Excerpt: 'The Eyelid' by S.D. Chrostowska

The months of spring saw a slew of attacks on wishful thinking and the creative imagination. Their authors skewered every ‘utopist’ and ‘visionary’ known to history, no matter their politics. They took an axe to cinema, the ‘dream factory,’ and to poetry, ‘the medium of prophecy,’ denouncing their practitioners as charlatans pulling wool over people’s eyes.

This genre of hatchet job was not new; oneirocriticism, already practised among the ancient Greeks and Islamic mystics, had become a fixture of intellectual life, under one name or another, in the nineteenth century. It had lost none of its popularity among modern reformists. But the extent to which the media had mainstreamed this brand of lettered butchery, and feasted on the meat of it, gave us cause for alarm. Constructive criticism of the ‘dream-lefties,’ the hated oneiro-gauchistes hostile to the status quo, was out of the question. The only acceptable way to comment now was damagingly and destructively. Another world was impossible. There were no alternatives. As long as you railed against the do-gooders and their air castles, or cried bloody murder while pointing to anarchists, naming names when necessary, you were guaranteed an avid audience.

I had been reading everything I could get my hands on of this literature to learn the language of the enemy (the maxim of she who had taught us, French schoolchildren, English). It was highly toxic writing, and, considering the nullity of its content, well executed. It called, in voices amplified with every iteration, in the dated idiom characteristic of these fanatical conservatives, for a new Prohibition. The cure for society’s woes was to kick for good the ‘opium of the masses.’ But the tenor of the metaphor was not, as in the days of Marx and Lenin, religion. It dug deeper, much deeper, and came up with…sleep.

Sleep was the source of all idleness; sleep was a drain on the economy; sleep induced illusions that competed with the demands and duties of reality; sleep enfeebled the will and was for the weak; sleep interfered with technical innovation, and with the swift completion of pressing public projects. In short, sleep was evil, and evil – sleep.

Bene dormit qui non sentit quam male dormiat: he sleeps well who feels not how ill he sleeps. Those for whom the few stolen minutes of slumber were a relief from oppression and the torture of overwork, and who were by no means a visible minority, had every right to feel threatened. The pamphlets denounced them as a ‘menace,’ ‘melancholics,’ ‘spaniels,’ ‘dog-faced,’ ‘bags of bones,’ and ‘canaille.’ I could have sat down and written the primer for this novel lingua imperii. Insomnia was no longer ‘voluntary’ but ‘recommended.’ ‘Closing one’s eyes’ became synonymous with ‘conspiracy.’

Such perversions of language by the professed ‘friends of the people’ were as rife as their spread seemed unstoppable. And, as anyone else who followed the discourse sedulously could have predicted, by midsummer, insomnia went from ‘recommended’ to ‘mandatory.’ It was to usher in a ‘great and full awakening’ – physical, moral, spiritual, and of the ‘dormant,’ untapped faculties – an eye-opening available to everyone like Holy Communion (the religious overtones clearly calculated).

To prevent interference with this universal illumination, sleeping under any pretext, on any occasion, was outlawed – all for the ‘greater good of society.’ Selling people on insomnia took such duplicitous slogans as One man who does not sleep makes two men, and two is always better than one. These ‘two-in-ones’ were mechanical, their bodies relieved of organic torpor. Bodies ruled by their organs were abject and wretched; bodies controlling their vital functions were godlike, and saw their powers multiply. The mind, no longer stultified by sleep, underwent fission, unlocking its unused capacity. A world peopled by savants awaited!

All ‘estates’ – not just the elites – would get ‘the boost,’ a new drug called Potium, to partake of this beatific state of high-functioning sleeplessness. Yet the social structure was to be no better for it. A new hierarchy emerged. On the bottom, there were the underdogs, as you might expect. Higher up, the ‘technicians’ enjoyed a self-evident utility. Above them, finally, sat the ‘specialists’ – measly technocrats with significant, publicly defined administrative duties. With this new nomenklatura came a new nomenclature. The Minister of Education became ‘Virtual Literacy Specialist.’ The Ministry of the Interior now went by ‘Specialty for the Maintenance of Public Order and Consciousness.’ And the top brass of the ruling ASP, Alternative Socialist Party, hid behind the superlative ‘Specialty of Specialties,’ with the Office of Prime Minister (that holy of holies) predictably retitled ‘Office of the Chief Specialist of Specialties.’

As for the ‘Specialist of Occupations,’ he scrapped the luxury of the thirty-five-hour workweek: the workers of the future could easily put in twenty hours per day, in several shifts, with breaks for three square meals. Downtime in any shape or form was frowned upon, and was on its way out. Freedom through work! Work liberates! – these mottoes were only vaguely familiar, and chanting them with an upbeat air was enough to make them contagious. Gainful employment was, of course, not guaranteed. Productivity, we were assured, did not need remuneration to ‘count’ in the eyes of ‘leaders of industry.’

Offenders against the system – a label earned for the smallest infraction – were punished with (unmedicated) sleep deprivation. The daily Potium fix was withheld from them.

Over the weeks in which these ‘final touches’ were rolled out by our ‘specialists without spirit’ – gradually and as inconspicuously as possible, such that they seemed just more of the same but kicked up a notch – I watched from the sidelines and could scarcely believe my eyes. Nor did having my sight intact help me see how what were, to all appearances, steps taken in the dark could end up where they did, somewhere so fantastically precise – unless, that is, they were steps on a well-worn path down the abyss of history.

The people, meanwhile, before being wolfed by the state, had no choice but to swallow such propaganda whole, half-knowing that the idea behind it was not their happiness and well-being, but, rather, their heartless exploitation.

‘At least they don’t all gobble it up. It still has to be forced down their throats,’ Chevauchet jeered half-heartedly, as though feeling sorry for his targets. ‘Some still manage to quack out orations on the dignity of man. You know things are bad when the last shred of hope is a quacking duck! Quack of a duck! Quack-quack!’

Those who got on board voluntarily, CI helped look the other way. But the worst by far – the deadest ducks of all – were the token ‘agitators,’ who blamed sloth and sleep for getting us into a Catch-22. Chevauchet foresaw a special place in hell for these ‘useful idiots.’ They were no better, and did more damage, than state apologists. ‘We weren’t vigilant enough,’ they cried. ‘We failed to sound the alarm to stop the seizure of power. But now we’ve been swung to the other extreme. This imposed wakefulness is our well-earned punishment. We didn’t act when we still could. Narcoleptic children of Palinurus, we fell asleep at the helm, thinking instead of acting. And we lost control of the ship. We were not conscious enough to steer it. We were not awake enough to think. And now we are too awake to dream,’ they scribbled, meekly sipping their daily dose of Potium.

Excerpted from The Eyelid, by S.D. Chrostowska, forthcoming from Coach House Books in April 2020. Published with permission of the author.

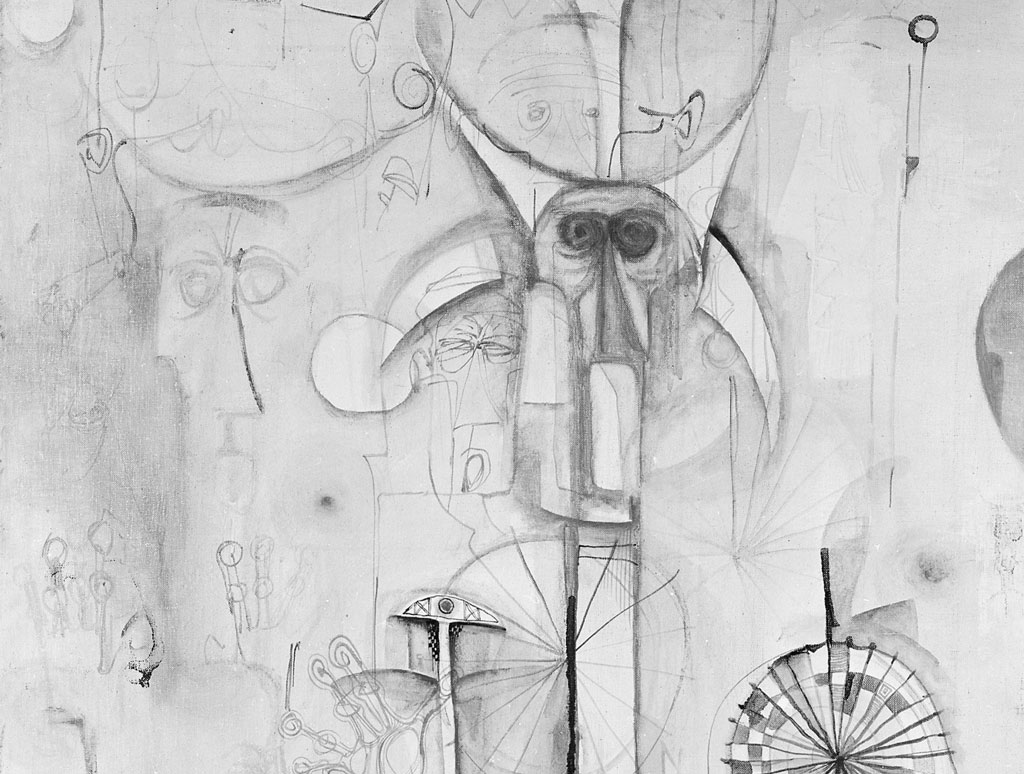

Image from The Donkey in my Dreams, author unknown, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration