When Marcel Duchamp exhibited his Nude Descending a Staircase at New York’s famous Armory Show in 1913, the New York Times called the painting “an explosion in a shingle factory.” At the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922, Harvard professor and literary critic Irving Babbitt described it as a book that could only have been written “in an advanced stage of psychic disintegration.”

When confronted with something new, unusual, or different, critics and the public are often quick to condemn. We shrink at strangeness, more comfortable with familiarity. We cringe at confusion, desiring simplicity. We want Shakespeare waking up one morning, putting quill to paper and, by sunset, Hamlet is born, or Michelangelo picking up a mallet and chisel one day in his workshop and, two years later David emerges, forgetting that before Shakespeare came Seneca, Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe, and that David’s genealogical tree took root 2,000 years earlier in Athens. Even The Beatles had Little Richard!

New movements in art, music, science, philosophy, in almost any discipline, typically don’t burst on the scene unannounced and ripe for critical review. Consider: the idealized faces of ancient Greek sculpture evolved into individualized portraits in the hands of the Romans. The flat facial planes in medieval paintings melted into the sfumato of Mona Lisa. The squatty stonework of Romanesque churches lifted upward into the graceful lines of Gothic cathedrals. New? Yes. Different? Yes. Unannounced? Hardly.

Mention the names of Cezanne, Renoir, Van Gogh, Monet, Matisse in almost any group of people and even those with little or no interest in art probably know that they have something to do with painting. Didn’t they do those blurry paintings of water and trees and buildings where all the colors seem to run together on the canvas? Or, Van Gogh . . . oh yeah, wasn’t he that guy that cut off his ear? Then mention Fattori, Signorini, Lega, or Abbati and all, you’re likely to get is a round of blank stares. Yet today, art scholars consider these and others in their group to be the most important movement in 19th-century Italian painting. Who were these largely unknown artists of this hard-to-pronounce movement, and what do they have to do with the French Impressionists revered the world over?

Impressionism, as otherworldly as it must have seemed when it first appeared in the 1860s, wasn’t some alien seed that dropped from outer space and took root on French soil. To understand its origins, we have to go back a bit.

For 300 years, from the 16th to the 19th century, the rules for painting and sculpture lay in the firm grip of the art academies of Europe, the principal one of which was the French Academy of Fine Arts in Paris. And it was a grip made of iron. Art was good or bad, acceptable or unacceptable, according to what the Academy said. Good art paid strict attention to the principles of drawing, composition, and use of colors as practiced by such masters as Michelangelo, Leonardo, Caravaggio, and Rembrandt. Faces, bodies, and landscape scenes were not to be painted realistically but in idealized form. Colors should be naturalistic (grass green, skies blue), and the paint surface should be smooth with no trace of brushstrokes. Subjects should be historical or mythological, and the message conveyed uplifting and intellectual. Figures in paintings, or as sculptures, should be shown dressed according to their times. The George Washington in a toga and sandals that now sits in the Capitol rotunda in Washington D.C. would have sent the French Academy into an apoplectic seizure.

Break these rules and the Academy not only blocked any opportunities to exhibit your work but stymied any chances for professional advancement and commercial success. There was only one problem: individuals rarely like being told what to do or what to like.

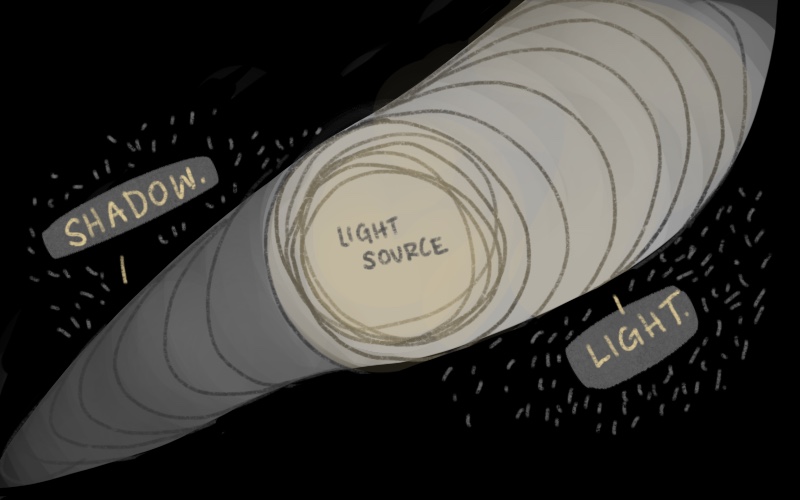

Fed up with what they considered outmoded and restrictive rules, a group of painters in France in the 1830s packs up its palettes and canvasses, closes its studio doors behind them, and begins working outdoors near the village of Barbizon. Bent on experiencing nature first-hand, these Barbizon painters, as they came to be known, paint landscapes as subjects worthy in their own right rather than as mere backdrops for scenes from mythology. Draftsmanship melts into blurred lines. Smooth finishes of paintings morph into a variety of different brush strokes and techniques. In some cases, to the horror of traditionalists, the brush yields to the painting knife. But the single greatest factor that emerges is that light becomes the governing principle in the construction of a painting.

Now go forward to the 1850s in Italy where a dozen or so young Tuscan artists are meeting regularly in the Caffe Michelangiolo in Florence to discuss art and politics. Like the Barbizon painters before them, these young Italians also have little use for what they feel are the outdated precepts of academic art. Instead of mythological scenes from Greek and Roman poetry or battle victories of conquering generals, their goal, in the words of their most famous member, Giovanni Fattori, is to paint “the impression from life,” in the Italian countryside. They too work all’aperto (in the open), making sketches on small wood panels and finishing the paintings in the studio at a later time.

A critic, coming across samples of their work in an art journal, heaps scorn on the artists, labeling them “spot-makers” or, macchiaioli, for their practice of using patches of color to construct a painting. Pronounced mah-key-aye-eee-o-li with the accent on the “o,” the word comes from the Italian macchia, for patch, spot, or stain.

While the macchia technique went in the opposite direction from that of the Renaissance masters, in one feature it conformed amazingly with Leonardo’s views on the importance of light and shadow to the painter. In one of his manuscripts destined to be part of his Trattato della pittura (Treatise on Painting), Leonardo writes that shadow and light “are the most certain means by which the shape of any body comes to be known,” that shadow and light are necessary to “excellence in the science of painting.” The guiding principle of the Macchiaioli was that shadow and light created patches of color and that these patches were the main building blocks of a painting.

Although the Macchiaioli were artists first, politics were an integral part of their movement. Throughout its long history, Italy had never been one unified country. For centuries foreign powers had been carving up the peninsula like a geographical pie of duchies, territories, fiefdoms, and small states that they ruled for their own political and economic benefit. Any sense of Italian unity had long been squeezed dry in the grasp of foreign greed and the lust for power. By the 19th century, Italians’ desire for unity under a single Italian government had bubbled up like a volcano about to erupt, fueled by the presence of Austrian troops on Italian soil. Thousands of patriotic Italians — peasants, students, professionals, the young, the old, in some cases even members of the nobility — joined local militias and underground revolutionary forces to cast out the Austrians. In this groundswell of revolt, Italy’s Risorgimento (rising again), the ideological and literary movement to liberate Italy, was born.

Several of the Macchiaioli fought in the Risorgimento, among them Silvestro Lega, Serafino De Tivoli, Giuseppe Abbati, who lost his right eye in 1860 in the Battle of the Volturno, and Raffaello Sernesi, who died from wounds suffered in 1866 while fighting with Garibaldi’s forces near Venice. Their military service earned the Macchiaioli the title of “painters of the Risorgimento.”

Eventually, through a combination of political efforts and the military successes of Giuseppe Garibaldi and his heroic “thousand men,” the Risorgimento did unite Italy. But the democratic state the people had fought and died for remained elusive. Disappointed as soldiers, the Macchiaioli went back to their paintbrushes and began creating paintings of the Italy they had known before the Austrian occupation. Concentrating on landscapes and scenes that showed the truest and most authentic aspects of Italy’s life, they hoped these pictures of the past would ignite the political reforms that, once and for all, would unite Italy into a single country.

Giovanni Fattori was the most prominent of the Macchiaioli. Born in 1825 in Livorno, his many portraits, landscapes, and military paintings were textbook examples of the macchia technique. Even though his After the Battle of Magenta won a prize and is considered to be the first Italian painting to represent an event of contemporary history, he struggled against life-long poverty. Late in his career, he was forced to give private painting lessons to survive. One of his students, Amadeo Modigliani, went on to worldwide fame. Fattori never considered himself to be a pure landscape artist. Instead, he used thousands of studies and sketches of landscapes to compose the backgrounds for his paintings of herdsmen, peasants, and woodcutters, of soldiers, encampments, maneuvers, and battles. He completed the vast majority of his paintings between 1861 and 1865 when he was in his early 40s. Fattori died on August 30, 1908, in Florence.

Telemaco Signorini, a major figure of the Macchiaioli group, was born in Florence in 1835. Writer, theoretician, illustrator, etcher, teacher, and painter, he painted primarily landscapes, seascapes, and street scenes in towns and villages in Tuscany and Liguria. In addition to his year of service in Garibaldi’s artillery, Signorini also volunteered in the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859 and afterward painted military scenes which he exhibited in 1860 and 1861. In 1883, he went to London and exhibited at the Royal Academy, where his paintings were received favorably. Signorini was also a passionate art critic. His numerous articles for art journals and two books, Cartoonists and Caricatures in the Cafe Michelangelo, and Ninety-nine Discussions of Artists, provide a wealth of information about the Macchiaioli.

Silvestro Lega was born in the Romagna in 1826. Trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, his early work conformed to the principles of academic art. But soon after he began going to the Caffè Michelangiolo in 1854, he too turned from the rigid principles of the Academy in favor of the methods of the Macchiaioli. Concentrating on intimate and domestic scenes of the bourgeois world, his The Curiosity, The Song of the Starling, and After Lunch are among the best works of 19th-century Italian art. With the onset of serious eye problems in the 1870s, he was forced to give up painting for four years. By the mid-1880s, Lega was almost blind. He died in poverty in 1894 in Florence.

Unable to achieve commercial success, most of the Macchiaioli died in penury. Never able to win over the critics and completely overshadowed by the growing fame of the Impressionists, the group melted away after 1879. Not until the first half of the 20th century did critics begin to re-evaluate their work in a more positive light, acknowledging the unmistakable hints of Impressionism that would take the world by storm a decade later.

Several of the Macchiaioli fought in the Risorgimento, among them Silvestro Lega, Serafino De Tivoli, Giuseppe Abbati, who lost his right eye in 1860 in the Battle of the Volturno, and Raffaello Sernesi, who died from wounds suffered in 1866 while fighting with Garibaldi’s forces near Venice. Their military service earned the Macchiaioli the title of “painters of the Risorgimento.”

More than 100 years after the appearance of Impressionism, Cezanne, Renoir, Van Gogh, Monet, and Matisse are names universally known and respected. Fattori, Signorini, Lega, Abbati, and others of the Macchiaioli are largely unknown outside of Italy. But art scholars have “seen the light” so to speak. The work these young Tuscans produced has now achieved worldwide prominence among critics and the public. Art scholars now recognize the work of the Macchiaioli as both leading the way in the new directions of 19th-century Italian art and as the first faint but distinct rumblings of Impressionism that would rattle the art world like a thunderclap. •