Remembering John Ashbery (1927-2017)

Portrait of John Ashbery, Larry Rivers, 1962

by Andrew Epstein

This past Sunday, September 3, brought the very sad news that John Ashbery had passed away at the age of 90. Ashbery has long been regarded as the greatest and most influential living American poet, so it is not surprising that the last few days have seen an outpouring of grief and praise from all corners of the literary community, and a slew of fine obituaries and tributes (I’ve collected many of these below). I was grateful that The New York Times also asked me to suggest a few favorite shorter poems to accompany their obituary for Ashbery, which you can see here.

Even though he had just turned 90 in July, it somehow felt as if Ashbery would always be here, like crazy weather (“falling forward one minute, lying down the next”) – churning out a new book every year or two, exhibiting his wonderful collages, blurbing younger poets, generally filling the air of contemporary poetry with his brilliant presence. So his loss still came as a shock, a sharp blow, despite his extraordinary, long career and full life.

One reason Ashbery’s death seems so significant and painful is that it marks the real end of an era: he was one of the last of the great figures associated with the adventurous, avant-garde movement that emerged after World War II known as the ‘New American Poetry.’ And more broadly, he was one of the final living poets belonging to the amazing generation born around 1925 to 1927, a roster of illustrious names that includes Kenneth Koch, Jack Spicer, Frank O’Hara, James Merrill, James Wright, Adrienne Rich, Robert Creeley, Allen Ginsberg, A. R. Ammons, Galway Kinnell, and many more.

Ashbery was also, of course, one of the last surviving members of the New York School’s legendary first generation. He outlived virtually all of his original close companions: Frank O’Hara, who died 51 years before him, Fairfield Porter, James Schuyler, Kenneth Koch, Larry Rivers, Barbara Guest, Jane Freilicher, Harry Mathews – they all went into the world of light before Ashbery himself, a poignant fact that often surfaced subtly and wistfully in his later work.

Because Ashbery is such a towering figure, I’ve found it hard to know where to begin or what to say that would be adequate to mark his passing. On a personal level, his work has been of such vital importance to my own writing and thinking for so long that his loss seems too huge to encapsulate or sum up, so I’ve decided I’m not going to really try here.

It did occur to me, as news of his death sank in, that I’ve been reading and writing about Ashbery continuously for 25 years and that his “philosophy of life”; his sensibility and sui generis voice; his distinctive, hilarious, tragic and consoling way of looking at the world and its absurdities and pains; not to mention countless beautiful, moving, and strange lines of his poetry have all seeped into my consciousness, quietly affecting how I think and relate to my own experience in ways I can’t really articulate.

At one moment in “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” Ashbery happens to reflect on this very process: how “the light or dark speech” of others – include those we read deeply – enters our minds and becomes woven into the fabric of our selves:

How many people came and stayed a certain time,

Uttered light or dark speech that became part of you

Like light behind windblown fog and sand,

Filtered or influenced by it, until no part

Remains that is surely you.

As an undergraduate at Harverford College in 1991, I took a bus over to nearby Bryn Mawr College by myself one evening to see Ashbery read from his new book-length poem Flow Chart, in a dim, grand hall, and came away equal parts mystified and inspired. A few years later in graduate school at Columbia University, I had the good fortune of working closely with one of Ashbery’s closest friends, Kenneth Koch. The first day I met Koch and began working as his assistant, he immediately informed me, half-jokingly, that Ashbery was his “greatest living rival,” and quickly convinced me that no poet was more important or better than Ashbery, whose work he absolutely revered.

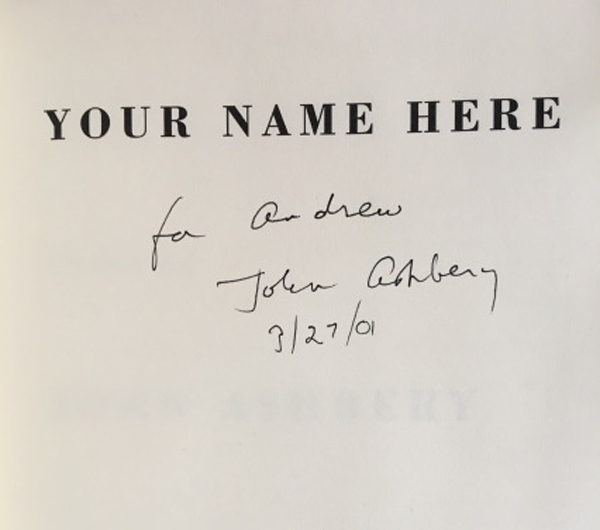

Your Name Here

I studied Ashbery’s poetry in my courses, wrote seminar papers on his work, and eventually decided to make him one of the main subjects of my doctoral dissertation (though Koch did half-jokingly wonder why I wasn’t focusing on him instead). One of my first published reviews was a piece about Ashbery’s book-length poem Girls on the Run, which appeared in the American Book Review in 2000. Ashbery’s work was at the center of my first book, Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry, which delved into his ideas about the self, interpersonal relationships, and his philosophical connections to Emerson and American pragmatism, and explored the close, complex personal and poetic “sibling bond” at the heart of his relationship with Frank O’Hara. More recently, I contributed a chapter about Ashbery for The Cambridge Companion to American Poets and then, just a couple weeks ago, my review of Karin Roffman’s new biography of his early life appeared in the New York Times Book Review.

Not surprisingly, Ashbery has also been a regular fixture on my humble blog about the New York School – in fact, I realized I’ve written 100 posts about, or at least touching on, Ashbery since I began the site in 2013. (To sample some of these posts – which range from pieces about important Ashbery poems like “Pyrography” or the time Ashbery smoked a joint with Elizabeth Bishop to the recent show where Patti Smith paid tribute to “my Ashbery year”, see here).

I’m sure there will be many more, just as there will always be more essays and books devoted to Ashbery’s poetry, just as there will always be young writers who will revel in his influence and be fueled by his spirit as long as there are poets writing poetry. For now, there is the sustaining tower of books and words he left behind.

“You have built a mountain of something,

Thoughtfully pouring all your energy into this single monument”

For it all builds up into something, meaningless or meaningful

As architecture, because planned and then abandoned when completed,

To live afterwards, in sunlight and shadow, a certain amount of years.

Who cares about what was there before? There is no going back,

For standing still means death, and life is moving on,

Moving on towards death. But sometimes standing still is also life.

And here, finally, is Frank O’Hara’s beautiful, now extra-heartbreaking 1954 poem “To John Ashbery,” in which he imagines himself and “Ashes” (his affectionate nickname for Ashbery) reading their “new poems to each other / high on a mountain in the wind,” like a pair of ancient Chinese poets.

To John Ashbery

I can’t believe there’s not

another world where we will sit

and read new poems to each other

high on a mountain in the wind.

You can be Tu Fu, I’ll be Po Chü-i

and the Monkey Lady’ll be in the moon,

smiling at our ill-fitting heads

as we watch snow settle on a twig.

Or shall we be really gone? this

is not the grass I saw in my youth!

and if the moon, when it rises

tonight, is empty —a bad sign,

meaning “You go, like the blossoms.”

Rest in peace, Ashes, little J.A.

*

Here is a selection of obituaries and tributes that have begun to appear since Ashbery’s death:

New York Times obituary by David Orr and Dinitia Smith (along with a selection of Ashbery’s poems, selected by Gregory Cowles and myself)

Mark Ford’s obituary for Ashbery in the Guardian

Dan Chiasson in the New Yorker

Matthew Zapruder in the San Francisco Chronicle

Larissa MacFarquar in the New Yorker

Paul Muldoon in the New Yorker

Rae Armantrout in the New York Times

David Orr in the New York Times

Tania Kentenjian in the Guardian

John Emil Vincent at the Best American Poetry blog

Terence Winch at the Best American Poetry blog

Evan Kindley in the New Republic

David Lehman in the American Scholar

Christian Lorentzen at Vulture / New York Magazine

Crossposted with Locus Solus: The New York School of Poets

About the Author:

Andrew Epstein is a Professor in the English Department at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida, where he is also currently the Associate Chair for Graduate Studies. He is the author of Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry (Oxford University Press), which focuses on Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and Amiri Baraka. His most recent book, Attention Equals Life: The Pursuit of the Everyday in Contemporary Poetry and Culture was published in 2016 by Oxford University Press.