AWP Diary

by Joe linker

March 24, 2019

The annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) convention is being held this coming week in my home town of Portland, Oregon. I’ll try to post daily through the week my local observations of the main event and its various outlier happenings. One of those happenings is the concurrent publication of Berfrois the Book and Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book (Dostoyevsky Wannabe Original, 2019). Editor at large Russell Bennetts will be on hand at the AWP Berfrois table with an ample supply hot off the press.

These two anthologies of contemporary writing include work by a community of writers from around the world whose collective voice argues for independent and alternative, experimental, grass roots writing and engagement in the Humanities. By calling them a community, I don’t mean to suggest I personally know any of them. I don’t. Nor am I deeply familiar with the writing of them all. I have, however, since my own discovery of Berfrois about ten years ago, and later when Queen Mob’s Teahouse went online, followed the progress of several writers appearing there, and remain a frequent reader of the sites. And of the whole I’m confident in calling it not only international but diverse in all the characteristics generally acknowledged to matter in today’s world, at least to those whose hearts beat in their chests and not in their pockets. Which is to say the community seems genuinely united in standing for freedom from tyranny or abuse of any kind in any place.

There of course we swim into deep waters, for the books, designed and published by the neophyte press Dostoyevsky Wannabe, are printed via the gargantuan Amazon. The DW press readily speaks to the issue which for some could be a show stopper – from their About page FAQ:

“Where d’you stand on the ethics of using Amazon?

We stand where every radical bookshop and arts organisation and alternative and independent organisation stand when they use Twitter and/or Facebook, or when they use a smartphone or a laptop made by another similarly faceless corporate entity who may or may not be very ethical. Ask any giant faceless corporation how ethical they are (ask their lobbyists). We stand where zine makers stand when they use Hewlett Packard or Canon printers or photocopiers. We sometimes also sit in cars and on buses that pollute the earth much the same as other independent and radical and alternative organisations. We don’t like that we have to more or less do this but we do.

Or as one of our good friends put it recently: ‘I hear Richard Kern used Kodak film for his movies. Was he really No Wave?’”

I mention the publishing platform question here in anticipation of possible staid literary critical rebuttal to the content. When Ferlinghetti began City Lights, back in the 50’s, he wanted to establish a literary community, and he did so on the back of paperbacks, at the time a sign of inferior publishing content. In any case, literary revolution was ever so, as a review of the so-called modernist journals will reveal. The work is radical at least in as much as it questions the status quo of form, content, gatekeeping (including academic), and distribution. The Berfrois and QMT work also seems inspired at least in part by the open source, open access, creative commons, and dropping paywall movements (particularly where academic or research papers, already in part publicly funded in many cases, are concerned). The work is Indie and Alternative, and departs from traditional industry publication methods much as the work of musicians has ventured away from the traditional recording industry – all enabled of course at least in part by technology but also perhaps by a general turning away from or shrugging of the shoulder at the popular, the mall-ed, the commercialized, but as well from the so-called credible, reliable, cited sourced and footnoted, peer reviewed. There’s a new pier in town, and it’s not Stephen’s disappointed bridge. It at least points toward something new.

Not to say though any one individual within the Berfrois and QMT community has not also benefited from or would refuse professional (i.e. paying) gigs. I almost framed for the wall my poem accepted and published in The Christian Science Monitor back in 2009, for which I was paid the handsome sum of $40.00. I was going to frame a cutout of the poem with the check, but I ended up cashing it to help fund my book habit. There are of course differences between writing for payment (at least one of the prerequisites to the ranks of pro) and writing for payment enough to quit one’s day job. Or night job. Or multiple jobs. Add to that one’s status as an adjunct of any organization and we wonder what kind of fuel keeps these engines running when they can only run in overtime mode. But nor is this work simply about “exposure” in lieu of pay or some sort of deferred payment or contract. Maybe, at its core, it is about the amateur spirit in writing, a spirit we remain loath to lose, as E. B. White suggested, no matter how professional we become.

So who are these spirits whose light has filled our screens and now illuminates the pages of the Book and teh Book? They do indeed include both professionals and amateurs by imprimatur and in their own right. As with any group of artists, bohemians, intellectuals, their diversity skews any leaning toward a unifying code that might undermine their independence. To what degree is calling these Berfrois or Queen Mob’s writers a community even accurate? Has someone proclaimed a movement, written a manifesto? Do they form a new school of writing, such as the Imagists, or later, the Beats? To call these writers a community might be simply to identify the line of best fit. “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” as Dorothy says upon landing somewhere over the rainbow. Or maybe that’s exactly where we are, Kansas. But what exactly is an artist and where do they work and reside? Recall father and son from Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”:

“There’s that son of mine there not half my age and I’m a better man than he is any day of the week.

—Draw it mild now, Dedalus. I think it’s time for you to take a back seat, said the gentleman who had spoken before.

—No, by God! asserted Mr Dedalus. I’ll sing a tenor song against him or I’ll vault a five-barred gate against him or I’ll run with him after the hounds across the country as I did thirty years ago along with the Kerry Boy and the best man for it.

—But he’ll beat you here, said the little old man, tapping his forehead and raising his glass to drain it.

—Well, I hope he’ll be as good a man as his father. That’s all I can say, said Mr Dedalus.

—If he is, he’ll do, said the little old man.

—And thanks be to God, Johnny, said Mr Dedalus, that we lived so long and did so little harm.

—But did so much good, Simon, said the little old man gravely. Thanks be to God we lived so long and did so much good.

Stephen watched the three glasses being raised from the counter as his father and his two cronies drank to the memory of their past. An abyss of fortune or of temperament sundered him from them. His mind seemed older than theirs: it shone coldly on their strifes and happiness and regrets like a moon upon a younger earth. No life or youth stirred in him as it had stirred in them. He had known neither the pleasure of companionship with others nor the vigour of rude male health nor filial piety. Nothing stirred within his soul but a cold and cruel and loveless lust. His childhood was dead or lost and with it his soul capable of simple joys and he was drifting amid life like the barren shell of the moon.”

Perhaps, then, there is some kind of temperament that brings and holds the Berfrois and Queen Mob’s writers together. Throughout the writing, one begins to recognize the use of certain scales. And when you mix them together you get the four body humors. And more, and there’s the humor of it. The temperament might, after all, belong to Russell Bennetts. I wonder if Russell wouldn’t prefer pizza and a beer with the hearty senior Dedalus rather than the morose Stephen. But that sets up an out of whack either or fallacy, and anyway, Russell has already invited them both.

Berfrois: The Book includes work by 41 writers. Queen Mob’s Teahouse: teh Book includes work by 57 writers. Only two writers appear in both, so 96 writers from around the world represented. Many are US or UK, some Canada. New Zealand. Tokyo. Singapore. Berlin. Melbourne. Chile. Paris. Netherlands. India. Poland. That much a reader can see from the short biographies included at the end of each book, many of which though don’t name a place. In any case, Joyce said he could write anywhere. Hemingway said he could too, but maybe he wasn’t so good in some places. Where one might be located at any given moment does not necessarily betray one’s identity as a writer. For that, we must read beyond the biographies to the work. Writers travel outside time and place and person, even if they never leave their desk. As do readers.

I’ll be reading through the anthologies this week and commenting on the writing and the conference as the week wears on. I’m hoping to meet up with, in person, the, as Jeremy Fernando would say, inimitable Russell Bennetts, who is apparently already in Portland town for the conference. I already missed an opportunity yesterday.

March 25th, 2019

One day, almost ten years ago, down at the Bipartisan Café, in Montavilla, reading on my laptop, I was gobsmacked to find someone had published on their site a piece I’d recently written for my blog, The Coming of the Toads. At the time, I’d not yet heard of Berfrois or its editor Russell Bennetts. Now, with book publications Berfrois the Book and Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book (Dostoyevsky Wannabe Original, 2019), Berfrois opens a new wing in its reach for readers and writers.

This week, the annual Associated Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) conference is being held here in Portland. Berfrois will have a table in the book fair, the new books available for perusal, purchase, on display.

Ten years is already a long life for an enterprise devoted to and sustaining a “literary-intellectual online magazine” – that updates daily, no less. And Berfrois has managed to remain ad free while adding writers and readers, expanding its original format and content, publishing in addition to poetry, fiction, essays, photography, and notes and comment from around the Web, books in Ebook format: Relentless’ by Jeff Bezos, and Poets for Corbyn, for example.

Yet those same ten years have seen the continued growth of “the reading crisis,” and the “death of blogs,” debate over online versus paper reading, argument over possible decline in reading abilities and skills, and the perceived watering down of the value of a Humanities degree. Higher education is, in the opinion of many, in turmoil as increasingly news appears of schools turning to business models, cutting traditional programs, and even turning to sketchy recruiting schemes as revealed in the recent college admission crisis story, and all the while tuitions and fees rising while the whole edifice relying more and more on an adjunct workforce unable to sustain itself on local economies. What’s a writer to do?

You might move to New York, or get an MFA. That’s a choice? Or do both? Elizabeth Bishop did, sort of. She moved to New York and began teaching in a program, the “U.S.A. School of Writing.” It was a correspondence course, the kind that used to advertise on the back of a book of matches. Having just graduated college, Bishop was in New York during the Great Depression:

“Perhaps there seemed to be something virtuous in working for much less a year than our educations had been costing our families….” [but] “It was here, in this noisome place, in spite of all I had read and been taught and thought I knew about it [writing] before, that the mysterious, awful power of writing first dawned on me. Or, since ‘writing’ means so many different things, the power of the printed word, or even that capitalized Word whose significance had previously escaped me and then made itself suddenly, if sporadically, plain….”

What Bishop is talking about is “Loneliness.”

“In the case of my students, their need was not to ward off society but to get into it…Without exception, the letters I received were from people suffering from terrible loneliness in all its better-known forms, and in some I had never even dreamed of.”

(The New Yorker, July 18, 1983, retrieved 25Mar19 via TNY on-line archive available to subscribers).

With a few small changes, Bishop’s article might have been written by an adjunct instructor in today’s education marketplace. It seems unlikely though that the attendees I’ll see around AWP19 will all be lonely. But how’s a mere reader to know?

March 26th, 2019

Writing grants access. To what? First, to one’s own thoughts, to one’s own experience. I wrote this; therefore, it happened to me, at least the writing of it did. So I have access to that, to the writing, another experience of the experience, another way to experience the experience. Are you experienced? Narrative becomes mirror, but like mirrors in a carnival funhouse. Writing is a ticket into that funhouse.

Can anyone write? Does anyone want to? In what has by now become a classic article that appeared in the May 26, 2008 New Yorker, Ian Frazier reflects on the years he spent volunteering at a soup kitchen, offering a writing workshop:

“Almost everybody who talked to me said they had some amazing stories to tell if they could only write them down. Many said that if their lives were made into books the books would be best-sellers. Some few had written books about their lives already, and they produced the manuscripts from among their belongings to show me. If you take any twelve hundred New Yorkers, naturally you’ll find a certain number of good musicians, skilled carpenters, gifted athletes, and so on; you’ll also come up with a small percentage who can really write. Lots of people I talked to said they were interested in the workshop; a much smaller number actually showed up. Some attended only one session, some came back year after year. In all, over fourteen years, maybe four hundred soup-kitchen guests have participated.”

We could all of course at least tell of our teeth. Stephen did, wandering wondering what he did:

“He took the hilt of his ashplant, lunging with it softly, dallying still. Yes, evening will find itself in me, without me. All days make their end. By the way next when is it Tuesday will be the longest day. Of all the glad new year, mother, the rum tum tiddledy tum. Lawn Tennyson, gentleman poet. GIA. For the old hag with the yellow teeth. And Monsieur Drumont, gentleman journalist. GIA. My teeth are very bad. Why, I wonder. Feel. That one is going too. Shells. Ought I go to a dentist, I wonder, with that money? That one. This. Toothless Kinch, the superman. Why is that, I wonder, or does it mean something perhaps?”

Today is Tuesday, and AWP19 setup begins tomorrow. We’ve to move the “heavy” boxes of Berfrois: The Book and Queen Mob’s Teahouse: teh Book from distribution depot closer to the Oregon Convention Center to coordinate the retail flow that will surely follow Thursday with setup complete and the Bookfair opens. The rain has let up today. The sun is out, the sky blue. Good weather for moving books. Don’t have that problem on line. Move books anywhere, anytime, instantly. Nice to have something physical to do though, lay the hands on. Honest labor. Meanwhile the travels and travails of today’s Portlanders continues, as one generation slows down and another honks its horn, stuck in traffic.

What is Portland famous for? A question I was asked yesterday. Vanport. Jazz. Homelessness. The Attic Institute: A Haven for Writers. Street Potholes. Neighborhoods, sitting out, libraries. Coffee houses, pubs. Powell’s Books. Dentists? Not so much. Marijuana dispensaries:

“The chemist turned back page after page. Sandy shrivelled smell he seems to have. Shrunken skull. And old. Quest for the philosopher’s stone. The alchemists. Drugs age you after mental excitement. Lethargy then. Why? Reaction. A lifetime in a night. Gradually changes your character. Living all the day among herbs, ointments, disinfectants. All his alabaster lilypots. Mortar and pestle. Aq. Dist. Fol. Laur. Te Virid. Smell almost cure you like the dentist’s doorbell. Doctor Whack. He ought to physic himself a bit. Electuary or emulsion. The first fellow that picked an herb to cure himself had a bit of pluck. Simples. Want to be careful. Enough stuff here to chloroform you. Test: turns blue litmus paper red. Chloroform. Overdose of laudanum. Sleeping draughts. Lovephiltres. Paragoric poppysyrup bad for cough. Clogs the pores or the phlegm. Poisons the only cures. Remedy where you least expect it. Clever of nature.”

Writes in his head, does Bloom. Blooming thoughts. Should have been a writer. Too cryptic. Where does the intellectual meet the body? In the mouth:

STEPHEN: See? Moves to one great goal. I am twentytwo. Sixteen years ago he was twentytwo too. Sixteen years ago I twentytwo tumbled. Twentytwo years ago he sixteen fell off his hobbyhorse. (HE WINCES) Hurt my hand somewhere. Must see a dentist. Money?

March 27th, 2019

The 19th annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs convention (AWP19) coincides with the 10th anniversary of the online site Berfrois, celebrated these last ten years for its “Literature, Ideas, and Tea.” Berfrois will be at the AWP convention with copies of its recently published books.

The two hard copy books are anthologies. They include writing by various writers that have written for either Berfrois or Queen Mob’s over the years and more. But the writing in these book print anthologies is new, entirely original, previously unpublished in any form. The writing has not been seen online, nor will it be (except of course for quoted material in reviews, etc.). The books represent a new effort by Berfrois editor Russell Bennetts to engage print, a formidable challenge in this age of Ewriting and Ereading in an Eworld.

March 28th, 2019

Nevermind, I’m already 10 minutes late for my appointed volunteer shift at the Portland Convention Center to help out at AWP19. Turns out even 11:30 am too early for this old kid to gig. I hope my unexcused absence doesn’t reflect too poorly on my literary reputaughtshun. But I will use the time though, looking ever closer and deeper into Berfrois: The Book and Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book.

Whenever confronted with conventions, I remember the Salinger story “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” which begins:

“THERE WERE ninety-seven New York advertising men in the hotel, and, the way they were monopolizing the long-distance lines, the girl in 507 had to wait from noon till almost two-thirty to get her call through. She used the time, though. She read an article in a women’s pocket-size magazine, called “Sex Is Fun-or Hell.” She washed her comb and brush. She took the spot out of the skirt of her beige suit. She moved the button on her Saks blouse. She tweezed out two freshly surfaced hairs in her mole. When the operator finally rang her room, she was sitting on the window seat and had almost finished putting lacquer on the nails of her left hand.”

Why ninety-seven? The 97th Infantry Division was active in WWII, but Salinger served in the 4th Infantry Division. In any case, today, “the girl in 507” would, in addition to all her other time using activities, be on her cell phone, wouldn’t she? As for the advertising men, they might be attending an Associated Writers and Writing Programs annual convention, such as AWP19, this week being held in Portland. Portland is a good place for bananafish. Maybe something to do with all the rain. In the today Salinger story version, AWP might be an acronym for All Earwickers Post.

But the word “ear” appears only once in Berfrois: The Book. Six times in Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book. One can read too closely. And that’s just whole words, anyway. Backing up a bit, we see “ear” appears frequently as part of other words: years, bear, Radishes, breath, Misrepresentation (in the Berfrois book); Eavesdropping, great, Picaresque, artes, Funeral, Breakfast (in the Queen Mob’s book).

The only use of the whole word “ear” found in Berfrois the Book is in the essay by Ed Simon, “Moved the Universe: Notes Toward an Orphic Criticism” (59:72):

“…Erato whispering in Sappho’s ear…” (59).

In his essay, Simon speaks to the mystery of literature. It’s what can’t be quizzed in class. Nor is it:

“I’ve no interest in taste, discernment, or style…” (66).

Simon is talking about the ear, about listening. He’s not asking what is literature, but where does it come from, and how does it get here. How do we hear it, learn it, learn to listen to it, for it. It’s a raw approach. It cuts through a lot of crap:

“What defines the Orphic approach is never necessarily analytical acumen (certainly not that), nor adept close readings, but rather, an ecstatic, enchanted, enraptured sense of the numinous at literature’s core. Orphic criticism is neither method nor approach, but rather attitude and perspective” (71).

For a reader, the attitude might have a bearing on Nabokov’s emphasis on relying on one’s “spine,” the “tingle” that goes up it when the magic kicks in:

“A major writer combines these three – storyteller, teacher, enchanter – but it is the enchanter in him that predominates and makes him a major writer…a great writer is always a great enchanter, and it is here that we come to the really exciting part when we try to grasp the individual magic…In order to bask in that magic a wise reader reads the book of genius not with his heart, not so much with his brain, but with his spine. It is there that occurs the telltale tingle” (5:6). (Nabokov, “Good Readers and Good Writers,” from “Lectures on Literature,” Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1980).

Simon’s essay is in form a classic argument, and a perfect example of one. Plus, we get a history of literary criticism and enough references to keep us going for some time. The essay bemoans the very academic sustenance that gave it life, but explains why. In essence, theory grows monstrous when it becomes horror to the common reader. Simon’s statement, about which there will be some disagreement, I found very persuasive, intuitive, purposeful, clear and concise yet thorough and clarion in its call to let the sound back into the word.

Justin Erik Halldor Smith‘s “The G.O.E” (101:108 B:TB) is, at least in one sense, also about the ear:

“What I remember most vividly is the great cleavage, in the earliest time, when the moon was torn away from us” (101).

The speaker seems to be an ecological griot, an evolutionary being that “remembers everything,” and attempts to dialog with those who may have forgotten or never knew:

“There is a memory that runs through all of us unbidden, and that can be brought to the surface with a little effort. In this effort, we stop being I and thou, which seems implausible, but I have always felt that coming to see oneself as an I in the first place was the far more remarkable way of apprehending the world, while conjuring our shared memory with all the other Is is by far less remarkable” (101).

Justin’s piece is in form a parable. Why is life so reliant on symbiotic relationships that eat one another? There is a partnership, on Earth, at least, of animal and plant life. At least one form from the animal life world has suppressed and oppressed plant life. Too, within the animal world, there are unmarked distinctions that have grown into borders creating divides that threaten all kinds of partnership. Why does life eat itself so?

We find more “ears” embedded in “Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book.” But, before we get too far away from “the girl in 507,” we find, in QM’sT:tB, “advertising.” Only once, both books combined, do we find the word “advertising.” It’s in “Conductor,” by Nate Lippens:

“I drive around my hometown, past the Sons of Norway advertising a Saturday lutefisk lunch, past the strip mall, past the mega-stores and past the Irish sports pub where men who look like fraternal twins line the bar with boilermakers” (187).

How is disgust drawn, when even one’s mother expresses doubt? While pure hate simply ignores, or pretends to. What happens when dislike pierces the skin so often we begin not to like ourselves, and begin to scratch away at an itch the source of which we know comes from where? Do we begin to blame ourselves for being the lightning rod? Nate’s piece seems a personal essay (it could be a story, the narrator a character). The writing is visceral, honest, seemingly true to experience. The writing is clear, drives forward without blinking. The essay contains the kind of writing you feel in your spine.

We interrupt this post for a PSA (Public Service Announcement): I’ve learned that I am being given the opportunity of redeeming myself from today’s (now, as I continue these notes, yesterday’s) unexcused absence. Either tomorrow or Friday, This afternoon, I should be helping out at the Berfrois table at AWP19 for a spell. I’ll be wearing my ears and my advertising cap. If your there, the table ID is T11094. We might talk about how I’ve no doubt misread Simon and Smith, Lippens, and now Pickens?.

Meantime, in the Queen Mob’s book, we find Robyn Maree Pickens using the word “ear” in “The skeleton of a dog who is still alive” (47:57).

“She has been trained to fix her gaze on the clients’ hairlines or ear tips” (48).

The story moves in a form of dream language, which is to say surreal, both clear and unclear at once. Yet,

“Her dreams are full of bounding for terriers. They are either benign guides or soporific constellations that suffocate her eyes. They must never talk about dreams at the institute. She registers the cessation of oscillating air on her head and leaves the circle” (51).

Perhaps the secret to reading all dreams is simply this:

“All references are lost. Their lives are so short. They glisten. They hum” (57).

The Pickens story also is the kind that you feel in your spine.

This is the fifth in a series with notes on AWP19 and the concurrent publication of the Berfrois and QMT books. I’m reading through the Berfrois anthologies this week and commenting on the writing and the conference as the week wears on.

March 29th, 2019

I arrived a bit early for my scheduled stint to help out at the Berfrois table at AWP19, so I wandered through a few aisles of tables set up for the book fair. At each table, a couple of usually amiable greeters happily and professionally described the occasion or purpose of their press or otherwise writing or teaching venture. The number of tables was daunting. If 6 was 9 there wouldn’t be time to peruse them all. In the lobby, the wait in the long, long line reminded me of the line for a ride at an amusement park, a long stretch of individuals lined out through the main rotunda, waiting to enter the ticket area, where the line then snaked through numerous switchback turnstile aisles. My friend Bill, who had arrived early, said he’d waited in line for two hours. He voiced his complaint to us at the Berfrois table. As T. S. Eliot might have said, had he not been so gloomy, “I had not thought spring had undone so many.” The sun was out in Portland town. The only way to proceed was at random, psychogeographically. The book fair of course is only one event at any AWP. I enjoyed my short wander, but it was a bit like shopping, which I don’t much care for. Life is subject to change.

One of my favorite stops in the book fair was at the table for the Otis College of Art and Design. The college, its main campus in Westchester, is 100 years old, and is located about a mile from where I attended high school, in Playa del Rey, an unnotable fact I shared with Kyle Fitzpatrick, who I visited with for some time, discussing his school, the books exhibited at his table, and what’s happening in Los Angeles these days.

I purchased several of their books: “Seeing Los Angeles: A Different Look at A Different City,” edited by Guy Bennett and Beatrice Mousli; “Swell,” by Noah Ross; and “Proof of Loss,” by Sara Marchant. What sold me on the “Seeing Los Angeles” book was a photo by John Humble, from Shooting L. A., titled “343 Hillcrest Street, El Segundo, May 13, 1995.” My father moved his family to El Segundo the same year the Brooklyn Dodgers announced its move to Los Angeles: 1957. The first house we lived in was at the time one of the oldest in El Segundo, a rental house, an old unpainted wood shingled house, and was located on Hillcrest. It’s of course now long gone, and was located farther north on Hillcrest than the one in the Humble photo. Talking with Kyle, I was reminded of Reyner Banham’s “Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies,” now back in print. But I couldn’t recall the title accurately, so there you have it.

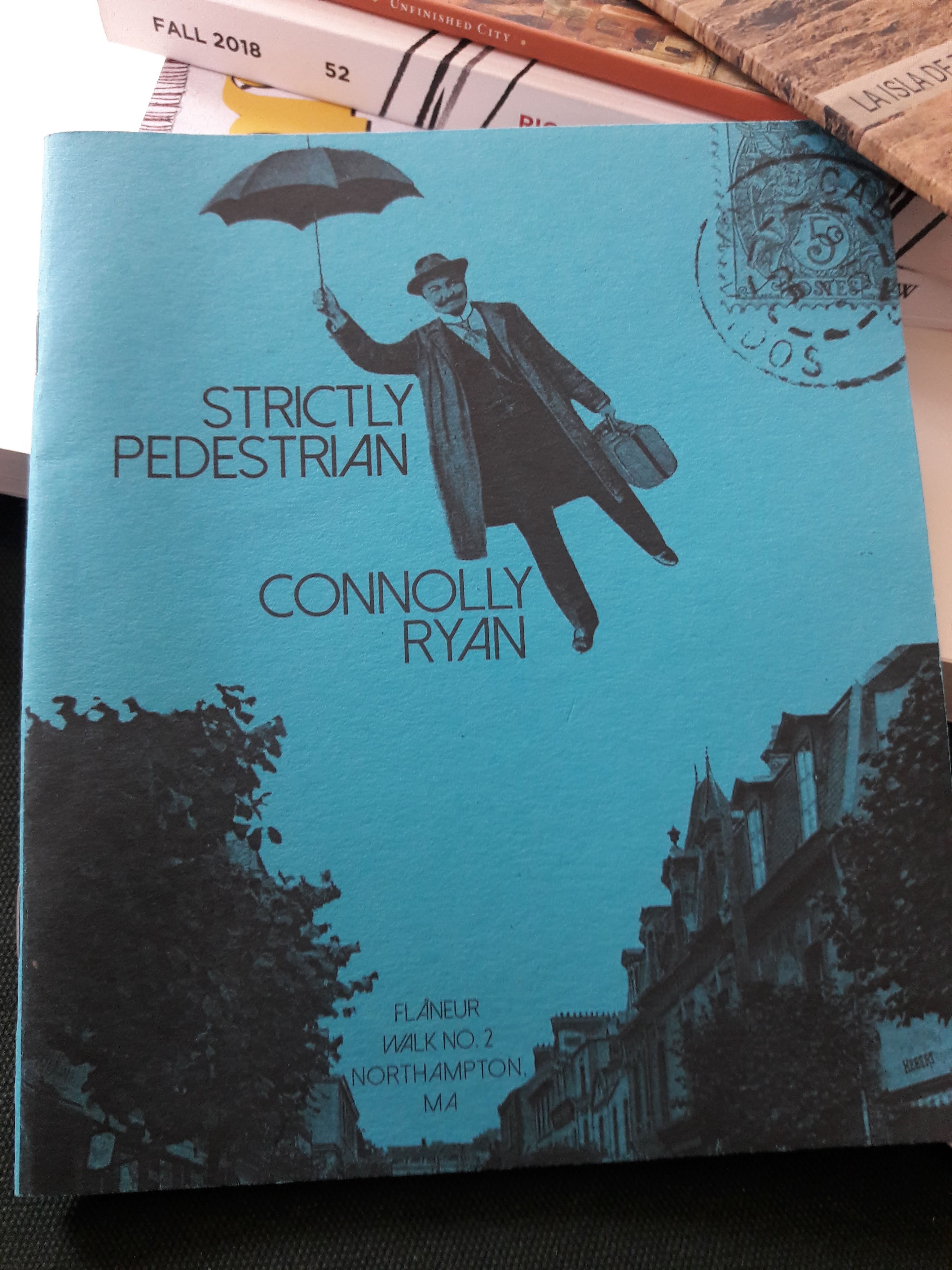

I met Maria Williams-Russell, editor in the Flaneur Walks Pamphlet Series, put out by Shape Nature Press. By now, of course, I had my meme of the day, and could not leave Maria’s table without buying a copy of “Strictly Pedestrian,” by Connolly Ryan. The book begins:

“Like all great walks, this one begins in a park.”

I asked Maria to sign the page with her “Editor’s Note,” and she did, but I could tell she thought the signing a bit silly since she wasn’t the author, and I continued my saunter.

Back in 1969, I found myself miserably in the Army at Fort Bliss, Texas, which is in El Paso. So I stopped at Veliz Books, sharing space with the Rio Grande Review, of the University of Texas at El Paso. From Veliz, I purchased a copy of “La Ilsa De Tu Nombre,” by Gabriela Aguirre. I talked with co-founding editor and publisher of Veliz, Minerva Laveaga Luna. I mentioned my time in El Paso, and talked some about my time at Portland Community College teaching ESL and ENNL in the late 70’s and early 80’s. There was a professor of the bilingual MFA program at the UTEP sharing the booth – unfortunately, I neglected to note his name, and I can’t recall it. He was a good listener, and encouraged me to continue learning Spanish, which I’ve not studied seriously since high school. And they shared with me their hopes for their work, students, and writers.

Meanwhile, back at the Berfrois table, editor Russell Bennetts was busy explaining his hopes for his own work and writers. He was able to say hello to a few writers he’d not met in person before, including Robin Richardson, whose one page piece in Berfrois: The Book, titled “Stockholm Syndrome,” is a block paragraph with no punctuation marks:

“It was the face it was the width the weight of it” (195)

March 30th, 2019

They look like anyone, these poets and writers, intellectuals and artists, editors and publishers – filling and milling about the Oregon Convention Center for AWP19, sauntering though the book fair and scurrying off to panels and readings and private receptions. The fact of a book must say something about their ability to write, to argue and persuade, to think and entertain, to talk and listen. But which one is the one, the seventh poet of a seventh poet, the one who can “make your heart feel glad,” “heal the sick and even raise the dead,” “make your flesh quiver”? You know when you meet the one who thinks they’re the one, but how do you know the one who is the one, “in the whole round world, the only one”?

I met the poet Calliope Michail at the Berfrois table. She has a book out, “Along Mosaic Roads,” (2018, 87 Press, UK). She also appears in Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book, in the form of an interview conducted by the inimitable Vlad Savich. Calliope is refreshingly fresh, able to speak of poetry in clear and concise terms. She gracefully dances around Vlad’s often idiosyncratic questions:

“I think it’s a coy dance with writing. You choose it and it chooses you, but sometimes the feelings aren’t mutual” (126).

She describes with clarity the writing process:

“I tend to see each poem as a pattern. This pattern consists of layers and links, connections to things in various realms – the personal, the political, the aesthetic, the literary, the linguistic and so on. For me, it’s more of a process that may begin with a line, a concept, or some other preoccupation, that then gets built on” (127).

“Along Mosaic Roads” contains five sections, each beginning with a threaded poem, “Standing in the Sun,” Roman numerals I through V following. There are 17 poems in all. The titles of the poems sound like those of classical music tone poems. The book is a movement through time and place and person. Again we find the theme of wandering, “Going.” I’ll be spending more time in Calliope’s book in a later post, after AWP19 and Portland returns to its normal weirdness.

I also met at the Berfrois table veteran poet Dorothy Chan, a 2014 finalist for the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship. Dorothy has a book just out, Revenge of the Asian Woman (Diode Editions, 2019). Dorothy is obviously a capable writer and speaker and advocate for poetry as a means toward understanding one’s place in popular culture and how to take control of a picture others may have of you (probably very different from the picture you have of yourself), as was evidenced in my brief conversation with her amid the distractions at the table, but also as evidenced in her essay written for Queen Mob’s Teahouse: Teh Book, “Asian Princesses: Fetishisation, Sexiness, Anime Girls and Poetry” (95).

“The very thing that makes you fetishised, such as ‘Asian girl cuteness’ or kawaii fashion can be turned on its head and become a thing of power” (101).

I’ll also be spending more time with “Revenge of the Asian Woman,” in a future post. The essay is erudite, but the theory behind it is very clearly explained.

“I wonder a lot about the way we command ourselves through how we dress, and how these thoughts can be translated to poetry, since fashion is poetry” (98).

April 1st, 2019

Wandering post AWP19 Portland town yesterday with entrepreneurial intrepid impresario Berfrois editor at large Russell Bennetts and his Midwestern sidekick Simon Calder, I had occasion to consider Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises” in a contemporary context, where all the characters have cell phones, except one, who has lost theirs. But I can’t decide which Hemingway character would be cellphoneless: Jake? Lady Brett Ashley? Certainly not Count Mippipopolous, whose Twitter feed at AWP19 would be going nonstop. Maybe we would have Jake’s friend Georgette find the lost cell phone, but she would keep it hidden for a time, posting miscreant tweets and pics with her bad teeth.

The idea behind Thornton Wilder’s “The Eighth Day” is that God, having created the world in 7 days, proceeds to take the 8th day off, during which what we now consider time takes place, such that we are all, since the beginning of time, living in the 8th day of creation.

After their holiday in Pamplona at the festival of the bulls and all the bullfighting, “The Sun Also Rises” characters go their separate ways, Robert Cohn disabused of his romanticism, Jake cemented in his existential crisis, Brett off with the once untouchable but now touched and wrecked bullfighter Romero. It’s going to be a long 8th day.

Diary crossposted with The Coming of the Toads.