Weathering Heights

From The New Yorker:

“No weather will be found in this book,” Mark Twain declares in the opening pages of his 1892 novel “The American Claimant.” He has determined to do without it, he explains, on the ground that it usually just gets in the way of the story. “Many a reader who wanted to read a tale through was not able to do it,” he writes, “because of delays on account of the weather.”

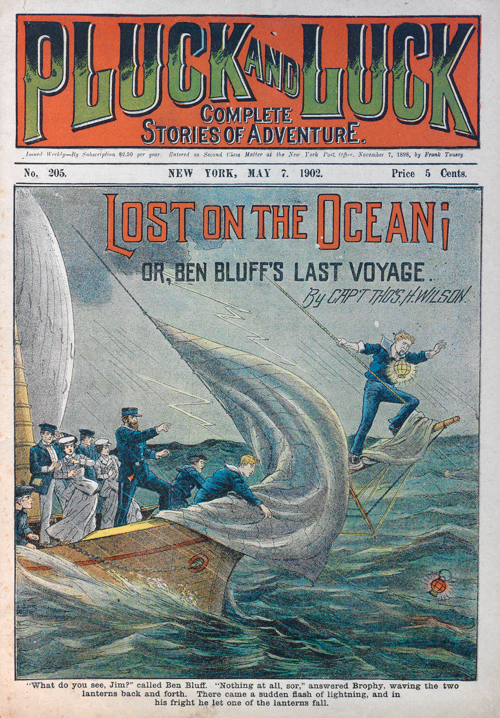

Twain was not alone in mistrusting meteorological activity in fiction. As literary subjects go, weather has a terrible reputation. More precisely, it has two terrible reputations that do not get along. On the one hand, weather is widely regarded as the most banal topic in the world—in print as in conversation, the one we resort to when we have nothing else to say. On the other hand, it stands perpetually accused of melodrama. “It was a dark and stormy night,” begins Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1830 novel “Paul Clifford,” which goes on to invoke torrential rain, gusting wind, guttering lamplight, and rattling rooftops: weather as plot, setting, star, and supporting cast of what is, by broad consensus, the worst sentence in the history of English literature.

Melodramatic or banal prose mostly gets blamed on the author, reasonably enough. But melodrama and banality are aesthetic judgments, and, as such, they are sometimes also products of their context. Twain was writing in the late nineteenth century, a time when the field of meteorology was belatedly coming into its own. With that scientific model of weather in ascendance, the literary models came to seem suspect. Weather facts served to make weather fictions seem overwrought, while the newly empirical understanding of the atmosphere—and, more staggering at the time, the ability to predict its behavior—made weather itself seem suddenly more prosaic.

That was the context in which Twain joked about eradicating weather from his work. But even he conceded that “weather is necessary to a narrative of human experience.” Through the ages, we have used weather in our stories to illuminate the workings of our universe, our culture, our politics, our relationships, and ourselves. Before “The American Claimant” was published, sans weather, you might as easily have searched the canon for a novel without adverbs. Twain was likely correct when he called his weatherless book “the first attempt of the kind in fictitious literature.”

Twain died in 1910, too soon to discover that his joke turned out to be borderline prophetic.

“Writers In The Storm”, Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker (Via)