Rave as Ecology: Plugging In

CXEMA Rave, Kiev, Ukraine

by Charlie Mills

In 2011, Urbanomic published Fanged Noumena, a collection of writings from influential British philosopher turned NRx posterboy Nick Land. Along with writers such as Sadie Plant and Kodwo Eshun, Land had spent the 1990s in Britain traversing a hysteria of alienating forces, from the further onslaught of neoliberal capital to the emergent roles of algorithmic technologies and cyberspace. Given this climate, he was no stranger to the ruthless affectivity of electronic music and rave culture in expressing these social tendencies, following its descent into the darker techno derivatives of what Simon Reynolds called the ’90s “hardcore continuum”, a sonic wormhole stretching from Doomcore to Jungle to Gabber.

For Land, raving was a lucid expression of our nascent posthumanism, a place where identity fractured as we came to embody new cybernetic pleasures. It is for this reason that in one of two epigraphs introducing Land’s texts, the late Mark Fisher quotes his little known essay, ‘”No Future”, an ode to the intensities of ’90s techno-culture. Along with Land, Fisher recognised rave music’s inherent necro-libidinal charge; its ability to express wider cultural forces. He quotes, rave was our “impending human extinction becoming accessible as a dancefloor.”[1]

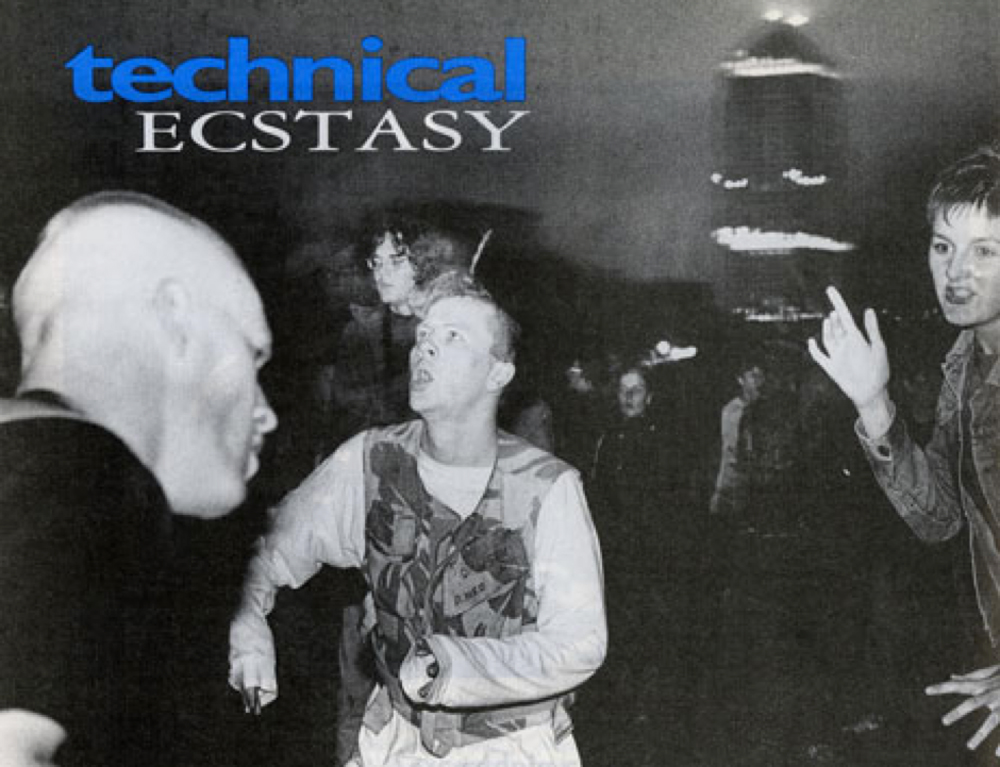

For the past five years or so I have watched this psychic extinction play out. Every weekend, thousands continue to cram into derelict warehouses, mildew archways and fetid cauldrons. All hellbent on chemical highs and loops of acidic bass. Bodies are carved out of the dark terrain by schizophrenic lasers, their movements pulsing through dense smoke like military optics laced with amphetamine. Catatonic stares and abject grins aligned toward the fortified DJ booth, its messianic presence infusing each dancer with a sermonic frenzy. Given its darker side it isn’t hard to see the apocalyptic edge of raving. Crowds of half-vacant minds and wonky irises; anaemic thoughts chewed up like pulp.

Raves and rave culture are for many a pristine example of contemporary escapism. Where the young go to ‘get away’ from the responsibilities of daily life or the onslaught of social alienation; burying their heads in the warm bosom of synthetic drum kits and modular FX. A collective orgasm mixed with wild entropy. For some this is just another sordid example of a generation gone completely wrong; living for the weekend, albeit with a uniquely dystopian edge; the latest wave of youth to be sucked into the hypnotic prism of low frequencies, dry mouths and euphoric highs. In this case, raves are not simply a dystopia in waiting but a real time eschatology; a hyperstition of full-blown planetary meltdown.

None of this is new of course. Raves are the latest in a long history of Dionysiac spaces. From the Epicurean Garden to the salons and clubs of French libertines. In aesthetics too, from Athenian tragedies to Mikhail Bakhtin’s analysis of Medieval carnival, even Nietzsche’s Wagner before he ‘crept back to the cross’. These were and still are spaces where social codes dissolve under the dual glow of moral skepticism and hedonistic pleasure. Places where mutual trust and collective anonymity help engender joyful acts of social transgression. ‘Losing oneself’ in a swarm of like-minded clubbers, the prosaic gestures of shared water and gum establishing a subtle aura of communistic good will from which to freely express one’s self.

What’s interesting to me, however, is the assumption of escape. That raves and rave music are about experiencing something exterior. Something outside of the banal platitudes of humdrum ‘reality’. For in this sense, is it not antithetical then to assert the ‘accessibility’ of posthuman dissolution, through what could be translated as a mode of experiential withdrawal? To withdraw and access in the same movement?

This could have been true of rock. In so far as the gig or the stadium concert was an imaginary experience filtered through autobiographical or social realist criticism; pre-defined stories waiting to be interpreted by the listener. Particular to the ’90s, Fisher was a keen critic of the “reactionary pantomime of Britpop”,[2] which by establishing a monolithic identity of white British culture ignored what was new and exciting about the decade: cultural pluralism, accelerating technology and genre hybridity. As Reynolds attests, the anxiety-curing swagger of faux British chauvinism – whether or not to see Oasis or Blur at Glastonbury ‘94 – was not translatable to the basic principles of rave’s enthralled dance floors. Instead of receding into the carceral identities of monoethnic Britain, raving was a process of creating something new.

For its followers, the appeal of rave’s lucent strobes, dark atmospheres and crystal drips was not to be found in typical forms of aesthetic consumption. For those on the inside, the revolutionary potential lied in the fact that “rave constructs an experience.”[3]

In this sense raves are in fact machines; or what Deleuze and Guattari would call a ‘desiring-machine’. They are an integrated system of technology and labour which produces experience. Rave’s dance floor is an assemblage of psychological, chemical, electronic and corporeal software, rigged up through neurons, electrons, chemicals and sound waves. A decentralised and nonhierarchical cybernetic system, melding technology, matter and affect into a horizontal flow of collective acceleration. Its function as an experience is like that of a factory, constructing intensities that each component plugs in and responds to: lights/wavelengths, drugs/hormones, clothes/textures, mixers/frequencies, dancers/bodies, “a continuous, self-vibrating region of intensities whose development avoids any orientation toward a culmination point or external end.”[4]

In a rave set acid synths are left to gargle into obscurity whilst relentless break-cuts fold endlessly back into themselves. Tracks evolve without narrative and emotions surge forth without aim; crescendos ascend to infinity and micro-sonic blips dissolve as quickly as they first appeared. Devoid of any clear determination each element is connected to a real-time feedback loop of continuous matter-energy, substituting a progressive and linear perception of time with a cyclic repetition of singular events; what Nietzsche would call the ‘eternal return’. A series of techno-somatic events that flows through you and into the next. Raves are sex without genitals, pleasure without climax. Dial in, jack up and get loose.

So where’s the escape? If anything, to me raving is about plugging into something extra. Something that is always more than one. The contemporary philosopher Timothy Morton would call this mode of perception ‘ecology’. The disintegration of anthropocentric boundaries between human and non-human, nature and culture; or the auxiliary dualisms of mind/body, inside/outside. Ontologically speaking, in our day-to-day experience of phenomena we usually run on this default setting: the banal plateau of Kantian epistemology. That there is something fundamentally different about us ‘in here’ and the world ‘out there’ – and that we will never access the world ‘in itself’. Being part of rave shatters this assumption.

Fully immersed on the dance floor, every raver comes to see themselves less as an isolated subject and more like a desiring-machine; a blend of human and non-human intensities, plugged into the different material registers of the rave. Bodies are no longer fleshy lumps of tissue and bone detached from the mind, they are portals. Wormholes to the prepersonal continuum of what Deleuze and Guattari call ‘The Body without Organs’ – an immanent plane of proto-subjective soup that connects a hand cocked liked a pistol to a Kenwood subwoofer, a rush of serotonin to the neon glow of a UV blacklight.

Cover Image for The Wire 300: Simon Reynolds on the Hardcore Continuum #1: Hardcore Rave (1992)

Even the most personal sensations are deindividuated, the almost telepathic level of empathy felt on Ecstasy are akin to what Richard Smith calls ‘a communism of the emotions.’ Piece by piece, mix by mix ravers are dissolved into an orgiastic sense of connectivity. To the sound, the space, the electricity. To each other. Soon it is hard to discern where ‘you’ start and where ‘they’ or ‘it’ ends. Electro-libidinal wires are crisscrossed and welded together. Currents of sonic energy and dopamine rerouted through neighbouring bodies and technical apparatus. “An oozy yearn, a bliss-ache, a trembley effervescence that makes you feel like you’ve got champagne for blood.”[5]

Raving is a spectral game. Objects of desire are replaced by liminal intensities; tempos devoured by pure speed. Whilst to some degree our ‘access’ to the experience of raving remains similar to other musical or quotidian events – after all, no one is denying Kant’s metaphysics of sense, albeit filtered through a Nietzschean body that is both eternal and different. The point is, it’s not really a question of our access at all. The beauty of raving, and the ecological aspect of its experience, is that you come to sense how you yourself are accessed. The neatly shrink-wrapped subjectivity that we all covet and protect almost floats around outside of you, endlessly warped and permeable to the collective flows of rave’s electro-chemical highs. For ravers, it becomes less a question of escaping reality, and more a drive to be accessed by reality. Frightened as we all are of the insidious poverty of our day-to-day sensations, a mode of being which is always-already once removed from the inherent multiplicity of posthuman becoming.

References:

[1] Nick Land, ‘No Future,’ in Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987 – 2007 (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2011) pp. 398.

[2] Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Winchester: Zero Books, 2014) pp. 40.

[3] Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash (London: Picador, 1998) pp. xix.

[4] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005) pp. 2.

[5] Renyolds, xxv.

About the Author:

Charlie Mills is a writer and postgraduate student at Goldsmiths College, London.