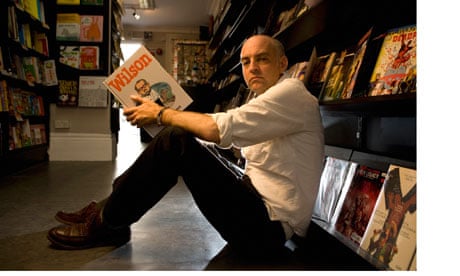

The night before I meet Daniel Clowes, comic-book writer extraordinaire, I go to see him on stage with Chris Ware, author of the prize-winning graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid On Earth. To say this is a hot gig is a wild understatement – it's the comic equivalent of seeing the Smiths and the Stone Roses on the same bill – and the place is packed with groovy young things in architectural spectacles and patterned, thrift-store shirts. But the real surprise is that, beneath the lights, Clowes and Ware make for such a hilarious double act. Ware, who looks like Frasier Crane, only with an even bigger "brainiac" forehead, has a devastating line in self-deprecation. Clowes, meanwhile, is long of leg and bald of head, and, curled in his chair, looks like the angst-ridden star of an indie movie – one set in Brooklyn, probably, with a plotline involving therapists and unattainable women. Until, that is, he opens his mouth, at which point you crack up. Everything he says is dry and knowing. Plus, he laughs at his own jokes. I love a man who laughs at his own jokes.

In the theatre, I wonder if this tic is down to nerves. But, no. The next morning, he titters just as boyishly when we talk about his new book, Wilson, the story of a lonely, middle-aged, egotistical loner who simply cannot get on with other people, no matter how hard he tries. In some ways, Wilson is a wholly unsympathetic character, saying aloud the things others might only think. But he's also an everyman figure: there's a bit of him in all of us, and this makes him funny. In one scene, in an airport lounge, he strikes up a conversation with a business traveller. He asks the man what he does. When the man starts to explain – he's in senior management at an equity firm – Wilson waves a finger across his own frozen facial features, and says: "Glaze!" The man continues. "Jesus," says Wilson, increasingly exasperated by his mumbo jumbo. "Listen to me, brother," he finally explodes. "You're going to be lying on your death bed in 30 years thinking: 'Where did it all go? What did I do with those precious days?' Some shit-work for the oligarchs, is that it?"

Clowes is mildly surprised by the reaction to Wilson so far: though the book is selling faster than any other he has written, the responses to it have been "all over the map". Personally, he thinks those who have Wilson down as a misanthrope are entirely wrong.

"I know lots of misanthropic types," he says. "I tend to like them. I find it sort of healthy, comforting. It's a better default setting than over-optimism. But I don't think of Wilson as misanthropic. He thinks he's going to make a connection with people, that they'll be on his wavelength, and then gets frustrated when they aren't. But he doesn't go into it thinking: look at this jerk! He has a naive faith in humanity. I guess there's a certain kind of person who can't relate to him in any way. People seem to need a likable protagonist more than ever. It's because they're so used to being fed that in the movies. I find it insulting, the way movies try to ingratiate themselves with the audience that way. I'm more interested in characters who are a little difficult."

He can say that again. Difficult characters are his stock in trade. In 2001 Clowes became unexpectedly famous (at least by the standards of most cartoonists) when his book Ghost World, about two social outcast teenagers, was turned into a hit movie starring Thora Birch and Scarlett Johansson. He wrote the screenplay, and was duly nominated for an Oscar. There followed two more unsettling graphic novels (he dislikes this term, but accepts that he has been unable to come up with anything better), David Boring and Ice Haven. All these books have strange, often adolescent protagonists to whom weird and grotesque things happen almost by accident, casually disturbing their otherwise suburban lives – and also a certain sense of timelessness and placelessness (this is an America we recognise, yet it is not real, and its cities are rarely named). Clowes's work has since been compared with that of Philip Roth and JD Salinger, and, in 2005, Time magazine named David Boring one of the 10 best graphic novels ever written. Asked to describe this book in a single sentence, its author quipped: "It's like Fassbinder meets half-baked Nabokov on Gilligan's Island." He wasn't entirely joking.

Wilson, however, has a slightly different feel. In it, Clowes uses the single-page gag format – each page has a punchline, as well as working as part of the longer narrative – and it has a more elegiac, redemptive tone, perhaps because he began work on it as he sat beside his dying father's hospital bed.

"It's this horrible limbo," he says. "You're there, waiting for the inevitable, but you don't want to leave. I was hoping to have some connection [with my father], but he didn't want to talk; he was thinking his own things. So, I got out my little sketch book. I thought: I've got to do something primal, something automatic, the first thing I can think of. That was when Wilson came to me: I saw him in the airport. He was one of those rare characters who just appears like a lightning bolt. I knew this guy. He's the kind of character who creates his own content. Give him, say, the subject of sparkling water versus non-sparkling, and he'd have something to say – though what, exactly, might surprise me. He was beyond my control, that's the thing. He said what he wanted to say."

Clowes was born in 1961, in Chicago, and, according to his mother, never wanted to be anything other than a cartoonist. "My parents divorced," Clowes says, "and my brother, who's 10 years older than me, moved out when he was fairly young and left me all his stuff. He was an inveterate collector of comics. I had no television when I was little, just a stack of old, beat-up comics from the 1950s and 1960s. And then he'd come home, bringing with him underground comics. I was inundated! I learned the language of comics at three or four. It was innate to me."

At art school, it was frustrating: his teachers insisted that cartooning was an "undignified" field. "And they were right! Nobody was doing adult comics, then." So how did he keep himself when he graduated? "A friend of mine was made editor of Cracked magazine, the poor man's Mad. I worked on that, and I did my first comic book series, Lloyd Llewellyn. But the truth is that for ages it was just me, a rented room and a drawing board. I had to work obsessively hard to get out enough issues of Lloyd, and then of Eightball [in which Ghost World and David Boring were first serialised], to make even a bare living. I was 30 before I made a living that was not embarrassing."

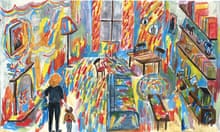

These days he is married, with a small child, and his drawings regularly adorn the cover of the New Yorker. What's more, graphic novelists have joined the literary establishment. Only yesterday, Clowes was walking around the offices of Jonathan Cape thinking how amazing it is that, in Britain, he now shares his publisher with Philip Roth and Ian McEwan. "I just kept going: wow!" This is a happy state of affairs, but it worries him that younger writers now think of cartooning as an instant career. The comics he reads by up-and-coming artists are super-professional, but they are also, he says, instantly forgettable; he has yet to discover anyone with the indelible talents of, say, Robert Crumb or Adrian Tomine.

"It's not like a job at Microsoft," he says. "You've got to be obsessed. Now there are all these people who are not really comic people doing graphic novels. Well, it's not that easy, actually! I wouldn't pretend to think I could suddenly write a novel. Screenwriting is the closest thing to it, because a comic book is all about dialogue. Even so, I felt like an amateur when I started that."

Is he still writing films? Yes, though it's a tough time. He believes the edgy Ghost World would almost certainly not get made today: as belts have tightened, it has become increasingly hard to raise money for anything other than the most obviously commercial films. He has five or six projects on the go, but none has a director on board so far, and his cherished film about a group of kids who remade Raiders of the Lost Ark frame by frame will not now be made. "I wrote a draft, and I could tell that everyone was really engaged with it. But then they decided to go and make the fourth Indiana Jones film – even though Harrison Ford is, like, 84 – and the studio began to worry about anything that might infringe on their huge franchise."

For a while, Clowes was the world's only Oscar-nominated cartoonist. No longer. In 2008, Iranian graphic novelist Marjane Satrapi received a nomination for best animated feature for the film of her memoir, Persepolis. But best not to get too hung up on these things. "It was a weird time. You get invited to these lunches, and you're sitting next to Mel Gibson, or whoever. They look at you as if to say: who the hell are you? Though they're careful to be nice in case you're some big producer. You realise it's all a bit insincere. I guess I get to be the guy who reports this back to the world: I need to do a comic book about it." So far, as gatherings go, he prefers events such as the comics convention he has just attended in Denmark, where he got to hang out with Ware and Charles Burns, author of the award-winning Black Hole. He says they all had a great time.

I don't disbelieve him. But I can't help but wonder why – given that Clowes is so very smiley and his colleagues all so very sociable – every graphic novel I've ever read has been full of alienation and angst.

"Well," he says, "think about the job. It only attracts a ... certain kind of person, really. It's hard, and solitary. We only come out periodically. You've got to write for four hours a day, and even then you're not done, because you've still to draw the panels. It's so labour intensive, and you can't work with anyone else because every time they sharpen their pencil, it sets your teeth on edge." He laughs. "I once worked with a friend over the summer. He would sit there silently, and then, every so often, he would go: 'Godammit!' I was waiting for that burst of anger the whole time."

These days, he works at home, where there are only his own outbursts to deal with.