There was no fanfare when the Ministry of Sound opened 30 years ago. There wasn’t even a press release. For decades it has been one of the world’s most famous nightclubs (and one of the world’s most successful independent record labels), yet it opened almost in secret, and that was part of the plan.

Justin Berkmann was a young DJ who’d lived in New York and been mesmerised by the Paradise Garage and the mixmastery of its resident DJ Larry Levan. After the Garage closed at the end of 1987, Berkmann returned to the UK with an evangelical determination to create a club in London that was built around a similar state-of-the-art sound system. He met two people who believed in his vision: the entrepreneur James Palumbo and his business partner Humphrey Waterhouse.

Speaker stacks and dry ice in the main room, the Box. Below; a mystery DJ in the Box

I had been nightlife editor at Time Out for five years, and had reported on and photographed the explosion of acid house, Balearic beats and rave culture, but still I was caught by surprise when Ministry opened. Towards the end of 1990, I’d spoken to Berkmann about his hugely ambitious plans, but since then I’d heard nothing more. I assumed that even if they managed to achieve the near-impossible task of finding the money and the right venue, get an all-night licence, bring in New York’s finest sonic engineers to install the sound system and open a club with an alcohol-free bar, they would want their launch covered in Time Out.

A bowl of fruit on the alcohol-free bar. The club had a no-alcohol licence for its first few years

I was merely given a flyer announcing that the Ministry was opening the following weekend. Berkmann said: “I don’t want any listings; it has to be underground, strictly word-of-mouth.” Time Out would look clueless if we didn’t even mention it, so we agreed on a brief listing with a phone number for more details.

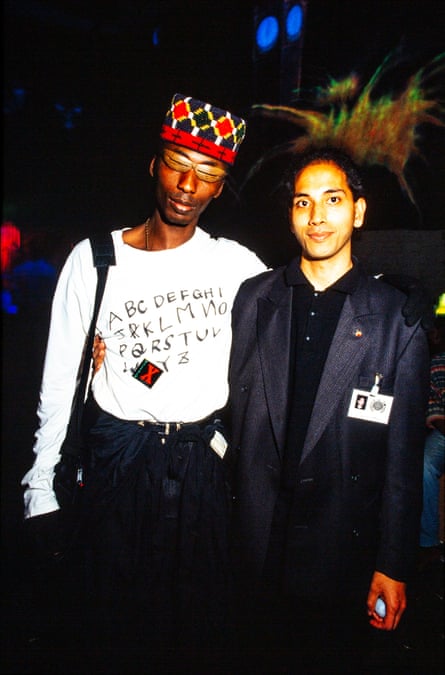

Security personnel with clubbers: David ‘Busta’ Maxwell, in black, and, on the right, Tyrone (Mr T) and Tonya

A clubber with the magician, and right – the room 2 crew. News about the new club, opened in a disused bus garage, spread largely by word of mouth

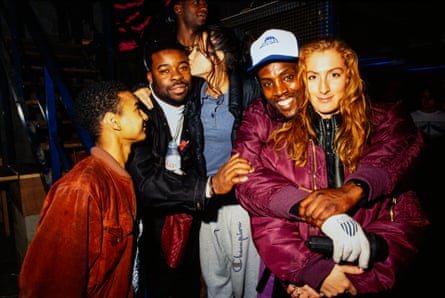

So most of the people in these photos, which were taken during the first few weekends at the club, were there because they’d been personally invited by Justin Berkmann, or knew someone who had been. “We didn’t want everyone to know when and where we were opening, so we fed the information to about 1,000 people that we had hand-picked at clubs like Legends, the Wag, the Astoria and Heaven,” he said recently. “It was about doing it from within the club scene rather than coming from above and, you know, flying over with planes and throwing out leaflets. Rather than just opening it to the public, that was the sense that I was trying to give it, of it being secret and naughty.”

Rave scene ‘face’ Anton Le Pirate, left, with friends

My first impression was that it looked like so many of the warehouses we’d raved in throughout the late 80s: utilitarian and rugged, with industrial sheet metal panels protecting the door. The security team uniform wasn’t black tie as it usually was in the West End; they wore claret-coloured MA1 jackets emblazoned with the Ministry logo. There was such a range of people in the queue in those early months – many were “proper” clubbers sporting shiny Michiko Koshino jackets or thigh-high lace-up boots, with plenty of streetwear and the occasional shellsuit (did he get in, I wonder?), while others looked far more like they might be Diana, Princess of Wales’s cousins who only ever partied in Mayfair, darling, and wouldn’t normally be seen dead anywhere near the Elephant and Castle.

Humphrey Waterhouse is the one wrapped up in the fur hat and sorting the guestlist. “He was doing everything,” recalls Berkmann. “He was doing the door, he was counting the money at the end of the evening. He was the man in the middle, playing a very cool game of keeping James the entrepreneurial businessman on board with a fairly maverick thinker who was coming up with ideas that … Well, in today’s world a lot of these ideas may have been thrown out by consultants and advisers saying ‘no, this doesn’t work or that’s too high risk’. But in those days there wasn’t anyone like that. So they didn’t really have any option but to go with what I was saying.”

Dancing beside a speaker stack. Many of the clubbers at these early nights were personally invited by co-founder Justin Berkmann

The most obvious example of this was that nearly all of their money, around half a million pounds, was spent on the sound system, and on making the main dancefloor, The Box, soundproof and just about bomb-proof according to Berkmann. “We’d built what was fundamentally a nuclear bunker. It was the most absurd construction, but it was done so that no one could ever come along and close us [because of noise pollution]. That’s why we only had about three lights in the club, because we completely ran out of money.”

Lynn Davis, the architect, had to improvise with next to nothing. “That’s why the bar was made of poured concrete. Necessity was the mother of invention, so the toilets looked like something you’d find in a shantytown, built with scaffolding and thick plastic sheeting, with guttering for the urinal.”

Speaker stacks … and white jeans

The amazing sound system – or at least the six-speaker arrays that were the most visible and audible elements of it – was my primary focus, as it seemed to tell the story in one image. I took so many shots of the clubbers around the speaker stacks. Some people were understandably pissed off by me and my flash gun, but in those days of analogue film you could never be entirely sure that you’d got the shot.

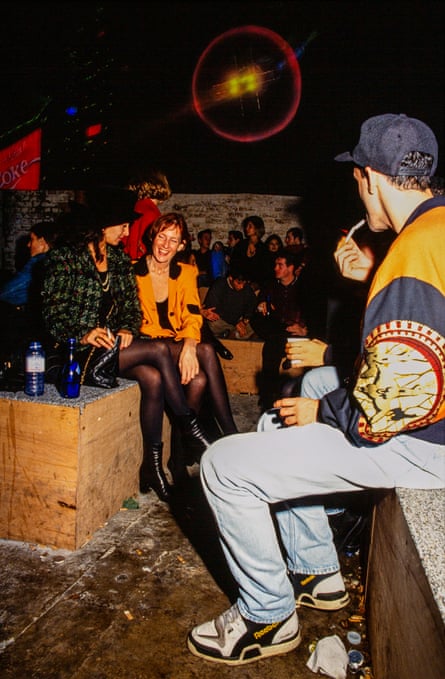

There was also the huge bar where no alcohol was served, which is why the photos feature bowls of free fruit and bottles of Lucozade and Purdey’s – and that’s how it remained for about three years until the club finally got an alcohol licence in 1994.

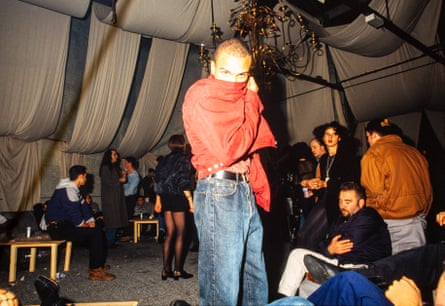

Chilling in the VIP room

The Ministry followed the Paradise Garage template in having a small film room from day one, with movies like Apocalypse Now and Blade Runner screened throughout the night (it was also known as the Snogging Room). New York’s Paradise Garage didn’t have a VIP room, and Berkmann says he’s no fan of the concept, but he was reassured time and again that a London club had to have a VIP area. “There are times during a night out when you want to be silly and other times when you want to be serious,” he says. “The Box is a serious room; it’s a place you get lost in the music. That may not necessarily be something you want all night, and what I loved at the Paradise Garage was that there were rooms with different vibes and different levels of energy and emotion.”

What happened in the VIP room didn’t relate to what was happening elsewhere

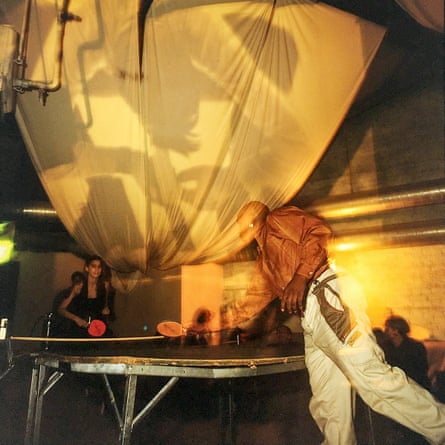

… there were magicians and table tennis

The VIP room in the Ministry was essentially independent; what happened there didn’t relate to what was happening elsewhere at all. Musically, they’d play anything from Abba to Sinatra, whatever music the guests would relax to, because it was a place to kick back and chill out on the sofas. “In the VIP it was ‘trash’,” says Berkmann. “It wasn’t that the music was rubbish – it was that it wasn’t ‘serious’, like in The Box. It had a sense of humour, for the people who wanted to go out there and be silly.”

Also up in the VIP room was a table tennis table that Berkmann recognises as “my own table tennis table from my childhood home. It only lasted about a month, so these photos were taken in the very early days”. I even saw a magician who’d been hired to entertain people in the queue, working his tricks for the VIPs who certainly weren’t all celebs but a mix of club and music industry types, Sloanes, sport stars and the usual array of lucky chancers.

“I’ve had so many people come up to me and say, ‘I met my wife on the dancefloor at Ministry of Sound and now we’ve got three children,’” Berkmann laughs. So how many children have been produced because of Ministry? “It’s got to be in the hundreds at least. There’s a small clan of children that have been created from their parents meeting while off their tits.”

Ministry of Sound Classical presents Three Decades of Dance, is at the O2 Arena, London, on 13 November, featuring Paul Oakenfold. Later on Saturday, Justin Berkmann headlines at the Ministry of Sound for the first time since 1992.