Moby Dick is a wonderful target for critics who like to identify the books that Melville plundered…

From Lapham’s Quarterly:

Who Herman Melville was and what he actually thought about anything are altogether unsatisfying questions that have never been answered in a satisfying way. This has led critics from the beginning of his literary existence to accuse him, often rightfully, of fraud. The proper answer to such criticism is that all literature is a species of fraud, in the same way that all property is theft, and every great fortune is founded on a great crime. As Cormac McCarthy once said, “The ugly fact is that books are made out of books.” The fact that McCarthy, author of Blood Meridian and other novels, stole the sentiment from William Hazlitt doesn’t make it any less true.

The fact that Moby Dick is the philosopher’s stone of American self-reflection makes it a wonderful target for reviewers, critics, and scholars who like to identify the books that Melville plundered, a good number of which are helpfully identified by the author in the novel’s prefatory extracts (supplied by a “Sub-Sub-Librarian”). “Give it up, Sub-Subs!” the author exhorts. But why should they? It’s fun to play games with whales and history. What they miss, of course, is that the fact that Melville’s literary career was born in fraud and realized its true greatness in the writing of Moby Dick is not a coincidence: Melville spent his entire writing life pondering the line that separates imposture from invention, and worse. Just as books are made of other books, every great American is a person who made themselves up out of whole cloth. So how else could a homespun American Shakespeare have happened, and what else could he have pondered, if not the frauds that define America and Americans?

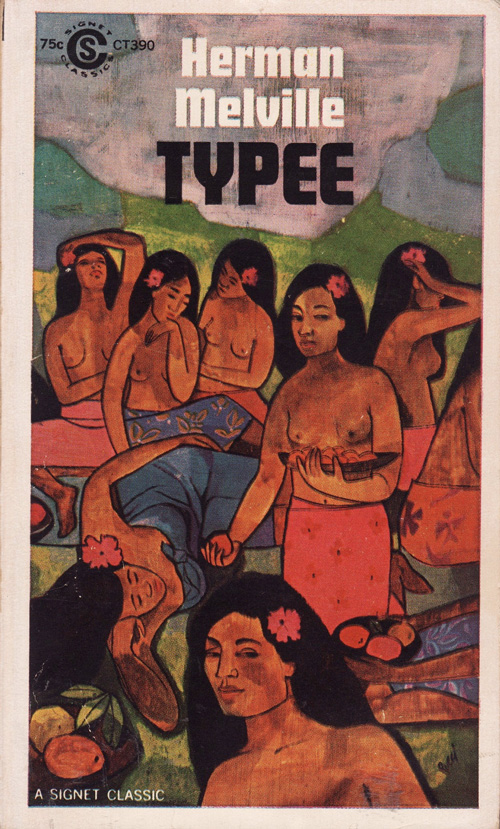

Melville’s first book, Typee, the author’s account of his time among the Polynesians, made him famous; it was easily his most successful work during his lifetime. The new editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Walt Whitman, wrote an unsigned review pronouncing it to be “a strange, graceful, most readable book.” Whitman also noted a resemblance to contemporary seafaring tales, including an 1831 account of a shipwreck in the Caribbean Sea. Whitman’s nose for the magpie elements of Melville’s text wasn’t matched by two distinguished New England reviewers, who weren’t interested, or didn’t notice, or were too polite to say. In a signed review in the Salem Advertiser, Nathaniel Hawthorne, who had no personal taste for adventures, announced that the “book is lightly but vigorously written; and we are acquainted with no work that gives a freer and more effective picture of barbarian life.” Thoreau read Typee at Walden Pond, and appears to have understood the book as a valuable outline of experiments in living that had been successfully tested by Polynesian islanders.

To say that Typee is a book made out of other books doesn’t mean that Melville himself never sailed on the Acushnet, or that his account of his life among the Polynesians is devoid of truth in every detail.