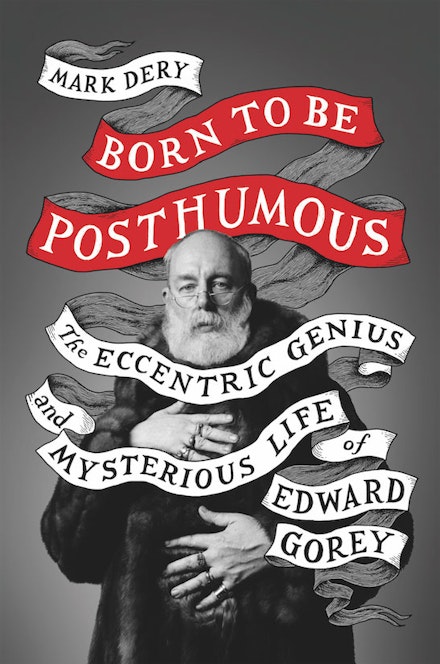

Art Books In Conversation

MARK DERY with Thyrza Nichols Goodeve

Mark Dery

Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey

(Little, Brown, 2018)

How does a deeply read, supremely pyrotechnic wordsmith, pioneer of cyberculturewho popularized culture jamming and first articulated the notion of Afrofuturism in his conversation with Samuel R. Delany (“Black to the Future” 1993)—scholar of glam rock, author of countless articles on gothic surrealism and natural-history gothic (see: “William Burroughs and Chilopodophobia”), and most trusted guide to zombies and the terror of clowns (see: “Dead Man Walking: What Do Zombies Mean?” 2010)—write a celebrated mainstream biography of the beloved and wildly complex Edward Gorey? Senior art editor Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, a follower of Dery’s work since the 1990s, sat down with him in November to answer just such a question. The result is the realization that Born to Be Posthumous—a labor of seven years—is not so much one book but many: a deeply researched biography, a stunning critical and visual analysis of Gorey’s books, theatrical forays, and Dadaist everyday life; a deep dive into the philosophical and aesthetic traditions from which Gorey’s own aesthetic is derived (surrealist, Victorian, modernist, camp macabre—even Heidegger makes many an appearance); and ultimately, a razor-sharp whirl through the impossible possible question of Gorey’s fabulously queer (a)sexuality.

***

Mark Dery: Let me ask you a question. What did you think of the narratorial voice?

Thyrza Nichols Goodeve (Rail): Reading about Gorey as a writer made me better understand where your writing comes from—your exacting vocabulary, linguistic wit, and campy brilliance. As to your narratorial voice, it was familiar as the erudite Dery without getting in the way of the biographical narrative if that’s what you were wondering. There are so many layers and really so many books in here.

Dery: I ask because I had to address a two, or multi, headed Barnumesque freak—on the one hand, I had to tell the story of a relatively “featureless” life, to use Gorey’s delicious adjective. Here is a man who, when he gave himself the Proust questionnaire for Vanity Fair, answered “What is your favorite journey?” with “Looking out the window.” How do you tell this story? You explore his psychic geography, but you also have to switch horses midstream, leap from being a biographer to an art historian and literary critic and when you’ve made short work of that you hit the pause button again and return to the storytelling. My great worry is whether switching like this gives the reader a kind of narrative indigestion.

Rail: Not at all, I think this narrative switching is precisely what makes the book so strong. It is your ability to cross genres from biography to criticism to social history to queer theory which allows you to write a biography of—what is the quote at the end—the story of Gorey as “the most one of a kind person you will ever meet.”

Dery: That’s Chris Seufert’s description. He shot the documentary of Gorey at the end of his life. To begin, Gorey was just preternaturally gifted—off the charts. He was an omnivorous, insatiable bibliomaniac and book worm. He started reading at age three and by age five he was reading Dracula and Frankenstein and by eight had read the collected works of Victor Hugo. He was obsessive—those pattern on pattern crosshatches that look like handmade engravings tell you that. By his seventies he’d read every Agatha Christie book countless times. He went to nearly every New York City Ballet for twenty three years—eight performances a week, thirty-nine performances of The Nutcracker. And he was also a phenomenal multi-tasker: I quote his friend Mel Schierman’s son Anthony, who stayed with Gorey at his home on the Cape in the ’80s and who described Gorey reading a novel a day while watching TV shows, knitting, and making stuffed animals, then going to the movies at night, eating out twice a day, and still finding time to do the drawings!

Rail: The section where you discuss how deeply traumatized he was by taking IQ tests in grade school was fascinating.

Dery: I wrote an essay in my last collection (I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts: Drive-By Essays on American Dread, American Dreams) about the agonies of the IQ test and how it deformed me as a child, which is true for Gorey as well. The principal of the Francis Parker School in Chicago, where he went, lived in the same building that housed something called the Human Engineering Laboratory, which devised intelligence tests. As a result, Gorey said, they took IQ tests every other week, practically. At one point later in his life, he asked his dear friend and collaborator Peter Neumeyer this painful, poignant question, “You are studying children’s education. Are there any studies of the effects of IQ tests on children?”

Rail: Was his childhood particularly traumatic?

Dery: I think we make a mistake if we make the classic Freudian psychobiographical move and look for the root of his aesthetic in bad toilet training or molestation by an ominous vicar. One of the points of my analysis is his aesthetic did derive in part from other aesthetics. That said, the family was pathologically peripatetic. No one knows what that was about, but they were moving constantly—all over Chicago, sometimes within a block or two. His father was a crime reporter before Ted was born, then during his childhood he was a publicist first for the Drake and the Blackstone hotels (where the phrase “smoke filled room” was coined) and that’s probably where Ted’s father met Corinna Mura, the faux-Latina cabaret singer of Casablanca fame (she sings “La Marseillaise”) who was briefly Ted’s stepmother. But another shadow is that Ted was quite close to his maternal grandfather—William Garvey, a telephone executive, who bundled his wife off to the loony bin. She claimed to have undergone shock treatment and was locked in a padded cell against her will and when you thumb through all of Gorey’s books for references to insane asylums, they’re everywhere. People are dragged off to the Weedhaven Laughing Academy and so forth. There’s just one reference after another. And then there is the Catholic Church and this mysterious period when Gorey was very briefly enrolled in Parochial school as a tot and something went wrong. He essentially dug in his heels and refused to go. He claims to have thrown up in church. They pulled him out of school and then his mother took him for whatever incalculable reason to live with his cousins in Florida for a school year. Given the Catholic church’s best-known franchise, predatory pedophilia, it’s certainly not beyond the realm of possibility that something untoward happened to him. He was a beautiful little boy with that androgynous look that brings out the worst in creepier men of the cloth. It seems telling that the clergy are only ever sinister in Gorey and that the Church of Rome always casts an ominous shadow. That said, there isn’t a scintilla of evidence to support such lurid speculations, so it’s important we underscore the point that they’re speculations only. Against them stands the recollections of close friends like his Harvard schoolmate Larry Osgood, who told me that whatever put Gorey off sex forever almost certainly happened in high school.

Rail: One of my favorite parts of your book is the discussion of his Harvard years, his formation against the backdrop of the 1940s and 1950s. I mean the description of how eccentric he was at Harvard in 1946 – 50 and his friendship with Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, and his time with The Poet’s Theater in Cambridge afterwards, places him within the context of modern art and literature.

Dery: Yes, those were his Cambridge friendships but as to the work, Gorey must be contextualized in relation to the revolution in paperback publishing from the ’50s to the ’60s, and his place in the revolution of children’s books and American notions of childhood. And then his relationship to the graphic novel avant la letter. He was a ravenous collector of Tintin and a connoisseur of Tenniel and Doré and painters like Francis Bacon and Balthus and Albert York—people you wouldn’t expect. And as you say, that’s the other piece—art history. Where does Gorey fit into art history, especially within the Ultimate Cage Fight between commercial illustration and fine art? We’ve rehabilitated Norman Rockwell as the Vermeer of Shuffleton’s barbershop, so why not Gorey? Why is he not the subject of a one man show at MoMA? The 1990 High and Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture show made the case for George Herriman’s Krazy Kat as proto-postmodern avant-gardism, so why not Gorey? To that end, I talk about the parallels his work has with modern art of the period. If we look at Gorey’s compositions, with their spidery lines, white space, and stippled or crosshatched solids, as abstractions, the work is reminiscent of Franz Kline or Mark Rothko. I even quote one reviewer who said his white-on-white, black-on-black compositions were reminiscent of minimal art.

Rail: It’s fascinating Gorey regarded himself as a writer first. But yet, as a writer, he was so experimental.

Dery: Yes, he does some very radical experiments inspired by the Oulipo writers where he sets himself formal parameters that really restrict his options and then that strategy becomes very generative and inspires extraordinary flights of fancy whether he’s just using a string of words or whether it’s creating apparently causal relationships that evoke if/then logic propositions, but which are closer to surrealist parlor games because they don’t really make sense. He made books that experiment with narrative, like early hypertext—the book of cards The Helpless Doorknob: A Shuffled Story (1989), is a dramatic example.

Rail: It is packaged as a stack of cards in a box. You mention Cortázar’s Hopscotch or Robert Coover’s hyperfictions.

Dery: But he also played with genre. In The Tunnel Calamity (1984) he resurrected a Victorian parlor game known as the peep-show or tunnel book, so-called because one of the most popular applications of this optical novelty depicted the world’s first subaquatic tunnel–the Thames Tunnel completed in 1843. Gorey’s ingenuity is in marrying quirky formats of children’s genres such as the pop-up book and antique novelties like the peep-show book to literary devices scavenged from Dada, surrealism, and Oulipo.

Rail: Your discussion of the philosophical aspects of Gorey’s work is gobsmacking, like when you walk us through the affinities between Derrida and Gorey at the beginning.

Dery: I’m gratified to hear you say that because I was at pains to reassure my editor when the ink was still drying on my contract, “I won’t do in this book what I’ve done so often in the past,” meaning: this wouldn’t be another Escape Velocity, where you can’t swing a cat without hitting a reference to Georges Bataille or Donna Haraway or Lacan or Derrida. That said, there are moments in Gorey where you’ll see little flashes of Derrida because Gorey, too, has a quarrel with language that never ends. He’s fascinated by language but at the same time he’s profoundly distrustful of language, epistemologically. He realizes that you’re always fighting the law of diminishing returns—when you capture things in words, you’re killing off every other possible meaning. His philosophical critique of language is at once Taoist and Derridean. Both critique the hierarchical, binary nature of Western metaphysics—the way the “superior” in such a philosophical dyad exists only in contrast to its “inferior” opposite, or as the Tao Tè Ching puts it, “When people see some things as beautiful, other things become ugly/ When people see some things as good, other things become bad.” Gorey told an interviewer, “I am neither one thing nor the other particularly.” His aesthetic vision, and more profoundly his sense of self, was not either/or but both/and. He’s the master of ambiguity and indirection, puns and pseudonyms. His mission “was to make everyone as uneasy as possible because that is what the world is like,” which is as succinct a definition of the philosopher’s role if there ever was one.

Rail: But there is also your succinct discussion of the philosophical logical fallacy post hoc ergo propter hoc.

Dery: Which is Latin for “after this, because of this” and Gorey’s books really are an object lesson in this logical fallacy. His mastery of the non-sequitur, the way that he phrases things as if there’s a causal relationship when in fact there’s no link between them, reminds us that surrealist free-association and dreamlike juxtaposition are central not only to his work but to his way of looking at the world. When he talks about the Victorian nonsense poem that inspired such moments, he says, “It’s so hard to not make sense in a sensical way.” In The Object-Lesson, for example, when he says, “It was already Thursday/ but his lordship’s artificial limb could not be found,” there’s no relationship between those two things. But that’s the essence of surrealist dream logic going back to Lautréamont’s “chance meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table.” It’s a very difficult thing to pull off, yet Gorey makes it work.

Rail: I love your characterization of him as a Gothic surrealist.

Dery: His first full-fledged venture into surrealism was The Object-Lesson, his fourth book, published in 1958. Edmund Wilson wrote about Gorey’s surrealism in his New Yorker essay, saying it reminded him of Max Ernst’s collage novel La Femme 100 Têtes (1929), which Gorey loved, along with Une semaine de bonté (1934). But The Object-Lesson also contains perhaps the single most beautiful line of Gothic-surrealist poetry Gorey wrote: “On the shore a bat, or possibly an umbrella, disengaged itself from the shrubbery, causing those nearby to recollect the miseries of childhood.”

Rail: That passage where you talk about that line is marked in my book with “MD,” i.e., moments of magisterial Mark Deryisms. Let me read the quote: “His linkage of the twilight flight of a bat, or a forlorn umbrella, with recollections of childhood crosses Proustian reverie with gothic (the bat) and surrealist (Magritte’s umbrella) symbolism. The confusion between bat and umbrella recalls surrealism’s combination of incongruous elements (quintessentially, ‘the chance meeting, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella’ in Lautréamont’s novel, Les Chants de Maldaror) to create a new, dreamlike synthesis that destabilizes everyday reality, if only for the moment. The irresolvability of whether the dark, flapping thing in The Object Lesson is bat or umbrella has the effect of making us view it as an uncanny conjunction of both.” You are so precise. Not a moment of flab in that analysis!

Dery: But that’s Gorey too—you see, Gorey’s books, despite their bagatelle-like length are, as we’ve touched upon, profound. He described them as “Victorian novels all scrunched up.” The Object-Lesson is itself only thirty pages. Its text is only 224 words long, yet it feels like a philosophical novel in miniature—almost Beckettian, in spots. (Contrariwise, some of Beckett’s best texts remind me of Gorey in their haiku-like compression—the incredibly spare passages in his plays, the monologues that are exquisitely distilled.) Ironically, Gorey’s “silent” (meaning: wordless) book The West Wing (1963) is his incomparable masterpiece. Nowhere is his synthesis of surrealism and the gothic more seamless. I would also include The Willowdale Handcar (1962) and The Iron Tonic (1969), in which text and image are like Giacometti stick figures, whittled down to their essence. I quote Ronald Firbank, Gorey’s great influence during his Harvard years, who said, “I think nothing of filing fifty pages down to make a brief, crisp paragraph, or even a row of dots.” That’s Gorey all over. He’s the master of the ellipsis. This is what he got from Firbank and Balanchine and surrealists such as Magritte: the conceptual lacunae, the reverberating silences, the white spaces on the page, the things left out.

Rail: Which is also why your comment, and I totally agree, that the Amphigorey anthologies produced in the ’70s, actually undo the absurdist, philosophical aspect of his books.

Dery: Yes, his individual books are structured by a brilliant sense of visual and narrative rhythm, so the Amphigorey anthologies, while they exposed him to a mass audience, are a deal with the devil. They do formal damage to his books as gestalts. For example, in The Unstrung Harp: Or Mr. Earbrass Writes A Novel (1953), Gorey plays a kind of conceptual counterpoint between the text and the image, where you have nothing but a few lines of text on one page and then the illustration on the facing page. He was influenced by silent film and ballet and the book takes on the quality of a time-based medium; Gorey is doing something very interesting with time in his presentation of the succession of information. We look at a page and read an isolated sentence or paragraph, soaking that up, and then we have to turn and look at the image without the text. There’s a dialogic relationship between them. Again, it’s the Magritte in Gorey, but also the Barthesian, who understands that a work of art is best when it’s completed by the reader. But it’s also his interest in Asian philosophy and aesthetics talking, the Gorey of The Tale of Genji and Taoism and Zen Buddhism. For example, in Japanese court music, gagaku, which is ancient court music, there are these enormous spaces—you will hear a pair of claves rattling to a stop and then a single string twangs and then there’s thirty seconds of pin-drop silence, nothing but the rustling of the musicians’ kimonos, then someone strikes a gong, which has the effect of an exclamation point.

Rail: Or his obsession with Balanchine.

Dery: His interest in ballet was also because ballet is untranslatable into language. It is irreducibly about itself. Balanchine was also a draftsman but his drawings were sketched in space with bodies. The sharp attack he demanded in his dancer’s footwork is like the machinelike precision of Gorey’s crosshatching and stippling. And Balanchine’s ballerinas, with impossibly long legs, are the choreographic equivalent of Gorey’s line, though Balanchine is drawing on thin air.

Rail: Gorgeous!

Dery: Gorey responded to Balanchine’s highly stylized mastery of form—the geometer’s love of bodies resolving in kaleidoscopic patterns, then reassembling into new ones. It’s not much of a stretch to see the visual aspect of Gorey’s work as an extended meditation on pattern.

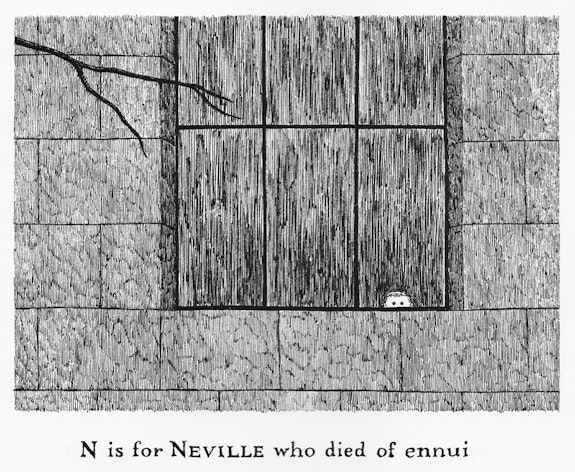

Rail: As you call them, “eye-buzzing exercises of pattern-on-pattern” which are everywhere. I especially love the drawing in The Gashleycrumb Tinies (1963): “N is for Neville who died of Ennui”—it’s both busy and utterly spare.

Dery: Which also relates to the Paul Éluard quote, “There is another world, but it is in this one,” and the quote from the Oulipo writer George Perec where he says, “Things aren’t as they appear, but they aren’t anything else either.” Now, those two quotes were among Gorey’s two favorites and they are depthlessly deep, and—at the risk of insufferably pretentiousness—they remind me both of Object Oriented Ontology and Heidegger in the sense of the uncanniness of the everyday. “Things aren’t what they appear, but they aren’t anything else either” strikes the amateur Heideggerian in me—I emphasize “amateur”—as relating to a book I’m reading about Heidegger and the uncanny by Katherine Withy called Heidegger: On Being Uncanny (2015). She talks about how Heidegger’s ideas appropriate Freud’s uncanny in such a way that there are three things you can imagine about the uncanny. One, it’s a property that inheres in things. In other words, things are inherently uncanny. Or two, the uncanny isn’t instantiated in something but is an experience humans can have, that deeply disquieting emotion we call the uncanny. Or, finally, the very nature of existing—the “is” of “is”-ing—can itself be uncanny. In other words, being itself becomes, in the moment we confront it consciously, inescapably uncanny. Withy is interested in the third route: when we start to think about being and we conduct phenomenological probes into the nature of being using the tools Heidegger has given us, everything becomes uncanny. In a word, it weirds you out and, if you’re like most of us, you pull back from the abyss. Gorey got a glimpse of that, I think, which is why the Éluard and Perec quotes made sympathetic vibrations in his mind.

Rail: Connect this to Gorey.

Dery: For instance, in The Other Statue (1968), one of his little rhyming couplets is about a gust of wind that comes up out of nowhere and rustles the trees. Gorey has drawn these trees so beautifully and with such pointillistic stippling that you can almost see the leaves moving. The harder we stare at his eerily beautiful drawing of a grove of trees at dusk, the more their leaves seem to rustle on the page, animated by countless tiny pen strokes. And then you realize, when trees sway together and all the leaves move in concert, it’s like the entire stand of trees becomes a complex organism. Is that a form of animism? Is it like a Japanese ghost story in which inanimate objects have an inner life, and the ghost isn’t the shade of a departed ancestor but is an indwelling presence in a given location? Or is it closer to that Heideggerian or OOO (Object Oriented Ontology) sense that objects are uncanny because in the deepest phenomenological sense we don’t really know what they are? We’ve all had that moment, especially on a Santa Ana afternoon, when it’s deathly still and infernally hot and there’s nobody around—I’m thinking of a desert state like California, where I grew up—and a breeze sighs through the eucalyptus trees, rattling the loose bark and tossing the tops like hairy heads . . . it can be very uncanny, very disquieting.

Rail: Wow, that’s beautiful.

Dery: I’ve never gotten over the realization that the self is only visible when it’s cloaked in language. It’s the insight that has driven my life. I sort of write myself into existence. In Withy’s book about Heidegger and the uncanny, she quotes from a collection of oral histories of people with anxiety disorders describing depersonalization and it’s very similar to the philosophical vertigo that happens when you drill deep into the Heideggerian uncanny as she envisions it. The world becomes instantly defamiliarized; the self becomes alien.

Rail: That line by Jane MacDonald at the end: “He wanted the interior that was never spoken.” Or, as you say, unlike the Freudian repressed, everything in Gorey stays repressed. Which might be the moment to discuss Born to Be Posthumous as a masterful example of mainstream queer scholarship. People like Gorey are the reason the word queer exists!

Dery: What I’m talking about is the difference between identity then and now. One of his dearest friends at Harvard, Lawrence Osgood, as well Andreas Brown of the Gotham Book Mart, both of them contend that whatever put him off sex for life happened in high school. The story that’s most reliable, that’s told by people who really knew him intimately is, “I tried it once. I didn’t like it.” Of course, Gorey’s sexuality is a fascinating peach pit at the center of who he is but I didn’t want to be reductionist. I didn’t want this to be queer studies for dummies.

Rail: And yet, you also discuss Gorey’s collaboration with George Selden, also a prolific children’s book author (The Cricket in Times Square [1960]) whose pornographic book, The Story of Harold published under the pseudonym Terry Andrews . . .

Dery: . . . Edmund White described as the earliest document that renders the feel of Downtown Village gay life in the 1970s. White describe it as “the mix of high culture and perverse sex, the sudden transformation, from a night at the opera to an early morning at the baths,” shot through with “the Sade-like conviction that sexual urges are to be elaborated rather than psychoanalyzed . . .” So, while never identifying as gay, Gorey happily illustrated Selden’s very gay book, fisting scenes and all. I mean, he clearly had no problem being identified with the book, although when I said to the feminist writer M.G. Lord, there isn’t anything pornographic about the illustrations Gorey drew, she said, “No, look, again. If you look at the wallpaper with a looking glass, the pattern is made up of all these little penises.” And she was right! He also published a couple of gay-themed single-panel cartoons in the National Lampoon in 1973.

Rail: But Gorey’s queerness can also be connected to his deep love of nonhuman objects, animals, stones, and of course, “Cats, like books, were always there for Gorey.”

Dery: You must have loved the one book review he did, of Animal Gardens by Emily Hahn, a book which for Gorey proved zoos are a cruel kindness. It’s another way in which he was ahead of his time. The animal-rights movement came into being in 1975 with Peter Singer’s A New Ethics for Our Treatment for Animals. Well in advance of that, Gorey revealed his deep sympathy with nonhuman beings. I quote him, “Few people seem to notice that a largish part of my stuff is not about human beings. I mean I’ve done several books about inanimate objects…I just don’t think humanity is the ultimate end.” This is the man who insisted on saving earwigs when family members discovered them on flowers and who didn’t like putting out poison bait for ants. When he died, his largest bequest was to nonhuman beings. He mandated the creation of the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust whose purpose was to use any income generated by his work in the service of animals.

Rail: Gorey—so many avants. Is this really the theme of the book?

Dery: But, remember he was the Benjamin Button of avant gardism, evolving backwards from the Firbankian aestheticism of his Harvard years to the Edwardian surrealism of New York, creating self-deconstructing book designs in 1989 such as The Raging Tide, The Helpless Doorknob: A Shuffled Story, and The Dripping Faucet, whose interactive nature ensured a new narrative twist with every reading. And by the time he’s a white-haired man, living in his home on the Cape in an installation-for-one of hand-made stuffed animals and objets trouvés, he’s a kind of gleeful Dadaist. He did such things as arrange a flock of pewter salt and pepper shakers on a tray, balanced on stool so they looked like people, or a chess game. He collected all kinds of spherical objects—bocce balls and glass fishing floats which he put in a back room, and called it The Ball Room. Eventually, there was just enough space in the center of the room for an exercise bicycle, prescribed by his doctor, and so in his late years, surrounded by his spherical objects, he pedaled and read.

Rail: I love that image of him.

Dery: But when all is said and done, the aspect of Gorey I was proud of excavating is how the whole David Lynchian gothic-bodies-buried-underneath-the-perfectly-manicured-lawns trope of Blue Velvet that fuels contemporary pop culture like the TV series Riverdale—a dark version of the Archie, Betty, and Veronica universe—all of this begins with Gorey. It’s ultimately what makes Gorey so relevant to the present, offering, in a kind of timeless way, a code signaling a conscientious objection to the present.

.jpg?w=575&q=80&fit=max)

.jpg?w=575&q=80&fit=max)