Notes Towards a Deranged Realism

Black Mirror, Endemol UK

by James Miller

The trouble with fiction is that it makes too much sense. Reality never makes sense.

—Aldous Huxley

Before the confusion sets in, I’m going to try to make some statements, set out a few positions that will also be provocations and, inevitably, generalisations. First, all art is political, particularly the novel and novels both reflect and respond to the political conditions that surround and – to a certain extent – determine its production.

Second, late capitalist Anglo-American society is going through a period of protracted crisis and decline. No one, neither the politicians nor the artists (and certainly not the people) can envisage a credible future; we prefer to ignore the iceberg and arrange the deck chairs. The combined effects of recession and the subsequent austerity; rapid social change and generational conflict; regional instability leading to mass migration; terrorism and religious extremism; stagnated wages, the bonfire of benefits (capitalism unleashed, red in tooth and claw); technological innovation coupled with looming ecological catastrophe, it’s all here: these factors reverberating throughout the body politic. Contaminating. Dark forces emerge from the social id: all the separatisms and nationalisms, racisms, sexisms, the backward-isms and irrational fantasy-isms blooming like noxious weeds only now our politicians and media cultivate them, toxic gardeners watering the flowers of our destruction.

Third, although these crises appear new in an Anglo-American context they have been commonplace throughout the non-western and post-communist world. Indeed, I would argue that the Anglo-American world has merely caught up with these other crises, that rather than being ‘ahead’ we were ‘behind’ (or, if it doesn’t strain the metaphor too much), that these crises have ‘blown-back’ onto us (to cite Sartre commenting on Fanon).

Fourth, I want to suggest that these crises, exacerbated by a collapse in traditional nodes of authority and a proliferation of competing affective signals – particularly the manipulation of social media and fake news – have in turn created a crisis in the notion of the real or reality, a schism that accelerates further derangements in our society, politics and culture. And, finally, that we have yet to see how these derangements will express themselves in terms of narrative fiction but that the clues to the future of the Anglo-American model (exceptional no longer) may perhaps best be found in the innovations and experimentations of Third World, post-communist and European literature, traced by the past avant-gardes of modernism, magical realism, surrealism, anything that troubles realism as a stable category and has no illusions about the coherence or credibility of the field through which it moves.

The future is broken, progress has stalled: both left and right wallow in regressive and nostalgic fantasies of national renewal, promising to “Make America Great Again” and “Take Back Control” but everyone knows these words are hollow. We watch the high-divers, prancing and preening as they get ready to jump – but the pool is dry, there is no water, nothing to cushion the fall. We’re all waiting for the jump, a moment of showy, bravura display, then the fall, the messy impact. The shattering of the final illusion.

Okay. Deep breath.

You see, the thing is I find myself thinking a lot – in my writing, my teaching and in ‘real life’ itself – about “reality” and “realism.” What is it that we understand by these concepts and how do they relate to language, narrative structure and story. Or is it language, structure and story that shape this thing we call the real, that enable us to see it, grasp it, understand it? I’ve always been suspicious of reality, the way in which things ‘seem’ to be and how we then represent this semblance. There has never been a direct, unproblematic relationship between words and things but always a complication, a mediation, a troubling. I’m also concerned about how far certain concepts that we tend to take for granted when reading a novel (story structure, the tropes of genre, the assumption of a correspondence between the world of the story and the world in which we find ourselves) – are influenced by political, social, economic and technological forces and again how the writer – or, that is to say, the engaged writer – is meant to respond.

Wait. Let me take a moment. Something has just come up on my Twitter feed.

Well… that’s worrying, isn’t it? “Appropriately respecting.” What does that mean? Hmm…

Anyway. Where was I?

Right, yes, realism, ‘reality,’ the real. They’re not the same, of course. But realism, as a literary-artistic mode has persisted for a good three hundred years – ever since the inception of the novel (I’m thinking Austen and Defoe, definitely not Swift or Sterne) – and continues to flourish today. Although realism as a movement in literature had its heyday in the nineteen and early twentieth century, if we peruse the new fiction table in any bookshop then the majority of titles, including (especially) so called ‘genre fiction’ can also be understood as works of realism (even if their characters and the events they depict are not ‘realistic’). That is to say – these books propose a coherence and a degree of transparency between words and the world: words relate to the world and make it intelligible; these novels try not to draw undue attention to the language with which they express things (as if words are a transparency forming an unambiguous screen of apprehension); furthermore, things are knowable, we have characters with ‘characteristics’ and there are structures or plots that map the things that happen to the characters into meaningful events. There is such a thing as narrative time and narrative time tends to move forward. There is a chronology, there is cause and effect. There is progress. There are secrets but secrets will be made legible and resolved by the story.

In this sense, fiction and the writing of history, biography and memoir share a correspondence: they turn the chaos and randomness of life into a narrative, which means life (reality, the real) is subject to structures of plotting and representation drawn from fiction. As the philosopher Paul Ricoeur notes, this process makes life legible: “do we not consider human lives to be more readable when they have been interpreted in terms of the stories people tell about them… literary narratives and life histories, far from being exclusive, are complementary.” If anyone asks, how did you meet your wife? Well, you will answer by telling them a story…

But we also know ‘the real’ of reality and the real of realism are far from the same. The world we think we see, the world as it appears to us and the world as it actually is are very different. It depends how we look at things. A question of perspective, perspectives that are inflected by technology, by science but also by class, age, race, gender and location (or situation). To take that the idea quite literally: right now, I appear to be sitting here, at a table that seems both solid and separate from me. But quantum physics shows us this is not true. My perception of reality is wrong. Neither me nor the table are as solid or as distinct as we think. Mathematics and scientific observations, operating with a precision unimaginable in discourse, show that our particles are interacting in a single vibrating field of energy. Nothing is remotely as it seems.

Wait. What’s this?

“Infiltrated.” “Propaganda machine.” Fucking hell. What is this bullshit? I hate that shithead, I really do, this fraud who claims to be a ‘patriot’ while secretly working for Putin, talking about “the will of the people” when it’s an ideal rooted in European revolutionary movements, totally alien to the traditions of British Parliamentary democracy. Not that anyone in power seems to know this. Christ alive.

Where was I?

No, the thing is, for a long time now I’ve felt that we’ve been experiencing what I call a “reality crisis.” It seems to me that reality, which is to say, the visible world as constituted and mediated by signs, has become deranged, has broken free from consistency, reason and a certain circle of acceptability and continuity that previously defined so much of both Anglo-American culture and Anglo-American politics.

On the one hand, this is nothing new. Back in the ’90s – when we thought the contradictions of the past were resolving themselves and world historical progress towards a liberal-capitalist quasi utopia actually seemed like a viable thing – numerous theorists pointed out that the arbitrary relationship between signs and the things they signified had flipped: signs now structured the world and the shape of reality was dictated by the media image of itself. I remember reading my Baudrillard, Jameson, Lytord and others, stoned in my room in Oxford (busy attempting my own Rimbaudian derangement) and thinking “oh, this sounds cool, wow.’ But then we still thought the Anglo-American world was at the forefront of progress, that the dialectic of history was working through us, that we were the future. We protested Starbucks because we thought the Nazis were long gone. Happy dreams…

No, the truth is this thing – if we can call it a thing (a trend, a tendency, a turn?) has been going on for a long time now. The rest of the world has suffered this derangement, this dislocation, this abandonment of the acceptable, this inversion of values, the flip and crumble of history, the sense that society is vulnerable, bound by force and fear as much as the bonds of common interest and shared experience. Western Europe has suffered it – dictatorship, war and occupation – and remembers and is trying to learn from the experience. The difference is now the Anglo-American world – which always thought of itself as exceptional, as not the same and not to be judged by the standards that apply to the rest – is having its turn. The grim nadir of Trump and Brexit, a process accelerated and manipulated by mass media, social media, foreign agencies, dubious billionaires and shadowy research companies. Our own reality is also, it turns out, a construct, an ideology, a function of power. And so malleable, so easily manipulated.

Wait a minute…

He’s not supposed to say that, is he?

I mean… this just can’t end well.

In other words, how might the concept of ‘combined and uneven development’ be applied to the novel and to literary modes as a reflection of socio-economic and political distortions? Or, in other words, perhaps predominantly realist writers such as Ian McEwan or Rachel Cusk, whose novels explores the interior conflicts of bourgeois individuals under late capitalism, are better understood as primitive writers inhabiting a calcified zone of perception as yet (relatively) uncontaminated by the derangements of our present crisis whereas – by way of contrast – in the work of writers such as Aime Cesaire or Luisa Valenzuela we might better glimpse the possible futures for Anglo-American fiction.

The coherence of the Anglo-American mode of realism in fiction is a comforting nostalgia, a memento of our fading supremacy.

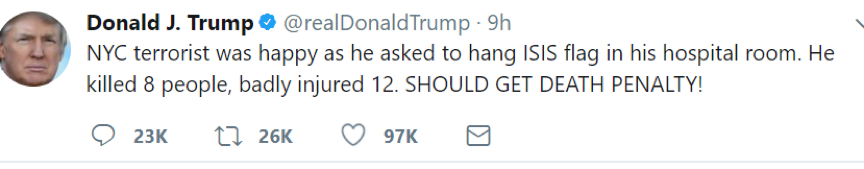

I mean, look at this:

It’s all here: the sense of an endless conspiracy, the deployment of social media to create false narratives that become true, the engagement and promotion of absurd notions (Texas succession, the Islamification of Texas) out of media signs; a blurring of the distinction between an event that was staged and an event that was real in a way that makes Tom McCarthy’s ‘Remainder’ seem quite tame (ie the protestors are, one assumes, not Russian agents but genuine Texan suckers). There is, surely, a novel’s worth of material in this tweet alone – and how does the commentator attempt to account for what happened, but with reference to genre fiction and pop culture (‘The Twilight Zone’) as they give a better explanation or accounting ‘of what really happened’ than any historical examples.

I propose that the engaged writer of today responds to such a reality with what I call deranged realism, a Janus-faced fiction of beginnings and transitions, one that attempts to partake in and disengage from the maelstrom of the present moment. A radically subjective fiction, where narrators can only be unreliable, usually disreputable and almost always first person voices, immersive and obscene, inhabiting the present tense, expressive of particularities and vernaculars and – like everyone in ‘the real’ – continuously distracted, addicted to gadgets, to social media, substances and popular culture: bizarre tapestries of appetite rather than a formal coherence of character; anti-heroic, only sporadically epiphanic, unlikely to find closure or redemption but also to be depicted (in a nod to the ‘objective truths’ of literary realism) shitting, fucking, wanking, day-dreaming, trolling, lusting and doing nothing. Works of deranged realism are works of anti-art, anti-fiction, texts that acknowledge the belated status of ‘art’ in an age of accelerated collapse. As Lars Iyer wrote, we “dream of literature” while skimming the Wikipedia page about ‘the Novel’ and watching cat and dog videos on our phone. We grasp, in such moments, that there’s no such thing as being ‘original’ anymore, the old macho Modernist yearning for the true word and the authentic style went long ago. What we have is a matter of reorganising pre-existing tropes, types and structures. It is the reorganisation itself that matters, whether the reorganisation is ‘knowing’ or ‘unconscious,’ whether it flaunts or suppresses itself. Transgressive texts, ‘queer’ texts that merge boundaries and blur distinctions, texts that plunder genre fiction because reality itself has become (or is trying to become) genre fiction. Sick fiction for a sick age. Media fiction that subverts, highlights, even celebrates the fact that this an age that styles itself after media images. Fiction that recognises the supremacy of the Anglo-American world is over. Funeral orations for our decline: sad, funny, disgusting, cathartic. Everything a dark satire because the President is a pervert and an imbecile and Anglo-American progress means racist trolls posting Nazi propaganda on Twitter while jerking off to porn.

Wait a minute… what’s this? What now?

About the Author:

James Miller is a novelist and academic. His debut novel Lost Boys (Little, Brown) was published in 2008 and his second Sunshine State (Abacus) was published in 2010. UnAmerican Activities, James’ third novel, was published by Dodo Ink in 2017.