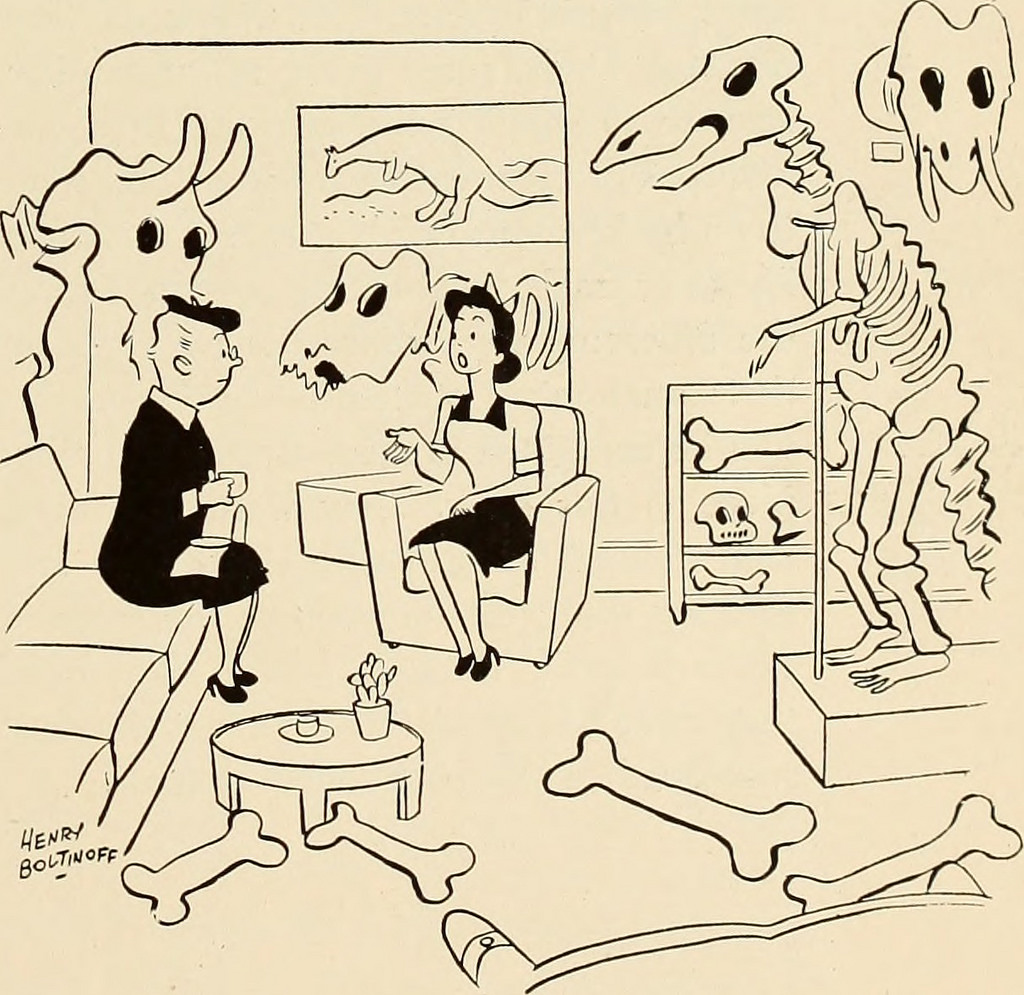

Everybody Draw the Dinosaur

Image from The dinosaur book: the ruling reptiles and their relatives, by Edwin H. Colbert and John C. Germann, 1945

From London Review of Books:

What colour was a Tyrannosaurus rex? How did an Archaeopteryx court a mate? And how do you paint the visual likeness of something no human eye will ever see? Far from bedevilling the artists who wanted to depict prehistoric creatures and their lost worlds, Zoë Lescaze’s book shows that such conundrums have in fact been invitations to glorious freedom. For nearly two hundred years the resulting genre – now known as palaeoart – has been a playground wherein tyrannosaurids, plesiosaurs and their fellows have not only illustrated scientific knowledge, but acted as scaled and feathered proxies for the anxieties of contemporary life. Lescaze argues that they should be seen as ‘roads to understanding our relationship to the past and our place within the present’. Despite these garish images of dinosaur combat and primeval cataclysm having held at best the status of kitsch, it is impossible to deny the extraordinary success of the genre. None of us has ever seen one, but who doesn’t know what a dinosaur looks like?

Palaeoart is inseparable from palaeontology, the scientific discipline it illuminates, and as interpretations of dinosaur anatomy and behaviour have changed, artists have generally tried to keep up with them. Debate still centres on how true to life it is possible to make representations of extinct creatures – how much soft tissue should they have? What colouration is plausible, given what we know about extant animal patterning? Historical palaeoartists typically incorporated the best knowledge of the time, so such questions can’t be completely ignored when looking at their work. But Lescaze deftly sidesteps this by making Palaeoart a history of images and artists, not a history of the accuracy of their art. Almost every image in the book became scientifically obsolete soon after it was created. ‘It is the imaginative nature of these works that makes them wonderful,’ Lescaze writes. ‘Rather than dismissing them as outdated, we should revel in their departures from reason.’

These images channel the spirit of their times and the character of their authors with a transparency their scientific pretension only underlines. Adorno wrote that the public’s fascination with dinosaurs was a ‘collective projection of the monstrous total state’ (‘people prepare themselves for its terrors by familiarising themselves with gigantic images’); keeping an eye on the wider historical context, Lescaze picks up on similar historical and psychological investments. Of the most widely repeated motif in 19th-century palaeoart – a plesiosaur and an ichthyosaur locked in deadly combat on the high seas – she observes that ‘the study of prehistoric marine reptiles began in the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, which were characterised by spectacular marine battles.’ In more surrealist mode, a painting by the Czech artist Zdeněk Burian showing a confrontation between a plated and spiked stegosaurian and a surprised-looking Antrodemus is given a psychological reading: ‘Violent arguments between Burian’s parents marred his childhood,’ Lescaze writes, transforming the prehistoric antagonists into monstrous grown-ups.

Images of violent combat between different prehistoric species are a constant in palaeoart.

“Feathered, Furred or Coloured”, Francis Gooding, London Review of Books