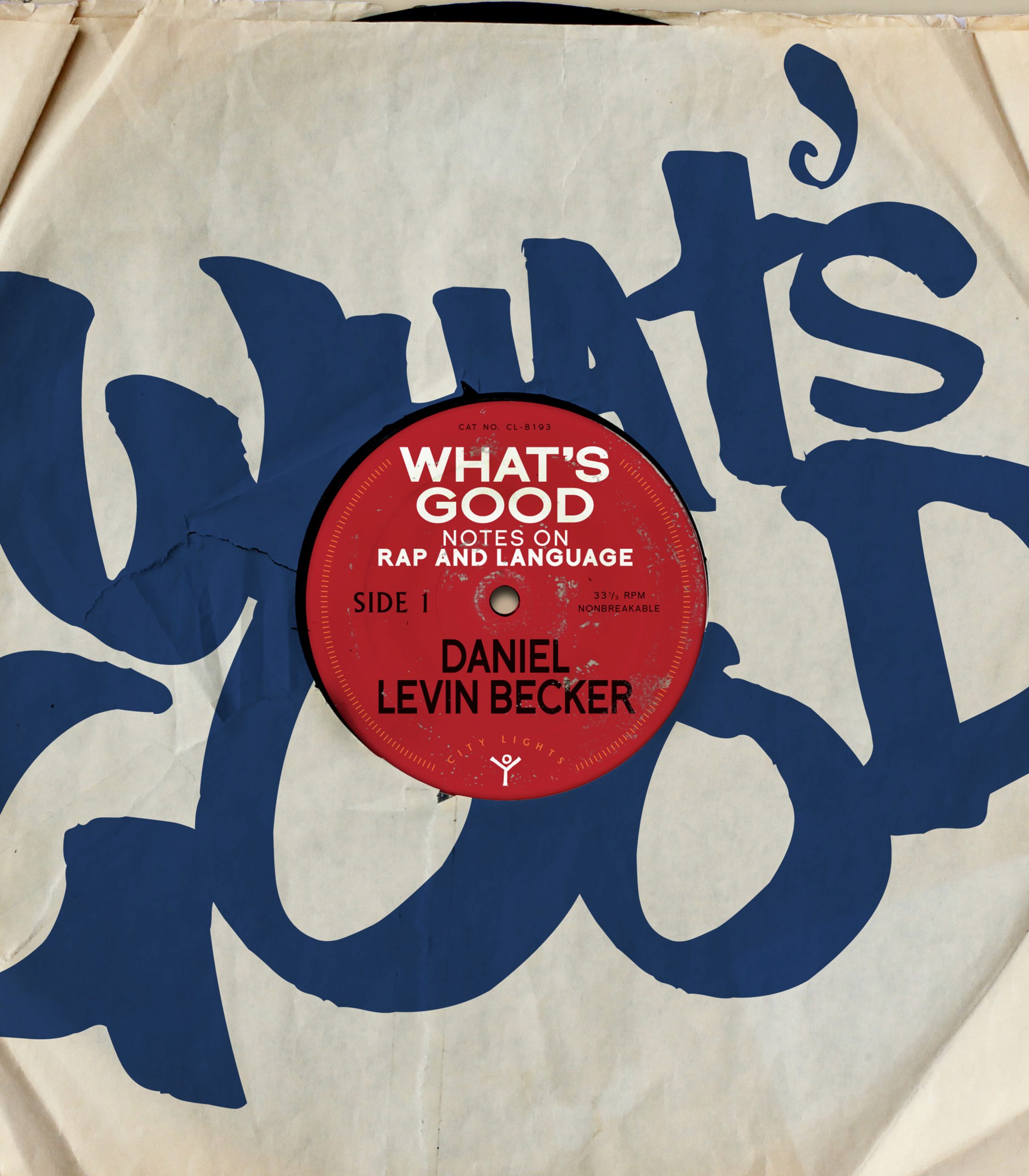

Excerpt: 'What’s Good: Notes on Rap and Language' by Daniel Levin Becker

Jade McClelland: Bonnaroo 2010 / Jay-Z, 2010 (CC)

Jade McClelland: Bonnaroo 2010 / Jay-Z, 2010 (CC)

Writing/biting

If you having girl problems I feel bad for you, son

I got ninety-nine problems and a bitch ain’t one— Ice-T, “99 Problems” (1993)

My guess is that if there’s a voice saying these lines in your head it belongs to Jay-Z, excitable and hoarse, cruising over that rip-roaring Rick Rubin beat. His towering “99 Problems” came out in 2003 and was so ubiquitous for the remainder of the decade that I don’t think it will ruffle any feathers to call it its own apparent endpoint of rap’s rhetorical continuum: a commonplace, a catechism. But none of this changes the fact—and I’m not ruling out the possibility that you’re aware of said fact, even if the voice in your head still belongs to Jay-Z—that Ice-T said the same words, in the same order, arguably more dopely, ten years earlier.

Upon closer inspection—I didn’t know this for a long time— Jay’s “99 Problems” is a bit of a patchwork. In addition to borrowing the chorus from Ice-T (Chris Rock’s idea, according to Rubin), Jay lifts the beginning of the third verse verbatim, give or take a word or two, from UGK’s “Touched,” and his writeoff just after that of an effete dude—You know the type, loud as a motorbike, but wouldn’t bust a grape in a fruit fight—a little more subtly from LL Cool J’s tacit MC Hammer dis in 1990’s “To Da Break of Dawn”: Shootin’ the gift but you just don’t shoot it right / You couldn’t bust a grape in a fruit fight. All of this is uncredited, even in Jay’s memoir and lyric book, Decoded, whose annotations for “99 Problems” cover only the second verse.

Now, to quote Slick Rick in “La Di Da Di,” a song itself arguably eclipsed by Snoop Doggy Dogg’s wholesale cover version and liberally sampled elsewhere, This type of shit it happens every day. “One can make the argument that rap—like China—is a space where plagiarism simply doesn’t exist,” writes Ariel Schneller at Genius. Repetition with a difference is in the nature of signifying, the black rhetorical tradition in which rap has always inscribed itself, and who’s to say changing a couple of conjunctions doesn’t constitute difference?

Nonetheless: this is kind of a lot. Jay-Z, it turns out, does this almost-identical rhyme-cadging thing often enough to blur that already faint line between creation and copying. How much of Biggie’s rhymes is gonna come out your fat lips? asked Nas, back when he and Jay were feuding. Cam’ron, who’s also logged his share of time beefing with Jay—he once savaged him for wearing jeans with open-toed sandals, then likened his appearance to that of Joe Camel, Fraggle Rock, and Alf—tallies many of Jay’s interpolations of rhymes from Biggie and Slick Rick and Snoop Dogg and Nas and Big L on a circa-2006 track called “Swagger Jacker.” Between each audio exhibit of evidence—Jay’s rhyme, then the conspicuously similar original—you hear a scribble of tape-rewind, a reverb-drenched sound effect of someone chomping into an apple, and then Jay saying I’m not a writer, I’m a biter, a doctored version of this line—

I’m not a biter, I’m a writer, for myself and others

I say a Big verse I’m only biggin’ up my brother

—from a song called, ironically enough, “What More Can I Say.”

The second half of that couplet is in line with the way Jay generally explains his various borrowings from Biggie, who was a close friend of his: “Doing that was my way of always keeping him fresh and keeping his music fresh on everyone’s mind.” (In a 2010 New Yorker “Talk of the Town” vignette Cornel West recalls Jay telling him and Toni Morrison he’s “been playing Plato to Biggie’s Socrates.”) And some of the time this does come across as a perfectly tenable argument: for instance on the 2011 smash “Niggas in Paris,” when he says I’m liable to go Michael, take your pick / Jackson, Tyson, Jordan, game six as a riff on Biggie’s 1998 I perform like Mike / Any one: Tyson, Jordan, Jackson. Or when he takes Biggie’s syllable-chopping flex from 1997, My sycamore style, more sicker than yours, and unfurls and dissects it in 2003 as

I was conceived by Gloria Carter and Adnis Reeves

Who made love under the sycamore tree

Which made me a more sicker MC

This is repetition with a difference: recognizably related to the prior iteration, unambiguously an echo, but carrying its own narrative, its own distinct context. But then there’s the part in “Girls, Girls, Girls, Pt. 2” where he reprises Biggie’s boast about juggling multiple lovers without getting caught—

Isn’t this great, your flight leaves at eight

Her flight lands at nine, my game just rewinds

—by changing it, somewhat confoundingly, to

Isn’t this great, my flight leaves at eight

Her flight lands at nine, my game just rewinds

Or when he picks up a couplet from Slick Rick’s “The Ruler’s Back”:

Now, in these times—well, at least to me

There’s a lot of people out here trying to sound like Ricky D

and sets it back down in his own “The Ruler’s Back”:

Well, in these times—well, at least to me

There’s a lot of rappers out there trying to sound like Jay-Z

Again, Jay’s far from the only rapper to appropriate quotations and change a bare minimum of details—now to well, and to but, out here to out there, hit it! to hit me!—as though scrupulously dodging a YouTube copyright protection algorithm. But if he does it a little too much to ignore, he also never seems to pause to give credit, even when the opportunity overwhelmingly presents itself. In Decoded he explains of his 2003 My homie Sigel’s on a tier where no tears should fall that “the homonym of tiers and tears connects prison tiers with crying—but you can’t cry in prison (at least not out in the open),” but neglects to mention that Chuck D used an identical pun in 1988.

So what’s this about? Is it pure unabashed mimicry, like Puff Daddy pillaging pop hits from the eighties but without the expensive sample clearances? Or is it possible that the repetition is itself the commentary? Notice, if you will, some of the borderline-gaslighting places it happens: when he replaces Ricky D with Jay-Z in a line that’s already about soundalikes and copycats; when he changes Chuck D’s first-person prison dispatch to a third-person one about his affiliate Beanie Sigel; when he uses like to compare himself to any number of famous Michaels. Could it be that my game just rewinds is not a brazen admission of petty thievery—i.e., my game is literally nothing but running back other people’s tapes—but a boast that he’s roping all these echoes into a historically circuitous game of his own magisterial devising?

Nothing gets a certain species of extremely online rap fan exercised like such questions, and I’ve seen both positions compellingly and stridently defended. (I’ve also heard a “Swagger Jacker”–style compilation of Cam’ron’s own borrowings.) Jay is clearly talented enough that he doesn’t need to do this, goes one argument, so why would he do it if not in good faith? He’s talented enough that he doesn’t need to do this, goes another, so why does he do it at all? One forum poster expresses annoyance at the negative karma that accrues back to him when he tells his friends that Jay’s cleverness isn’t really his. In that case, wonders someone else, isn’t your beef with your friends? “Jay-Z is respecting Biggie by interpolating the narratives,” writes Schneller at Genius, “regardless of whether every suburbanite white kid who dances along to ‘I Just Wanna Love U’ appreciates the reference.”

What’s this about, this compulsion to ensure that suburbanite white kids get the reference, to disabuse your friends of their tragic illusions about the purview of Jay’s originality? Why don’t the people who do this seem to spend any energy on redressing the wrongs done to the rappers quoted without credit? I’d love to believe this is something like the extremely online rap fan’s version of doing the knowledge, that Five Percenter ethos of building by sharing out loud, showing and proving what you know. But I don’t believe that’s what it is, not really. I think it’s more likely suburbanite white kids all the way down, competitively policing the historical record on behalf of imagined novices because that’s somehow less daunting than admitting we’ve still got gaps in our understanding too.

This, I think—more because of the internet economy and its pernicious sales levers of controversy and gamification than out of any direct philosophical intent—is why Genius inevitably matured from a collaborative educational resource into yet another playing field for performative erudition, with IQ points and leaderboards and whatnot. So it often goes for communal knowledge work on the internet: in a discursive space where veteranship and cred are the supreme capital, you’re only ever a couple of degrees away from someone overtly arguing that there’s such a thing as too much interpretive liberty.

But that implication is ultimately extrinsic to hip-hop itself, which like any signifying tradition creates in-groups and out-groups through destabilization and insinuation and if-you-know-you-know swagger. If I never hear, say, Jurassic 5 fans grousing about uncredited borrowings or fretting about other people missing references—if J5’s song pages on Genius are ghost towns compared to Jay-Z’s—maybe that’s because those fans haven’t yet accumulated enough of that capital to worry about protecting it. Or maybe it’s testament to the old-school values Jurassic 5 and kindred acts have worked so openly to keep alive, where it’s about liberty and inclusivity rather than material or intellectual wealth, where you can join the in-group without knowing its codes in advance. Maybe those boil down to the same thing. Signifying, remember, is at base about punching up, not down.

*

Though Jay doesn’t mention in Decoded that he took the hook of his “99 Problems” from Ice-T’s, he does explain that he’d been criticized for his use of the b-word elsewhere, so included but a bitch ain’t one as “a joke, bait for lazy critics. At no point am I talking about a girl.” His rationale, that if you follow the narrative through the song’s three verses the word refers to critics, female dogs, and effeminate men respectively, is convincing if you squint hard enough. In Ice-T’s “99 Problems,” on the other hand, the word refers to women relentlessly, unabashedly, pornographically:

I got a bitch with a mink who rocks a fat gold link

Who likes to fuck me with her ass up on the kitchen sink

Got a bitch with tits, a bitch with ass

A bitch with none, but hey, I give her a pass

“I think that being a player, a real live player, there’s nothing you like better than to give props to other people,” Ice-T shrugged when asked to comment about the uncredited use of his refrain in the Jay-Z hit. “That’s just what you should do. But… you know. That’s just how I get down.” Not long after this he released a new version of his own “99 Problems” with Body Count, his metal band. “A lot of journalists thought that was Jay-Z’s record, and I was like, Aha, gotcha!” he later told an interviewer. “It was just something I threw on there as a booby trap for journalists that think they know a lot, so they can just, like, as we say—you can edit this—step in some shit they can’t get off their shoe.” Booby trap for journalists, bait for lazy critics. Game rewinding.

About the Author

Daniel Levin Becker is a critic, editor, and translator from Chicago. An early contributing editor to the groundbreaking lyrics annotation site Rap Genius, he has written about music for The Believer, NPR, SF Weekly, and Dusted Magazine, among others. His first book, Many Subtle Channels: In Praise of Potential Literature (Harvard UP, 2012), recounts his induction into the French literary collective Oulipo.

Publication Rights

“Writing/biting” from What’s Good: Notes on Rap and Language c.Copyright © 2022 by Daniel Levin Becker. Reprinted with the permission of City Lights Books. www.citylights.com. The text was altered slightly for this excerpt.