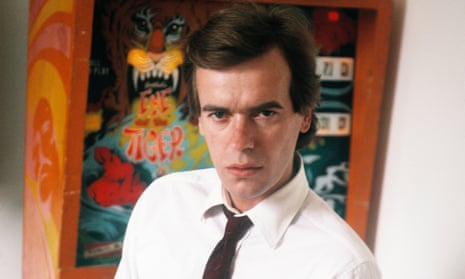

In 1982, already the author of four novels, Martin Amis published a fizzy, swaggering non-fiction book about arcade games. Soon out of print and expunged from his official bibliography ever since, it became a legendary text, fetching enormous second-hand prices and consulted tremblingly by an elite band of researchers in copyright libraries. Now, cheeringly, it’s no longer all that embarrassing to declare an intellectual interest in video games, so the book has been reissued. But is it a historical curio or something more?

In the first third of the book, Amis casts a hungry sociological eye over the now almost vanished culture of the arcades, gorgeously illustrated by large colour photographs. He tries out the neologism “vidkids” for their denizens, and slathers on the hyperbolic Project Fear. “The casualty wards of metropolitan hospitals are fighting an epidemic of colourful new maladies – Asteroid Elbow, PacMan Finger, Galaxian Spine, Centipede Disc,” he writes. “(God knows what this stuff is doing to our eyes.)” Amis tells stories of late-night game binges in London, and roaming the bars of Paris while smoking, drinking and playing arcade games – at one point, with a wingman who is almost certainly a Calvados-drenched Christopher Hitchens. Our author, indeed, adopts the persona of a street-hustling expert impatient with the theoretical pointy-heads. One writer says the flashing lights and beeps of the arcade are “womblike”, to which Amis retorts: “You wonder, what kind of womb did this guy grow up in?”

The middle section consists of mini-essays about individual games, oddly focused on tips for getting high scores. In Space Invaders, Amis sagely advises, you should concentrate on narrowing the phalanx of enemies so it takes longer to traverse the screen. (Very true.) In Pac-Man, meanwhile, you should be sparing in your use of “Wraparound Avenue”. (Also good advice.) Amis demonstrates fine taste, singling out as masterpieces of the form games such as Defender (“the most thrilling, sinister and tortuous yet devised”) and Tempest (“the least monstrous and most abstract game … a breakthrough”) that are still widely acknowledged as all-time classics.

In the book’s last third, he pads things out dutifully with a survey of “TV games” (early home consoles), handheld games, and even a couple of typed-out programs in Basic (supplied by others) for readers to enter into their computers at home. Some readers will feast on the retro tech porn, but this section is otherwise very much of its time – as is, unfortunately, the entry in the final glossary which explains that “faggot” means “gay”. (For the last entry, Amis is careful to signal that he still owns some unfrazzled highbrow synapses by alluding to Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire: “zembla – reformed video addict”.)

What furnishes the book’s lasting interest, inevitably, is its thematic relationship to the novels. Amis’s fictional nostalgie de la boue, his lust for lowlifes, informs this book as much as the subsequent Money, as he thrills reverse-snobbishly to the alleged brutishness of the arcades’ inhabitants: “These, then, are the punks, the blankies, the full generations of vandals and no-hopers we have been promised for so long.” Amis’s fiction, too, is marbled with game-playing – both formal (tennis, darts) and psychological – and, most relevantly here, with a sense of impending apocalypse.

The 1980s, after all, were the age of nuclear paranoia, which is the cognitive weather of much of Amis’s fiction, and was pictured most devastatingly in the arcade by the game Missile Command. This, you may remember, is an abstract, pastel-coloured simulation of intercontinental ballistic missile defence, in which the player uses a trackball and fire button to destroy incoming nukes in mid-air. This book has a brief preface by none other than Steven Spielberg, who is pictured leaning casually on a Missile Command arcade machine, and slyly emphasises his superiority to the author. “I have actually exceeded 500,000 at Missile Command,” Spielberg boasts, one-upping Amis, who confesses to achieving less than a tenth of that score.

Missile Command is a masterpiece of cognitive panic. As you progress, the nuclear missiles come in ever thicker and faster, and there is only ever one possible ending: your city is destroyed. It is, Amis writes, “an enigma, a mystery: one of the most beautiful and imaginative of all these curious games”. It is also more topical now than at any time since its release, in an age where a mockumentary-style novel about thermo-nuclear Armageddon (Jeffrey Lewis’s brilliant The 2020 Commission Report on the North Korean Nuclear Attacks Against the United States) can seem all too plausible as sober prediction. Never mind invaders from space; who is in command of the missiles?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion