Sleaford Mods as Ready-Made Art

by David Beer

All That Glue,

Sleaford Mods,

Rough Trade Records, 2020

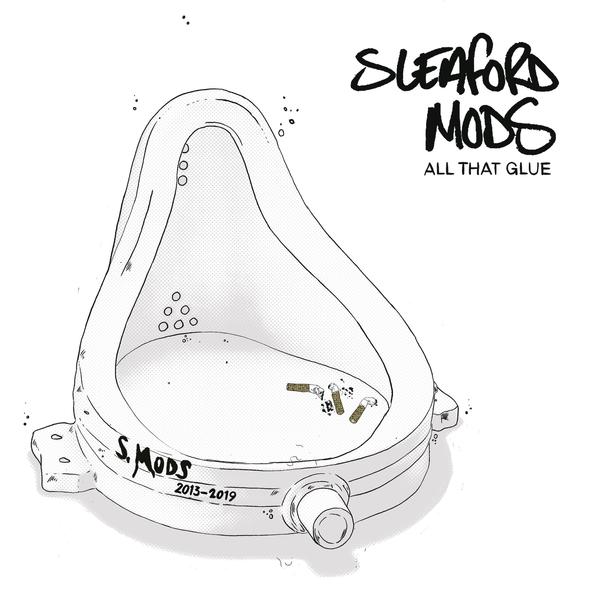

As the vinyl spins on my turntable, I’ve been pondering Sleaford Mods’ choice of sleeve design. An adapted version of Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Fountain adorns their new retrospective album All That Glue. As is well known, Fountain is simply a single urinal that was first hung on an exhibition wall in 1917. That urinal became foundational to the idea of ‘ready-made’ art and the notion that everyday objects can be transformed into artistic works. Where the original sculpture was signed “R.Mutt 1917,” this sleeve image simply has “S.Mods 2013-2019.” Throw in three cigarette ends and the update is complete. A great cover.

Speaking to its postmodern tendencies, the original Fountain was subsequently lost and replaced with a replica, yet the idea and imagery behind it have remained powerful. The statement it makes is clear: there is art to be found in ordinary things, if you know what to do with them. By placing the familiar into an unusual space it charges it with extra meaning.

As a suggestive and ambiguous piece of art, Duchamp’s Fountain was open to interpretation and inevitably divided opinion. Both of these things also apply to Sleaford Mods. The fact that this isn’t any old urinal on the cover would suggest that there are some other parallels going on. Maybe the Sleaford Mods see themselves as ready-made artist – picking up and then exhibiting the detritus and unglamorous aspects of modern life. The songs gathered here, such as the pulsing “Jobseeker”, are like urinals on a studio wall. As with that original sculpture, Sleaford Mods are exhibiting overlooked stuff whilst also challenging us to think about what music can be.

Maybe, probably, I’m reading too much into something that just worked as an image. It may just have been a design that fitted neatly with the sound. And I know that you aren’t really supposed to write about covers in reviews, but the contrast to their other albums got me thinking: perhaps we can think of Sleaford Mods as musical ready-made artists.

Andrew Fearn and Jason Williamson have been collaborating in this current incarnation of the band for around seven years. First finding a foothold by providing a kind of soundtrack to austerity Britain, their creative drive has led to a series of albums and EPs over recent years. The harshness of ongoing cuts and the untended wounds of inequality both informed their music, whilst also giving them a context to soundscape.

Another way to approach the music is through its lack of genre convention. The techno-grunge soundtrack to a twisted social scene doesn’t quite slot anywhere – like the urinal, it defies easy labelling. There’s hip-hop and punk in the mix, of course. Maybe some soul, post-punk and dub. I’m not sure that genre serves the music, and maybe that’s why they have been starting to find a crossover audience.

The music isn’t perfect, it has problems, but that’s part of the point. There’s plenty of polished music around – the rawness of Sleaford Mods is a crucial part of their sound. The artistic risks they take are part of what makes the music interesting and is also why it will occasionally fall flat. Stripping music back this far leaves nowhere to hide. Sleaford Mods music is so minimalist you can hear each component on the plate. Nothing gets drowned out or muddied.

The minimalism is brilliantly crafted but it sometimes creates its own problems, showing up where the material isn’t quite so strong. I’m not sure that the track “Blog Maggot” really works and the slowed down version of “No One’s Bothered” is some way off the quality of the original version. Elsewhere though, that trademark stripped-back sound is explosive and riveting. “Jobseeker” is the standout track, along with the instant “McFlurry”, the fatalistic rhythms of “BHS”, the biting “Snake It”, the mesmeric rolling beats of “Rich List” and others. Most of the 22 tracks keep the clutter low and the standards high. In other cases the sound expands and has more textures, not many more, but the dimensions start to open up – most clearly on the particularly delicate (by Sleaford Mods standards) closing track “When You Come Up To Me”. A crammed few years of creative energy means that All That Glue showcases the subtle divergences in Sleaford Mods music too. For music that is so stark, it is amazing how much is revealed by repeated listens.

Of course, there is anger and social observation in All That Glue, but the mistake would be to think that that’s all there is. There’s also something more relational in the visions. It mixes commentary and observation with flights of imagination and ambiguous phrasing. It’s not necessarily the full on realism that it first appears, it’s also a social psychology of modern experience that captures the thoughts and delusions that splinter from alienation.

Retrospectives are always about looking back, but they also suggest possible futures. Compilations of released and unreleased tracks, like this double LP, pose questions about what might come next. All That Glue feels like a line is being drawn on a productive period for the band. The closing tracks suggest that something slightly different is starting emerge, bringing a bit more of the soul tinge to the post-punk blend. Maybe a slightly more harmonious sound will come along, I doubt it though.

In pandemic times I’m picturing Fearn sat amongst his chaotic equipment, formulating a sinister and foreboding soundtrack. That picture of Fearn got me wondering what it would be like if Sleaford Mods produced an instrumental track, a kind of sonic interlude to the visions of life that Williamson is no doubt holed up scribbling into multipack spiral notepads. The commentary on the last seven years captured in these tracks leaves me guessing at what their music might say about the disruptions and distances of life as we are now living it.

In some interview or other Joe Strummer once described The Clash as a ‘news band’, or something along those lines. He was referring to how their music responded to what was going on in the world. Sleaford Mods aren’t a news band. I imagine The Clash’s influence is in there but All That Glue shows that they are doing something a little different. These tracks often feel more like a fraught internal dialogue spinning out of a claustrophobic setting. They are as much about the lived emotions and frustrations provoked by the state of things as they are a description of the politics of the times. Sleaford Mods are more like a ready-made band, putting the contortions of modern life on display. The band have said that they have no manifesto, but ripping out alienation and putting it on a wall is powerful in itself. As Williamson proclaims at the end of the track “Rich List”, ‘that’ll do’.

About the Author:

David Beer is Professor of Sociology at the University of York. His most recent book is The Quirks of Digital Culture.