One evening toward the end of February, my phone rings and the name “Vincent Livelli” pops up on my screen. In the last year or two, a stab of fear has shot through me whenever I see Vincent’s name that it might be a neighbor calling to say he’s died.

“Okay, Bliss, it’s Vince,” he says impatiently, like he’s got a busy afternoon ahead of him. “I have some information for you. You need to order face masks for you and the children because of the co-rona-virus.” He pronounces the disease slowly in his earthy Brooklyn drawl in case I haven’t heard of it.

“Vincent! Hi!” I shout into the phone. He’s 99 and almost entirely deaf.

“That’s all. I’ll hang up now. I love you. Bye-bye.”

My husband comes into the kitchen. “How’s Vincent?” he asks.

“He says we should buy masks.” I raise my eyebrows. Over the years, Vincent has shared many of his theories: American children could get lead poisoning from toys made in China; piping small amounts of nitrous oxide into the atmosphere would cure drug addiction; sound waves will outlast everything else, sending echoes of his precious musica into eternity. The lead in the toys checked out, but my husband agrees that the chances we’ll be needing masks anytime soon are slim.

Vincent was one of my father’s best friends since they met in the cafeteria at Brooklyn College in 1938. My father, Anatole Broyard, was a light-skinned black kid from Bed-Stuy, which made him stand out among a student body full of Jewish refugees, even if many of the students weren’t aware of his racial identity. Vincent, an Italian from Fort Hamilton, was a misfit too, suffering from hearing loss since early childhood from eating lead paint. Tall from a young age, he was seated through grade school in the back of the classroom, where he couldn’t hear the teacher. Catching him staring at clouds out the window, one hit him on the head, pronouncing him “dead from the neck up,” which convinced him and everyone else he wouldn’t amount to much.

Nevertheless, Vincent managed to attend Brooklyn College, where he and my father forged a friendship through a mutual love of Cuban music. They would get off the subway in Downtown Brooklyn to stop in at one of the few shops that carried Latin albums. They squeezed into the listening booth to puzzle out lyrics full of puns and sexual innuendos. My father started tagging along to the Afro-Cuban dance halls in Spanish Harlem where Vincent had become a regular. Their friendship survived World War II, when my father was an officer in a stevedore battalion and Vincent served in the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor to the CIA) and as a secretary to General MacArthur. They wrote letters from their respective posts. When Vincent’s father later found them, infused with the urgency of young men in war and full of talk about women, sex, and romantic poetry, he burned them, fearing his son might be gay.

After the war, they rented an apartment together in Greenwich Village. My father, who eventually became the chief book critic for the New York Times, wrote in his Greenwich Village memoir about bringing the Village intellectuals he’d gotten to know — Dwight Macdonald, Clement Greenberg, and Delmore Schwartz — to the Park Plaza, their favorite dance hall in Spanish Harlem, which Vincent had introduced him to. The trip, a sort of safari for “authenticity,” became weekly. At college, my father had begun experimenting with letting people think he was white, and these sojourns became a way for him to stay connected to the aspects of blackness that he loved without having to actually be seen as black himself and suffer the indignities and hardships experienced by most African-Americans in the 1930s and ’40s. That my father’s familiarity with and chronicling of a black and brown Harlem scene helped to cement his reputation among the mostly Jewish cultural gatekeepers was ironic to say the least, and he had Vincent to thank for it.

Vincent and I became friends in our own right after my father passed away in 1990. I first met him when he showed up at the burial of my dad’s ashes on Martha’s Vineyard. It was an intimate affair with no other guests from off-island. A local minister friend led a simple service, then my mother placed the urn in the hole that had been dug at the grave site. Just as we were about to pass around a shovel to fill it, Vincent shot through the crowd and threw himself on the ground, lifted the urn from the grave, and kissed it.

Vincent’s apartment in Greenwich Village, which he’s kept since the 1960s, is a fourth-floor walk-up with narrow hallways and a steep metal staircase that winds up the back. When I started visiting him, the walls were dinged and the linoleum was peeling, but as the older generation of rent-controlled tenants died out, the hallways got nicer. Entering his place is like passing through a warp of time and space. The walls are covered with striped fabrics and Arabic tapestries; the furniture would suit a Turkish teahouse. Intricately carved wooden shutters block the windows, and a dim starry light emanates from the metal cutouts of Moroccan lamps. When he still traveled a lot, he would lend out his place to foreigners he met overseas. They always had trouble locating the lights. I liked to imagine their reaction when they finally got the place lit and found themselves inside One Thousand and One Nights.

Vincent attributes his longevity to climbing up and down the four flights of stairs. Besides being hard of hearing and having a hernia that forces him to limit his diet, he’s in very good health. In the early years of our friendship, when Vincent was in his 70s, he would fly up the stairs, leaving me panting behind him. One of the stories he likes to tell about the Greenwich Village years concerns a party he and my dad attended in 1946 to celebrate the publication of Anaïs Nin’s Ladders to Fire. My dad told him that Nin gauged the virility of her potential suitors according to how quickly they could make it up the five flights to her apartment. Vincent apparently impressed her, because he went back for a rendezvous a few days later. She wrote about the evening’s guests in her diary: “Anatole Broyard, New Orleans–French, handsome, sensual, ironic; Vincent, tall and dark like a Spaniard.” Vincent brought some Afro-Cuban records. “He quietly placed one on the phonograph and opened his arms. He is a professional dancer, smooth and supple.”

As a broke young writer living in Brooklyn in the 1990s, I’d bring a girlfriend or my current boyfriend over to Vincent’s place in a pilgrimage to Greenwich Village bohemia and the life that my father left behind — after he married my mother, in the 1960s, they moved out to a Connecticut suburb, where they raised me and my older brother. On those visits, we’d drink rum and get high, which Vincent called “turning on” — the first person he turned on with was Charlie Parker — and flip through his many scrapbooks. There were photos and clippings of all the Village nobility who’d graced their booth at the San Remo, the bar where they’d spent many of their Greenwich Village nights after the war. Run by some tough Italians named the Santini brothers, it was a place where you might find Dylan Thomas, James Baldwin, Jackson Pollock, or W. H. Auden. It had been my father’s dream while stationed in Yokohama toward the end of the war to open a used bookstore in Greenwich Village. Vincent helped him clear out an old plumbing-supply shop on Cornelia Street and set it up. After closing time, they sat around the potbelly stove in the back room talking about books and women, polishing lines to use back at the San Remo. Soon the Santinis were saving a booth for them and their circle: the experimental filmmaker Maya Deren; the author William Gaddis, in whose novel The Recognitions both my father and Vincent make cameo appearances; and Beauford Delaney, one of the few African-American painters among the Abstract Expressionist crowd.

Several scrapbooks were filled with postcards of all the ships he’d worked on, and he had stationery from hotels in Sidi Bou Said in Tunisia, Bagan in Burma, and Finisterre, Spain, which the Romans mistook for the end of the world. In 1948, Vincent was hired as the assistant cruise director on the SS Uruguay for its maiden voyage to Buenos Aires, and he would spend the next 25 years working on cruise ships. He made over 60 transatlantic journeys. In one of the many letters he’s written to me, Vincent explained his decision to leave on that first cruise: “In 1946–7, conversations at the San Remo, that gathering place of existentialist thinkers, were becoming more and more rarefied. I found himself falling behind as though unprepared for an exam. I sought to excuse myself with my reputation still intact, to exit with dignity. Imagine escaping from the Village where everyone went to escape … Was escaping itself a way of being ‘original’?”

Back then, most cruise lines didn’t offer much in the way of entertainment. Vincent became a pioneer of the schedule of daily activities, including costume contests, pool games, brisk walks around the promenade, and dance performances. He once staged a mock prizefight between two grandmothers in which one woman, using a well-placed toupee, pretended to tear out the other’s hair. He credits his success to his ability to remember names and a facility with languages. Despite his hearing loss, he spoke six: English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, and a bit of German. He later moved on to tour buses and spent the 1970s and ’80s working for the Gray Line Bus Company. He told them they could save money (and he could earn more) by putting a mix of nationalities on his bus, and he’d give the tour in multiple languages.

His albums also had photos of Afro-Cuban stars and playbills of their performances. Before the war, Vincent had temporarily withdrawn from Brooklyn College and started performing as a dancer in nightclubs in Manhattan, Detroit, Chicago, Miami, and even Havana. He met the musicians who would become the stars of Latin music when many of them were just starting out. It was impossible for my friends and me not to feel that our own lives were boring by comparison and make all sorts of promises on the subway ride back home to seek out more adventure.

Vincent would tell stories about his life and read snippets of the essays he was always writing. How his Genovese grandfather was kidnapped by gypsies as a teenager and forced to play the hurdy-gurdy in a circus that traveled through the German forest until he escaped in St. Petersburg and sailed to New York in 1861, where he settled among the Italians in Greenwich Village. His grandfather shot up the ranks of a piano-strings factory, allowing him to purchase a tenement building on Sullivan Street.

Vincent grew up in his grandfather’s building. One of his earliest memories was being quarantined after his father had influenza and the doctor worried he might have been exposed. This was during one of the flare-ups that occurred in the years after the 1918 outbreak, when health officials feared another epidemic.

Always, Vincent had been lonely because his parents wouldn’t let him play with the other Southern Italian kids who lived nearby. They were deemed too rough, despite his own mother being Sicilian. Anyway, those kids resented his family for being the landlords. Vincent turned to a shortwave radio for companionship. The Hawaiian music he managed to tune in was too soft and mellifluous to penetrate his hearing loss, but the Cuban music coming from live orchestras at the Hotel Nacional in Havana was a different story, as he recounts in his essays:

“Siboney,” the theme song of the Lecuona Cuban Boys, came in, full of static, fading in and out, at times completely silent, clearer in summer than winter and very late at night. “Turn off that radio!” my dad would shout from the other room. Turning down the volume a wee bit, I would bring the radio under the sheets with me, married as it were, to the music.

In another essay, he describes how “the drum began to be something I needed biologically, it seemed. It filled the empty quality of deafness the way the gigantic Wurlitzer organ at the Paramount Theatre filled the house. To the rafters.”

In 1941, when he was performing in Miami, he met a benefactress who offered to pay for a semester at the University of Miami, which had an exchange program with a university in Havana. Once there, he took a boat across the Havana Harbor to the district of Regla, where he sought out a Santero priest to teach him about Babalu-ayé, the Orisha spirit whom Miguelito Valdés invoked in his signature song, which was later made famous by Desi Arnaz in I Love Lucy. For the initiation ceremony — in which Vincent’s old spiritual self would die and he would be inhabited by a new consciousness and destiny — the Santero hit Vincent over the head to “seat” his new Orisha in his crown and declared that he was destined to carry la musica around the world. It was a charge he took seriously, pressing upon anyone who would accept them homemade cassette tapes of his Afro-Cuban heroes. (I have a shoe box full of them in my basement.) He even left them in hotel rooms “like the Gideon Society leaves the New Testament.”

We would go dancing at S.O.B.’s down the street, if we were splurging, or at community centers in the Bronx, if we were tight. Vincent tried with little success to teach me to salsa. My dancing had too much disco in it, he complained. In a letter, he wrote that I shouldn’t feel too bad. My father hadn’t been a great salsa dancer either. “To be excellent at dancing, it is essential to be a bit out of control — overwhelmed. The true finale of a dance should be a collapse … a surrender to the rhythm and acknowledgment of the ‘spirit’ in the dance, a bowing down before it that brings you to your knees.”

In many of his letters and essays, he wrote about sex, how consumed he and my father were by it. He described in long detail how useful the columns at the Park Plaza were for holding up a woman as you grinded against her, gyrating toward orgasm. He’d been thrown out of the Waldorf-Astoria for dancing in this true Afro-Cuban rumba fashion, not the sanitized Arthur Murray version. He described how the Park Plaza was able to charge ten cents more for admission after installing a large fan that sat at the top of the stairs to the basement, where the bathrooms were located. “Currents of air carrying male and female pheromones floated over the dance area. In this way, ethereal substances, sex steroids, were blended into the suggestive lyrics, the flirtations in progress, the orchestral vibrations, the sweet-smelling tobacco, libido Latino, overlapping perfumes floating in the congested intimacy … filled to the brim with sensuality.” Getting older seems not to have had a dampening effect on his interest in the subject. In the last couple of years, he reconnected with an old girlfriend in Florida. They speak every night. Vincent told me he’s worried that one of his aides will read the transcript on his CapTel phone for the hearing impaired and be scandalized.

A rotating cast of friends appeared at his frequent parties, people who worked in bookstores and auction houses, filmmakers, writers, artists, musicians. Not long ago, the model Alexa Chung showed up. I never met any family members until recently. I knew he had a son in Virginia who had addiction issues and would sometimes call to ask for money. (I learned later that he’d been a medic in Vietnam and suffered from PTSD.) Vincent rarely spoke about him except to say they were estranged and that he’d done his best to be a good father. I never saw Vincent with a girlfriend, although he talked about the important women in his life: His first love, Rita, whom he met at a nightclub in Manhattan. She was a model and dressed like a million dollars. When he came into the San Remo with her on his arm, the Santini brothers called out to him “Valentino!” They made love on the top of a double-decker bus late at night, in Central Park, and on the roof of her building.

Then there was his companion of later years, Eunice. He met her during a cruise; she had an arrangement with her husband under which each of them could take vacations with their respective lovers. She liked to wear very high heels, and Vincent gently held her arm as she navigated the cobblestones of European cities. Not long before I came on the scene, he and Eunice had met up in Paris, where she’d paid for him to get a face-lift while she got her eyes done. After the procedures, they recovered holding hands in neighboring hospital beds.

The most recent time I accompanied Vincent up the stairs was a year ago, after his 99th-birthday party, held at Johnny Cruz’s Salsa Gallery, a small museum and community space on 107th Street. On the Uber ride back downtown, Vincent reviewed the speech he’d made to the 30 or so attendees. Many were musicians and aficionados of Latin music. Vincent was a revered figure among them because he’d seen Machito, credited as an originator of salsa, play at New York’s Half-Moon club in 1938 and Miguelito Valdés perform in 1941 at the Beachcomber in Miami. Vincent had been taught to dance by Estela of the Afro-Cuban dance troupe René and Estela, who performed their famous corkscrew rumba in Another Thin Man (1939). And he saw Chano Pozo beat his conga in the 1940 Havana Carnival before Pozo became Dizzy Gillespie’s first Latin percussionist. Vincent had carefully name-checked each of them as he talked. There were all dead now, he said in the car. “But by saying their names, I hope they will hear me.”

When we pulled up to his building, Vincent insisted he could see himself inside. I reminded him of the big bag of presents. Up he went, me one step behind, carefully navigating the narrow triangular treads where the stairs turned, hand over hand up the inside rail like climbing a rope. Only at the top did he rest, gripping the railings tightly as he panted over the stairwell while I hurriedly opened his door.

Another, bigger party was in the works for Vincent’s 100th birthday in April. It was to be down the street in the gallery of a local church; at least 50 people on the guest list to whom he could give his speech. For months, he’d been talking about how determined he was to make it to 100. Those of us in his life seemed to need this milestone as much as he did. And yet, the last time I visited Vincent, this past December, he spoke to me for the first time about what he wanted when he died. He has already made arrangements with a funeral parlor to be cremated and for his ashes to be spread over the ocean during a monthly boat ride chartered by the funeral director. But he’d recently been thinking that some of his ashes could be commingled with the leftover portion of my father’s that hadn’t fit in the urn and were now sealed in a vase on my mother’s bookshelf. My slight hesitation made him try to take it back, suggesting that perhaps my mother would be jealous. I did wonder.

There is a term for elder adults who have no family or close friends to make care decisions on their behalf: “the unbefriended.” As the COVID crisis began to hit the city, Paula Kieffer, who is 50 and lives on the first floor of Vincent’s building, started to check more frequently on her upstairs neighbor. For years, she had witnessed him holding court on the stoop. He wore his guayabera or a replica of his cruise director’s uniform with nautical patches on the shoulders that he’d sewn on himself. Carrie Bradshaw’s house on the next block brought a constant parade of tourists. If Vincent caught sound of another language, he would jump in and ask where they were from. More often than not, he’d been to their home country. People were charmed. Except for his health aides, who always seemed to be changing, and the occasional visitor, this was his life as far as Paula could see it.

She brought up bottles of hand soap, Clorox wipes, and paper towels for him to use and, more importantly, for his aides coming in from the outside. He depended on them to heat his meals-on-wheels and steady him as he moved around the apartment, since he refused to use a walker or cane. So Paula became alarmed in mid-March when she started running into the aides on their way out not long after they’d arrived. Vincent had dismissed them when he learned they took the subway to reach him. One, who had the week before borrowed Paula’s vacuum and filled up an entire bag when cleaning his apartment, Vincent sent away when he discovered her husband drove a taxi. A week later, she found his door open and clothes strewn on the floor, tripping hazards. The place smelled like a latrine, and the few dishes he had were piled in the sink. She considered calling Adult Protective Services. Paula had worked for many years at Mount Sinai connecting hospital patients to public services and understood what that would mean: A guardian, a stranger, would be appointed to manage his care and finances, and she knew Vincent well enough to appreciate how much he valued his independence.

I’d met Paula briefly eight years earlier, after Hurricane Sandy had knocked the power out across Greenwich Village. When I couldn’t reach Vincent on the phone, I’d driven to his apartment and climbed up the dark stairwell by the dim light of my cell phone’s face (this was before they came with built-in flashlights). I could hear him moving around inside, but the door was locked. Despite pounding and yelling his name, he didn’t hear me. My racket drew Paula and her husband, Gil, out of their apartment. They promised to let him know I would come get him as soon as they saw him. When I drove back to pick him up two days later, I was alarmed to find myself in the position of coming to his rescue. Wasn’t there someone who lived closer or was an actual relative watching out for him?

A few weeks after Hurricane Sandy, I was back at Vincent’s. He had turned on his kitchen sink and forgotten about it, flooding the apartments below him. Paula and another neighbor banged on the door, but he couldn’t hear them. I got a call wondering if I had a key. I didn’t. Paula finally crawled out on the fire escape from another neighbor’s window and climbed down to his floor. His window was open. She brushed aside the sculptures and vases lining the sill to wiggle inside. There he was in the living room lounging in his bathrobe, watching the Jets on closed caption, his hearing aids on the table beside him. When Vincent discovered what had happened, he was very upset and worried that his landlady might use the incident to force him out. It wasn’t the first time he’d caused a flood.

And then, eight years earlier, when Vincent was 84, there’d been the fire. He woke up to find the curtains surrounding his bed ablaze. He escaped unscathed except for singeing his eyebrows, but much of the apartment and his possessions were burned. He showed up at the community center on Lex and 105th for Julia’s Jams, a weekly gathering for Afro-Caribbean music and poetry, looking disheveled and smelling of smoke. Aurora Flores, a Puerto Rican writer and musician who put on the event, asked if everything was okay. He shared what happened, sounding sheepish. The landlady, who blamed him for his habit of draping scarves over his lamps, was trying to get him out and refused to repair the damage. He eventually moved in with a cousin in Pittsburgh, but he wrote Aurora long letters about how much he missed New York City, especially the Village. She eventually found him a room uptown at a friend’s and a lawyer to represent him pro bono. The lawyer located the fire report, which stated the cause as faulty wiring, and pursued legal action until the landlady finally did the bare-minimum renovation so he could move back in. I was living in France at the time and only found out about the whole episode later.

The flood was the first time I heard Vincent talk about leaving his apartment. He acknowledged that he might have to someday, but he wanted it to be on his own terms and not because someone forced him out. He came up with the simple solution of replacing his sink trap with a mesh one so there was no danger of its becoming accidentally stopped and overflowing.

With two small children and a full life in Brooklyn, I made it to the city less and less to see Vincent. But I’d get a letter from him or we’d talk on the phone. New friends kept coming into his life, which reassured me. There was a photographer named Tina Buckman whom he met on his stoop; an MTV exec named Matteo Parillo, who lived upstairs; and a musician in his mid-20s named Lewis Lazar, who approached Vincent after overhearing him at a local café talking about Cuba.

Lewis began collecting Vincent’s writing into a volume, which a friend with a small press had agreed to typeset and put up on Amazon, where it could be printed on demand. Vincent’s 96th birthday was approaching. I got an invitation for a party at his place that would coincide with the debut of the book. Lewis recently told me that task felt enormous — the piles of paper kept growing like a “molten volcano of literature.” One day, while Lewis was there sorting, Vincent mentioned that he’d picked up some pills from a doctor in Chinatown. He had decided that he was going to check himself out on his birthday. He’d had a good life and the hernia was getting to him. It was time to go. But he was really hoping to see the book beforehand. Lewis had a month to get it done. Lewis showed up late to the party, bleary-eyed and wild-haired, with the proof of the book, titled Historietas. He promised it would be available for purchase in another few days. “After I gave it to him,” Lewis told me, laughing, “he seemed to forget all about his plan.”

Lewis didn’t tell me this story until recently, but I recall raising with him at the party the question of how Vincent wanted to play out the rest of his life, as I would from time to time with his other friends. Had he said anything to Lewis? What would happen when he could no longer make it up the stairs? Anytime I brought up the subject myself, Vincent would get annoyed and tell me not to worry. I also knew that Vincent didn’t have any savings left, so I wasn’t sure what his options were. He’d already sold off most anything of value he’d had: his collection of Latin dance-hall posters, the objects he’d collected during his travels. After he paid his rent, utilities, and his portion of his aide service, there wasn’t anything from his Social Security check left over. He depended on SNAP and the nonprofit God’s Love We Deliver for his food, and on his cousins covering him whenever he was short. Lewis seemed put off by my question, saying something to the effect that Vincent wouldn’t want us to dwell on such topics at his party.

Around this time, a young woman named Annie Basulto entered Vincent’s life. She sought him out as part of a documentary she was making about her great-uncle who was a noted Cuban bandleader in the 1940s. Annie took up where Lewis left off, launching the Vincent Livelli Preservation Project. She arranged for him to give a talk at the local library branch and organized teams of volunteers to transcribe his writings to create an archive. Vincent recently told me, “I was prepared to sit in front of a television set and just keep quiet and die. And then came along Annie.”

Early on, she got involved in his care. When his hearing aids broke or he clashed with his home health aides, Annie would sort it out. She became the person that Vincent or his aide would call when he had an emergency. She does it willingly, she told me, for the man she refers to as her best friend, because no matter how dire the circumstances, he always makes her laugh. Once, when riding with him in the back of an ambulance from one emergency room to another, Vincent asked the driver to dim the lights to make it more romantic.

Over time, the calls came more frequently, and it was getting overwhelming, maybe even for Annie. Shortly after Vincent’s 98th birthday, his cousin John helped him secure a spot at an assisted-living residence that accepted Medicaid. It was up in Spanish Harlem, with a corner room on the seventh floor overlooking Central Park. But the day before he was to move, he announced that he’d changed his mind. He explained his reasoning in a dictated email to his friends: “With a large staff as a cruise director for many years, the job entailed morale and good cheer. At Lott Facility I am unable to fulfill that goal … There are 125 very depressed people at Lott’s. In the Village there is inspiring vitality, fashionably dressed actors, models and supporting neighbors … My park is Washington Square Park not Central Park.”

His friends had fallen into two camps. There were those, me included, who thought it was better to secure a spot in a nice place now rather than waiting for the time when he’d not be able to get himself back up the stairs. And then there were those, who apparently held more sway, who thought that leaving his apartment would kill him. They were right. Had the move been successful, Vincent would most certainly be at much greater risk of exposure to COVID, and he’d be forced into even greater isolation than he is now.

While none of us has any actual authority over Vincent, there’s been an ongoing group chat among six or seven friends — Team Vincent, we call ourselves — since the assisted-living debacle. When the virus forced the cancellation of his 100th-birthday party, we began to brainstorm alternative ways to celebrate and, most of all, to figure out how to keep him safe and socially engaged during these months of quarantine. The few who live close by have been visiting, although less frequently, wearing masks and keeping their distance. Despite recognizing his increased vulnerability because of his age, he strikes an optimistic note when he hears my concern on the phone. “I just have a feeling that I will survive as I have been surviving all my life with very close encounters in all kinds of situations.” Other than one trip to the bank in early March, he hasn’t left his apartment or even ventured downstairs to sit on the stoop on warm afternoons. He is keeping busy on some new writing — about cultural responses to social distancing — and fielding interview requests, one from a blog in France dedicated to Beauford Delaney’s memory, another from a Cuban writer whose latest project features Vincent as its main character. Those of us who love him are determined to make sure that he didn’t survive for a hundred years only to be felled through accidental exposure to a virus.

After sharing her concerns with someone in the group, Paula has joined the chat and keeps everyone updated on the aides’ comings and goings; whether they agreed to wear the masks, gloves, and shoe covers; the disconcertingly slow pace with which the hand soap, cleaning spray, and paper towels are being consumed; the questions of what he is eating and how he is heating it when the aides aren’t there and whether he has remembered to turn off his hot plate; if he should or shouldn’t leave the door open at all hours, so if he falls, someone will hear him; and wouldn’t a Life Alert solve that problem?

Vincent continues to send his aides home after politely inquiring if they required public transportation to get to him. Efforts to locate someone within walking distance of Greenwich Village have so far been unsuccessful. Annie keeps calling the agency to get them to send a new aide with the hope that Vincent will realize that the important service they provide (at risk to themselves too) outweighs the extra exposure to the outside world they bring.

He seems to sense when his friends have been talking among themselves or to his aides about his care. “I have to know what’s going on, what people are talking about,” he says, sounding frustrated during a recent call. “I feel at a hundred that people don’t believe what I say, but I think very clearly.” He interrupts himself to ask the aide that day, Fatima from Senegal, “S’il vous plaît apportez moi de l’eau?” (“Will you please bring me some water?”) “I love being able to use my language,” he tells me.

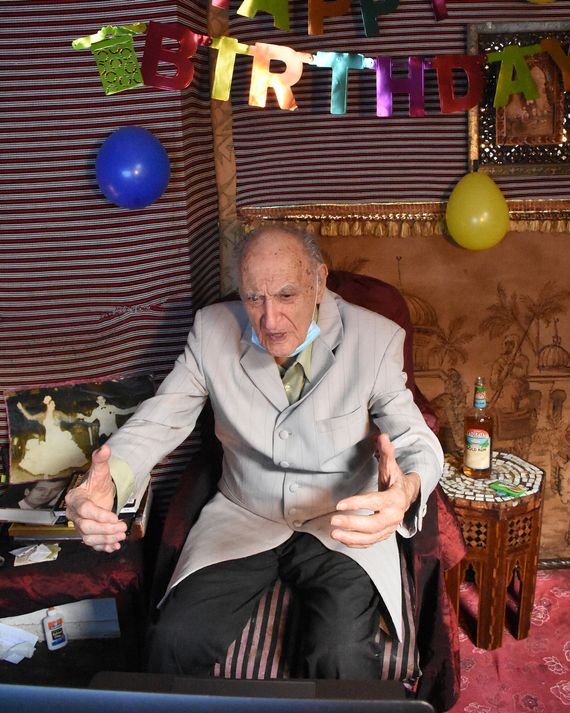

On the day of his birthday, Matteo from upstairs puts on an N95 mask and comes in while Vincent is taking his afternoon nap. He hangs balloons and a birthday banner behind Vincent’s favorite chair and props up his computer on a table. God’s Love We Deliver dropped off a cake with candles that spelled out 100 on top. Paula has made him a special dinner: chicken, Brussels sprouts, and mashed potatoes. At 5 p.m., Matteo leads Vincent over to his chair, as I, along with 30 or so friends and family, join him via Zoom. Earlier in the day, Matteo supervised from a six-foot distance as Vincent shaved with Matteo’s electric razor. We watch Vincent settle in, wearing his gray pinstriped suit jacket and a lime-green dress shirt, a blue surgical mask tucked under his chin. A bottle of rum sits on the side table. He leans toward the computer screen. “Wow, are all those little squares people for my party?” He stretches out his arms toward us. “My arms cannot embrace all of you, but my heart does.”

We go around offering our birthday greetings. As we take turns occupying the large screen in “speaker view,” Vincent calls out our names, clapping his hands and rearing back with surprise and delight at each new appearance. Miraculously, he seems able to both see and hear us. He takes a moment to remember some fact about each person, to elevate our reputation for the benefit of the others. I’m with my children on Martha’s Vineyard, and he asks my 13-year-old daughter how her salsa was coming along, recalling that they had danced together at another birthday party six years earlier and that she showed promise.

Then we settle in for a long extemporaneous speech. He riffs from his recent essay about how different cultures might approach the concept of social distancing. The Swedes are naturally distant people. The Puerto Ricans are not. The French have a concept called “La Distance,” where they keep strangers at arm’s length and stay away from personal subjects during initial conversations, while the Americans pepper someone they just met with questions about what they do and how much money they make. He surmises that he himself is especially well suited for quarantine since he went through it as a child. “At the end of every day, my father would bring me a small toy. If you have something to look forward to, it makes the time go faster,” he advises. Most important, he says, is to try to bring some happiness to this dark moment however you can.

Afterward, Vincent marvels at how well it all went: “I can’t think of anything I could have improved. I’m an old party-giver. To do something like this takes certain people to cooperate with one another. Nobody spilt any drinks. That’s unusual,” he says. “I spilled a lot of drinks in my time.”

*This article appears in the May 11, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!